In December 1904, two curious articles appeared in Indianapolis’ German-language daily, Indiana Tribüne (one of the many historic Hoosier newspapers digitized by NDNP).

Headlined “Peter Nissen und sein Ballonschiff”, the first small clip announces the disappearance of a remarkable Great Lakes daredevil and accountant, Chicago’s Peter “Bowser” Nissen, who had been in and out of American and international newspapers since 1900.

Nissen’s waterborne adventures by boat, “balloon ship”, and possibly even submarine are a strange tale, a confusing mix of fact and mixed-up news reportage. Eleven years after his tragic death in 1904, and in the wake of another Great Lakes maritime tragedy, the little-known daredevil steps into mystery and even folklore.

On December 1, 1904, Indianapolis’ German readers encountered news of the adventurer’s disappearance on Lake Michigan just a few days earlier:

Chicago, Nov. 30 – It is feared that Peter Nissen has either drowned or frozen in his rolling balloon, which he dubbed “Foolkiller” – a name that now seems to have been well chosen.

Nissen began his dangerous journey over the lake yesterday afternoon. No news has been had of him in 24 hours.

Nissen is the same daredevil who several years ago shot the rapids of Niagara Falls in a boat.

The assumption that Nissen has drowned grows more likely, since the only air supply at his disposal in the “Foolkiller” had already been depleted before he left the shore. Nissen encountered a gale which pummeled the lake with winds of 48 miles an hour.

In the same news clip, the Tribüne includes a report from South Haven, Michigan, on the lake’s eastern shore, that a search along “various points of the coast from Michigan City to Muskegon has returned no word of Nissen, who dared the open lake in his Foolkiller, a canvas boat with air-cushions. It is believed that Nissen has become a victim of his valor.”

The following day, December 2, the Tribüne brought a further report from Berrien County, Michigan:

[Stevensville, Mich., 1 December. Peter Nissen, who sought to traverse Lake Michigan in his balloon-boat, was found dead on the beach 2 ½ miles west of here today. It is thought that his body was washed up on the local beach during the night. The balloon was found about 20 rods away from him, in a very sorry state. The body was brought here, where it is being kept in the town hall. The hands and face were frozen and the lineaments of his face bore signs of infinite distress. The clothing was rather torn. The body was found by Mrs. Collier, who lives on a farm near the lakeshore.]

Who was this Peter Nissen, then, whose fantastic story the Tribüne barely digs into?

Born to Danish parents in Germany in 1862, Nissen was an immigrant himself. One report said that he lived in poverty in Chicago, where he worked as a bookkeeper. His death certificate issued in Michigan says that he was single and had worked as foreman in a furniture factory.

Nissen apparently first made national news headlines as early as 1900, when, at age 38, he successfully shot the Whirpool Rapids of the Niagara River in New York, just downstream from Niagara Falls. Many previous Niagara daredevils shot or swam the Rapids, often in wooden barrels, and almost always at the cost of their lives. Nissen’s was by far not the first attempt, but his was unique because of the strange boat he used to accomplish it.

Like the bizarre “balloon boat” he piloted to his death on Lake Michigan in 1904, this boat, too, was dubbed Foolkiller, and was actually one of at least three vessels Nissen called by that name. The feat was celebrated in papers as far away as his ancestral Denmark, where Skandinaven picked up the story on July 11, 1900. Probably translated from an American paper, this description of Nissen’s boat must have given Danish readers a picture of American bravado and the power of the American landscape. It also gives us some details about the mysterious vessel itself:

The boat used by Mr. Nissen for his dangerous feat is twenty feet long and four feet deep, built of pine with frame and keel of elm. In addition to the ordinary keel, the boat has an iron keel weighing 1,250 pounds, and the total weight of the boat is over two tons. There is a screw driven by foot power, and the boat has six airtight compartments, two in the bow, two in the stern, and one on each side.

