In 1858, Terre Haute, Indiana, was beginning to have an odd distinction: bite victims from all over the Midwest were coming here for a cure.

That year, Isaac M. Brown, editor of the Terre Haute Daily Union, suggested to the city council that the town purchase for public use a “madstone,” a curious leech-like hair ball found in the guts of deer — preferably an albino buck.

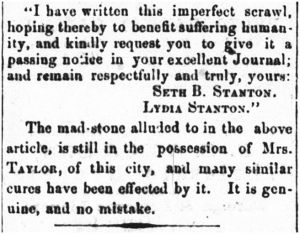

For centuries, folk doctors on both sides of the Atlantic believed such madstones to be helpful in warding off rabies infections and healing poisonous bites. (Queen Elizabeth I of England apparently kept a madstone hanging around her neck.) To back up his support for this public health measure in Terre Haute, Brown quoted a letter from the Mount Pleasant Journal in Iowa, which tells the wild story of one settler there, Seth Stanton, bitten by a rabid feline at his home near the Missouri state line.

On the morning of the 15th of March last I arose early, walked out to the gate in front of my house where I was attacked by a mad animal — a mad cat. It sprang upon me with all the ferocity of a tiger, biting me on both ankles, taking a piece entirely out of my left ankle, clothing flesh and all. [Perhaps it was a wildcat, not a domestic creature. Stanton is not specific.] I saw at once my hopeless condition, for the glairing eyes of the cat told me at once that it was in a fit of hydrophobia. I at once resolved to start forthwith to Terre-Haute, Ind., expecting there to find a mad stone. Accordingly in a few hours, myself and wife were under way, crowding all sail for that port.

Though rabies can take as much as a year to incubate and show any of its awful signs, Stanton wasted no time in traveling by train or river boat back east to Indiana. But when he discovered there was a madstone seventeen miles from Alton, Illinois, just across the Mississippi from St. Louis, he stopped there. Eight days after he was bitten, he wrote, “My leg turned spotted as a leopard to my body, of a dark green color, with twitching of the nerves.”

[I] drank no water for eight days. The stone was promptly applied to the wounds. It stuck fast as a leech until gorged with poison, when it fell off volunteerly [sic]. It was then cleaned with sweet milk, salt and water, and was applied again, and so on, for seven rounds, drawing hard each time, when it refused to take hold any more. — The bad symptoms then all left me, and the cure was complete, and I returned to my family and friends with a heart all overflowing with thanksgiving and praises to God for His goodness and mercy in thus snatching me from the very jaws of death.

American medical history is full of strange tales and oddball personalities. In some cases, medicine and folklore come together.

Though my family has lived in Terre Haute since the mid-1800s, I certainly had never heard anything about a famous “madstone” there. The “Terre Haute madstone,” however, shows up over several decades in American and even Canadian newspapers. At one time, journalists made Terre Haute out to be a virtual “madstone” mecca.

Madstones definitely weren’t Blarney Stones, and people who came looking for them weren’t tourists. Madstones, it turns out, weren’t even rocks at all. Once used as part of a rare but geographically widespread folk medical practice, they are also termed bezoars in both folklore and medical science. Categorized according to the type of material that causes their formation — usually milk, seeds, or plants mixed with an animal’s own hair from licking itself — bezoars are calcareous masses found in the gastrointestinal tracts of deer, sheep, goats, horses and even walruses. In folk usage, these masses were mistaken for actual stones, sometimes polished to look like beautiful grey hen’s eggs, and often thought to have nearly-miraculous properties.

Frontiersmen believed that when applied to the bite of a rabid animal, and in some cases even that of a poisonous snake, madstones could draw out the rabies virus or poison before the tell-tale symptoms set in. Rabies is almost always fatal and one of the worst ways to die. Victims of the infection will suffer from extreme, deathbed-splintering spasms as the virus wreaks havoc on the nervous system. Hydrophobia, characterized by frothing at the mouth and intense fear of water, follows from the inability to swallow. According to Dr. Charles E. Davis in The International Traveler’s Guide to Avoiding Infections, the World Health Organization knows of only one case of a human with rabies escaping an excruciating death once the virus reached the brain.

