Exactly 150 years ago today, Abraham Lincoln, who spent part of his rail-splitting boyhood in Spencer County in southern Indiana, fell victim to the bullet of the 26-year-old actor John Wilkes Booth at Ford’s Theater. Soon, the president’s body headed west by train, stopping in Richmond, Indiana, for a public viewing at 2:00 in the morning on April 30, then on to Indianapolis and Michigan City, with short stopovers at small Hoosier train stations along the way.

In a downpour, possibly fifty thousand Hoosiers viewed Lincoln’s open casket in the rotunda of the old State House. (At a time when the population of the capitol city was less than 40,000, the crowd of black-draped mourners must have been a spectacle in itself. Many were African Americans clutching copies of the Emancipation Proclamation.) Just before midnight, a carriage brought the president’s coffin through the rainy streets of Indianapolis, lit by torches and bonfires, to Union Depot, where it departed north by train for the south shore of Lake Michigan, en route to Chicago and eventually to Springfield, Illinois.

An exhibit running through July 7 at the Indiana State Museum, So Costly a Sacrifice: Lincoln and Loss, includes some actual “relics” of that fateful Good Friday in 1865 when Booth shot Indiana’s favorite son. Among the artifacts are a few that seem like medieval religious relics: clothing with spots alleged to be the blood of Honest Abe, and a piece of the burning barn in Port Royal, Virginia, where the assassin met his own fate at the hands of a Union soldier, the eccentric street-preacher Boston Corbett.

One of the most interesting things to me about the Lincoln assassination and the funeral that came after is the apparent curse on the people and even the physical things involved in it. Poe’s Raven could be telling the story, and the bird of death keeps on talking, quawking not “Nevermore” — just “More.”

What happened to Booth and Corbett is pretty bizarre and appalling. Basil Moxley, a doorman at Ford’s Theater who claimed that he served as one of Booth’s pallbearers in Baltimore in 1865, fed a conspiracy theory in 1903 when he asserted that another man is buried in the plot and that Lincoln’s murderer actually escaped to Oklahoma or Texas. A mummy hoax brought the assassin back to life as a sideshow attraction in the 1920s. But perhaps the moody English-American actor would have been thrilled to know that the morbid tragedy he let loose wasn’t over yet.

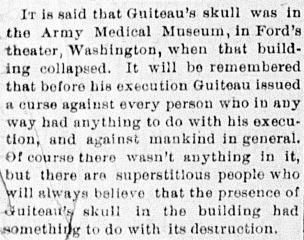

For instance, Booth’s own killer probably went down surrounded by flames. It is thought that Boston Corbett died in the massive forest fire that consumed Hinckley, Minnesota, in 1894. And oddly enough, the very train car that carried Lincoln’s corpse west to Illinois from Washington also burned in Minnesota. In March 1911, while in storage in the northeastern outskirts of Minneapolis, the historic Lincoln funeral car perished in a “spectacular prairie fire.”

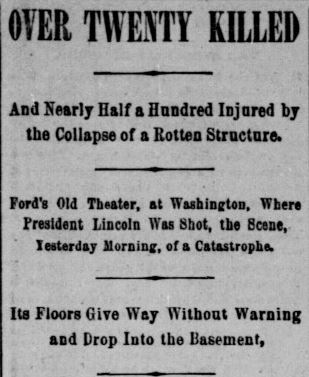

In 1893, a year before the inferno in the North Woods probably claimed Corbett’s life, news readers followed the ghastly story of Ford’s Theater’s own doom. On June 10, the Indianapolis Journal ran this especially sentimental, tear-jerking news piece on the front-page:

As the Journal tells it:

Hundreds of men carried down by the floors of a falling building which was notoriously insecure; human lives crushed out by tons of brick and iron and sent unheralded to the throne of their Maker; men by the score maimed and disfigured for life; happy families hurled into the depths of despair. . . Words cannot picture the awfulness of the accident. Its horrors will never be fully told. Its suddenness was almost the chief terror. . . Women who kissed their loved ones as they separated will have but the cold, bruised faces to kiss to-night. . . In the national capitol of the proudest nation on earth there has been a catastrophe unparalleled in the annals of history, and in every mind there is the horrible conviction that its genesis is to be found in the criminal negligence of a government too parsimonious to provide for the safety of its loyal servants by protecting its property for their accommodation.