A short clip in the Marshall County, Ind., Independent (July 20, 1900) reads:

Peter Nissen of Chicago, who prefers to be known as “Bowser”, made a successful journey through the Niagara rapids and whirlpool Monday afternoon in his boat, the Foolkiller. The boat struck the first foam-topped wave and turned over as easily as if it had been a stick and not a 1,250-pound keel. Man and boat disappeared. The watchers thought it was all over, when suddenly farther down stream “Bowser” reappeared, clutching the boat with one hand and waving his jersey cap with the other. The boat had righted itself. This occurred three times in the rapid journey, for it took only two and a half minutes for the whole trip through the rapids. Then “Bowser” and his boat were flung straight into the whirlpool. He was carried straight to the vortex which sucked in the boat, casting it up a minute later, with the drenched but plucky fellow clinging to its seat. Here it remained for forty minutes while the whirlpool played with it, spinning it like a top, then rolling it around the outer rims of the whirlpool. The man was finally rescued by three men who ventured into the water as far as they dared and caught a rope which he threw to them as his boat swung round on the outside of the pool. “Bowser” said the trip was more terrible than he feared, although he came out unharmed.

The first Foolkiller, then, was essentially a 1200-pound, foot-powered, deep-keeled kayak. In another section of the same issue of Marshall County’s Independent, Nissen’s craft is described as weighing

4,500 pounds, with a keel of iron which weighed 1,250 pounds. The keel acted like a pendulum and the boat was never wrong side up for more than five seconds at a time. The boat road the first wave like a duck. The second engulfed it and Nissen disappeared. He afterward stated that the wave nearly tore his head off.

To the eventual entertainment of many news readers, Nissen repeated his daring Niagara feat in 1901, in a restructured version of the boat, this time a longer, narrower craft featuring an eight-horsepower steam engine and a larger rudder.

The April 1902 Wide World Magazine includes several of the few photographs in existence of the second Foolkiller, hailing it as “The smallest decked steamer in the world,” a kind of steam-powered sea kayak. Containing himself in a small crawlspace beneath the cockpit, Nissen successfully shot Whirlpool Rapids for a second time in October 1901. An unknown cinematographer for the Thomas Edison Film Company even captured him in one of the earliest motion pictures. (The thrilling short is available on YouTube.) Unfortunately, on a third venture down the Niagara River late in 1901, Foolkiller II sank and was never seen again, probably ending up in Lake Ontario. Nissen and a colleague barely escaped drowning.

(Incidentally, Chicago’s accountant-daredevil wasn’t the only “fool” at Niagara Falls in October 1901. Just a week after his steam-powered Foolkiller II made it through the rapids intact, a Bay City, Michigan, schoolteacher named Annie Edson Taylor became the first person to go over Niagara Falls itself in a wooden barrel and live to tell the tale. Taylor did this on her 63rd birthday.)

With his second experimental vessel at the bottom of the Niagara River, Peter Nissen returned to the Midwest. By November 1904, he had pioneered his weirdest and wildest vessel, Foolkiller III.

A Popular Science Monthly article in September 1933 (“Freak Vehicles for Air, Land and Water”) regales readers with an account of Nissen’s final, fatal incarnation of the Foolkiller. The author claims that:

In the early years of the present century, Nissen was seeking a way to reach the North Pole. One of his schemes for traversing the rough Arctic ice was to use an automobile equipped with huge, low-pressure tires. Thus, thirty years before this time, Nissen dreamed of the modern balloon tire. Unfortunately for him, he didn’t stop there. The idea of the balloon tire kept growing in his mind. It got bigger and bigger and eventually the automobile disappeared from his plans and only the tire remained!

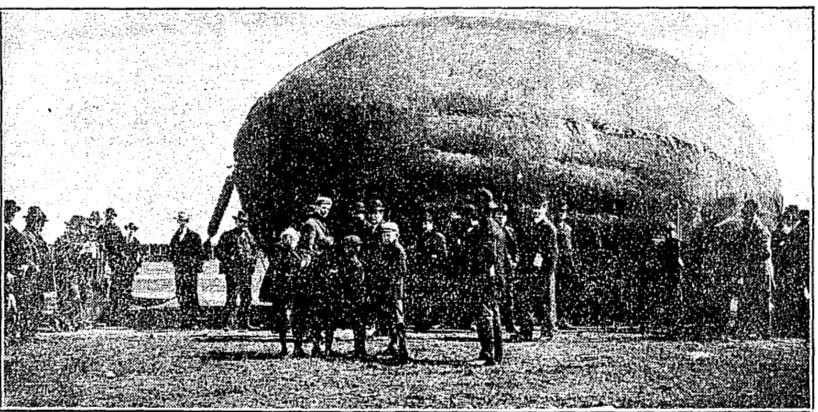

Nissen’s “fantastic scheme” was not unlike his previous experiment with turning a kayak into a steamboat. This time he would virtually turn a zeppelin into a ship. According to the Popular Science Monthly article, Nissen eventually intended to create a canvas bag 115 feet long and 75 feet in diameter. Filled with hydrogen gas, the balloon would sail north to the Arctic carrying the car underneath. After landing on the ice, Nissen would deflate the balloon and drive the car through a special door in the canvas. By means of a pump, the airtight “football” would reinflate once the car was inside. Nissen planned to string the automobile itself on cotton ropes hanging from a revolving interior wooden axle that stretched from end to end of the “football”. Air-tight glass portals allowed him to see out. Powered by winds, and with the ability to sail over both water and Arctic ice sheets, Nissen would literally roll to the North Pole.