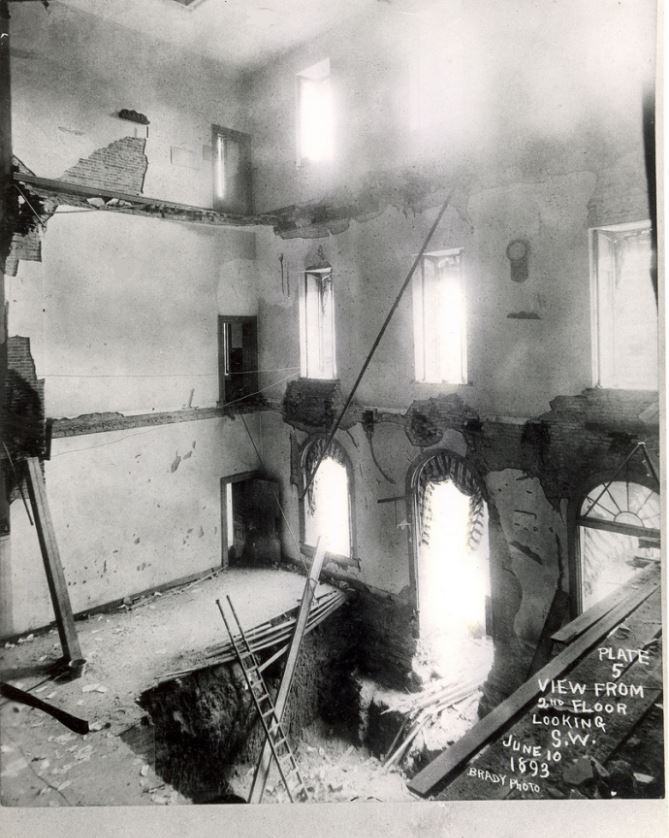

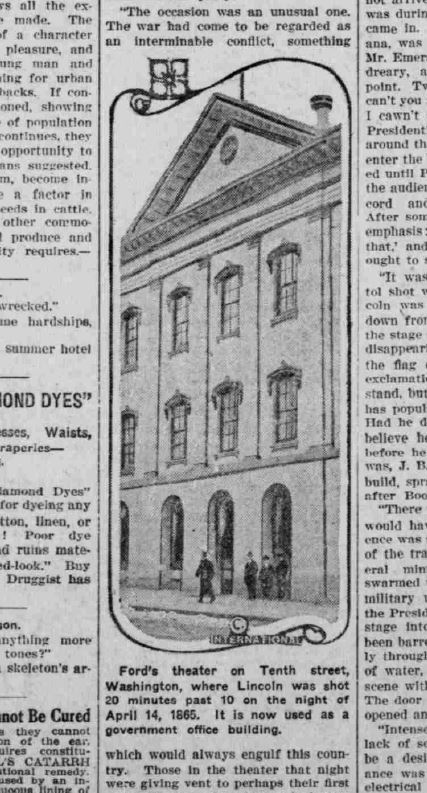

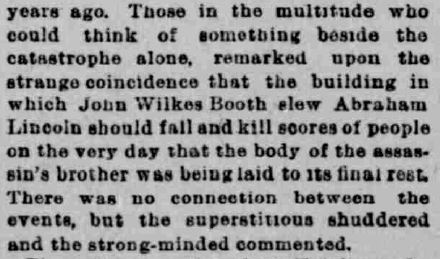

At 9:30 a.m. on June 9, the front part of Ford’s Theater, a notoriously rickety and rotten old structure then being used as a government office building, collapsed, sending beams, iron, and over a hundred employees plummeting toward the basement. Twenty-eight years after Abraham Lincoln was shot here, twenty-two men were killed and sixty-eight injured in one of the deadliest disasters in Washington, D.C.’s, history. (In a twist of irony, the same day the theater collapse made national headlines, John Wilkes Booth’s brother, the great American actor Edwin Booth, was laid to rest at the Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Many said that Edwin Booth’s life and death were overshadowed by two different tragedies and the curse of Ford’s Theater.)

Collapsing structures were a major news item in the 1890s. Almost every week, American papers reported mass casualties at overcrowded factories and apartment buildings, especially in Chicago and cities back on the East Coast, where poor construction and dry rot led to the deaths of thousands of industrial workers and tenants — often women and children. During the Progressive Era, such tragedies inspired reformers like the photographers Jacob Riis and Lewis Hine (who documented child workers in Indianapolis in 1908) to illustrate the real peril of shoddy, dilapidated buildings in the workplace and at home.

In 1893, Ford’s Theater was probably one of the most dangerous structures in America. Built in 1863 by the 34-year-old entrepreneur John T. Ford, the building occupied the site of a Baptist Church-turned-theater that had burned down a year earlier. John Ford’s business was a victim of Booth, too. After the Lincoln assassination, public opinion and the U.S. government both decided that it was inappropriate to use the site of the nation’s great tragedy for entertainment. Ford wanted to re-open his theater, but received arson threats from at least one Lincoln mourner. The Federal government appropriated the playhouse, compensating its owner with $88,000 in July 1866.

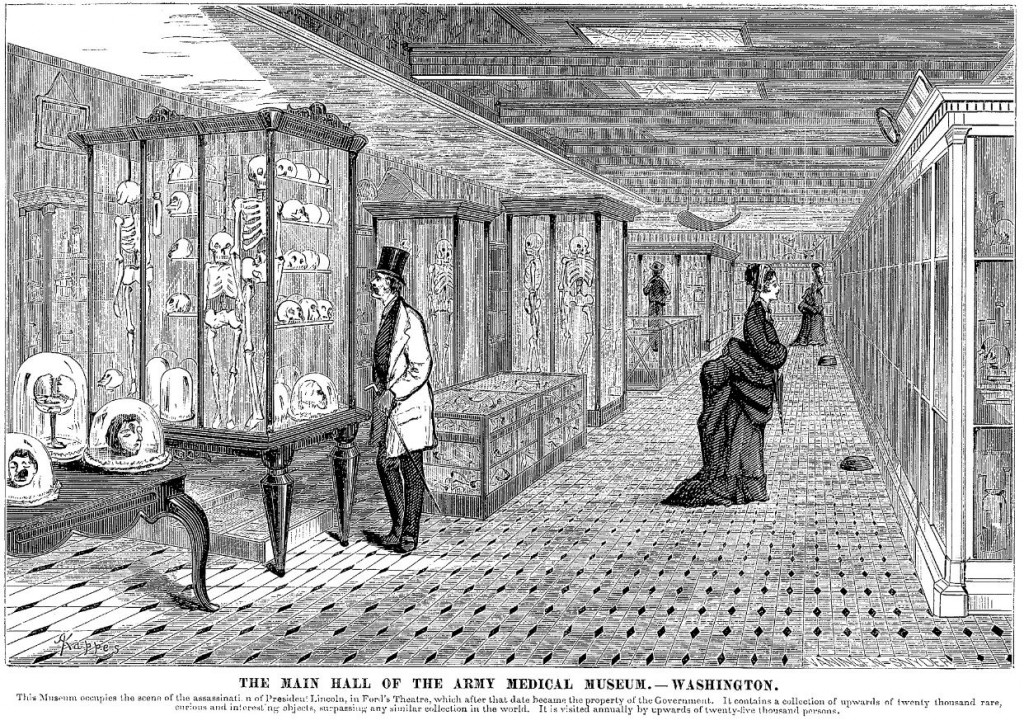

Even before the government actually paid for the building, renovations were underway. In December 1865, the suitably morbid Army Medical Museum moved onto the third floor. “A far cry from the once jovial theater,” the famous local landmark now housed an array of skeletons in glass cases, body parts, surgical tools, and other gory reminders of military medicine. The Library of the Surgeon General’s Office soon occupied the second floor.