Amazingly, in the summer and fall of 1904, Nissen actually constructed a miniature 32-foot-long version of this contraption and was performing test runs a few miles out on Lake Michigan, just off the Chicago shoreline. Photographs in the Chicago Daily News show the inventor at work next to his “pneumatic ball.” Readers of the Indiana Tribüne, the Indianapolis Journal and other papers might not have known the background to this story when they read about the “Der Foolkiller” on December 1, less than 48 hours after Nissen set out on his fateful voyage.

Reporters at the time claimed that he left from Chicago’s Navy Pier bound for Michigan City, Indiana. Caught in a gale (or did he deliberately go out in the gale to test Foolkiller’s ability to withstand bad weather?), Nissen may even have drifted within sight of Gary and the Indiana Dunes.

After his body was recovered on the beach just south of Benton Harbor, Michigan, doctors believed that Nissen had probably survived the gale itself, but either suffocated inside the balloon or drowned while trying to get out of the surf. A handwritten note found in the balloon suggests he knew he was going to suffocate. He may have died just offshore. (The South-Bend Tribune claims that the only provisions found inside the balloon were biscuits, cheese, tobacco, and water. The Indianapolis Journal claims that Nissen subsisted only on candy.)

Readers in Indiana and elsewhere who heard of the navigator’s terrible fate might have thought it an end to Foolkiller stories. But on November 25, 1915, eleven years later, the South Bend News-Times published this surprise item:

Chicago, Nov. 24 – Efforts were being made today to raise the “fool killer” submarine that has been buried in the mud of the Chicago River for 18 years. The diving boat was found by William M. Deneau, a diver, who was laying a cable in the river bed.

The boat was owned by Peter Nissen, an old time mariner. It was a cigar shaped craft, and could be submerged until an air pipe about 10 feet high was the only part that stuck out of the water. Nissen, who never succeeded in putting the subsea craft into practical operation, lost his life trying to drift across Lake Michigan in a revolving boat, another of his spectacular inventions.

Where this submarine came from is a mystery. As long ago as the 1840’s, a Michigan City, Indiana, shoemaker, Lodner D. Phillips, was actually building and patenting several unsuccessful submarines on the Great Lakes, all of which stayed on the bottom. (A fascinating article from the Ann Arbor Chronicle tells a bit of Phillips’ story.) Was this the wreck of a much older vessel? At a time when the Chicago River was being dramatically re-engineered for human use, it is hard to imagine how a submarine could have gone unnoticed under three feet of mud right in the heart of the downtown business district, next to the Wells Street Bridge, for so many years.

Yet as photographs from the Chicago Daily News attest, something was definitely pulled out of the river in 1915. (Interestingly, these photographs may have been taken by Jun Fujita, the first Japanese American photojournalist, who was employed by the Daily News.)

Chicagoans’ morbid interest in the discovery of the submarine (which the Daily News called “Foolkiller,” “something out of Jules Verne’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea”) was due in part to its proximity to the site where the SS Eastland capsized six months before, killing 844 passengers boarding a vessel for Michigan City, Indiana – the deadliest disaster in Chicago history. In a twist of fate, William “Frenchy” Deneau was one of the heroic divers who recovered about 250 bodies of Eastland victims from the river that summer. After the submarine turned up in December, there were tales that Deneau, its 23-year-old discoverer, had also found the bones of a man and dog inside — not the first such find on the bottom of the river.

To cap the story off, the Chicago submarine’s ultimate destination is as murky as its origin and sudden reappearance. Deneau reportedly got permission from the U.S. government to salvage the vessel. He put it on exhibition on State Street for several months, charging 10 cents admission, then sent it out on a tour of Midwestern county fairs. The bizarre vessel, it is thought, disappeared at a fair in Iowa in 1916. No trace of it turned up again.