The other floors of the former theater housed the War Department’s Office of Records and Pensions. The unstable, visibly bulging building was the workplace of several hundred employees and was further imperiled by probably a few tons of heavy paperwork, the red tape of veterans’ pensions.

After the building succumbed to gravity and rot in 1893, American public opinion was almost as outraged as at the assassination of Lincoln. The Indianapolis Journal wrote:

As long ago as 1885, this building. . . was officially proclaimed by Congress an unsafe depository for even the inanimate skeletons, mummies and books of the army medical museum, for which a safer place of storage was provided by an act of Congress. But notwithstanding the fact that in the public press, and in Congress, also, continued attention was called to the bulging walls of the building, its darkness and its general unsuitability and unsafety, it continued to be used for the daily employment of nearly five-hundred government clerks of the pension record division of the War Office.

According to a riveting coroner’s inquest that whipped up public excitement, workers at what the Indianapolis Journal dubbed “Ford’s death trap” had been intimidated and cowed into silence by their tyrannical boss, former army surgeon Col. Fred Ainsworth. Afraid of being fired, the endangered clerks didn’t protest the condition of the building and later testified that Ainsworth’s assistants had told them to tip-toe on the stairway to keep from falling through. Investigators determined that the “old ruin’s” collapse finally came while a low-bidding contractor, George W. Dant, was making repairs to the building. (A support in the basement gave way.)

Court testimony relayed in the Journal resonated with public opinion. “The government did not want skilled men to execute its contracts, and it would not pay fair prices for good work. . .” the paper claimed. “An architect testified that the cement used in underpinning the piers supporting the old building was ‘little better than mud.’ A builder said the manner of the work was suicidal.” Another report said that for years the decaying structure also suffered from “defective sanitary conditions.”

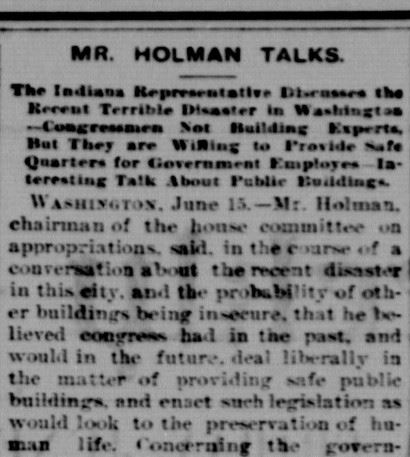

One of the public figures who weighed in on the federal investigation was Indiana Congressman William S. Holman. A Dearborn County native, Holman sat in Congress from 1859 to 1897 and was once ranked as the longest-serving U.S. Representative. He was also a notoriously frugal hawk on government spending. (Yet far from being a total naysayer, Holman passionately advocated the Homestead Act that tried to break up the domination of Western public lands by big railroads. He also indirectly helped establish the U.S. Forest Service by providing for Federal timber reserves.)

As chairman of the House Committee on Appropriations, the curmudgeonly Holman oversaw a lot of government funding. On June 23, 1893, the Jasper Weekly Courier reported that after Ford’s Theater collapsed, even the arch-fiscal conservative was ready to “deal liberally in the matter of providing safe public buildings, and enact such legislation as would look to the preservation of human life.” The Indiana Congressman supported moving the U.S. Government Printing Office — ranked with the old theater as one of the worst potential death traps in Washington, D.C. — to a new location. (The weight of printing equipment housed on upper stories was part of the problem.)

Yet once it was rebuilt after the 1893 collapse, Ford’s Theater returned to government use — oddly enough, as a storage warehouse for the Government Printing Office. The building narrowly survived being condemned for demolition by President Taft in 1912. From 1931 until renovations in the mid-1960s, the historic structure housed a government annex and a first-floor Lincoln museum. Restored to its 1865 appearance and now run by the National Park Service, it opened as a public museum in 1968.

Contact: staylor336 [AT] gmail.com