While the madstone has been thoroughly debunked, one can hardly fault the practitioners of early madstone “medicine” for giving it a go. In some parts of America, use of these stones lingered on into the 1940s.

One of the better pieces of writing about American madstones appeared in the Summer 1983 issue of Bittersweet, a magazine published by high-school students in Lebanon, Missouri. Called the “Foxfire of the Ozarks,” Bittersweet was a spin-off of the hugely popular books written by students in Georgia in the early 1970s. Based on interviews with Appalachian and Ozark old-timers, Foxfire and Bittersweet were a major spur to the countercultural back-to-the-land movement that came about during the days of the Vietnam War.

In “Madstone: Truth or Myth?” student Dena Myers looked at the old folk belief, once common far outside the Ozarks. She tapped into a vast repertory of tales claiming the stone’s effectiveness.

Drawing on interviews, Myers describes the actual use of the madstone:

People using the madstone for treatment boil the stone in sweet milk, or sometimes alcohol. While still hot, they apply the madstone to the wound. If the victim has rabies, the stone will stick to the wound and draw out the poison. Once the stone adheres to the wound, it cannot be pulled off. After the stone is filled with the poison, it drops off by itself. It is then boiled again in the milk which turns green the second time. The process of boiling and applying is repeated until the stone no longer sticks to the wound.

French scientist Louis Pasteur pioneered a rabies vaccine in the 1880s, but its side-effects were so terrible that many people avoided it. (“Some Ozarkians say they would rather use the madstone than take the shots,” Myers wrote.) References to a “Pasteur treatment” or “cure” at the turn of the century are misleading. Once symptoms appear, “treatment” for rabies can do little but lessen the agony of death. Those who “recovered” from rabies after a madstone treatment never had it to begin with.

Fred Gipson’s novel Old Yeller, set in the Texas Hill Country around the time Pasteur was working on the first rabies vaccine, captures the real tragedy of the disease, which was common before vaccines, muzzling and the “destroying” of animals brought it under control in developed countries. In the U.S. today, rabies rarely occurs in dogs and cats, but still occasionally shows up in bats, who transfer it to livestock, pets, and humans, often un-vaccinated spelunkers.

Belief in a madstone remedy for rabies goes back centuries. (Bezoar, in fact, is based on a Persian word, and use of the stone was recommended in Arabic medical manuals in medieval Spain.) Scottish settlers seem to have been mostly responsible for bringing it to the American South, where they met American Indians who also used the rare stones. (A madstone owned by the Fredd family in Virginia allegedly came from Scotland and was mentioned by Sir Walter Scott in his novel The Talisman.)

The Cajuns in Louisiana practiced madstone healings. (Many Cajun folk beliefs came from African Americans and American Indians also inhabiting the bayous.) A stone yanked from the gut of an 18th-century Russian elk ended up in Vernon County, Missouri, on the Kansas state line, sometime before 1899. A madstone used in St. Francis County, Arkansas, in 1913 was dug out of an ancient Indian burial mound.

One of the first European practitioners of madstone healing in Indiana was John McCoy, an early settler of Clark County.

In 1803, McCoy married Jane Collins (known as “Jincy” McCoy) in Shelby County, Kentucky, just east of Louisville. As a wedding gift, or maybe as part of her dowry, Jincy’s family gave her a madstone in preparation for the couples’ move into the dangerous Indiana wilderness. It was “the best insurance they could offer against hydrophobia.” These are the words of Elizabeth Hayward, who edited John McCoy’s diary in 1948. “In giving their daughter the only remedy then known,” Hayward wrote, “the Collins gave her the best gift in their power as well as a rare one.”

John McCoy is best known for leading the Charlestown militia after the Shawnee attack on settlers at Pigeon Roost in 1812, one of the bloodiest events in Indiana history, which happened near his home. (Ironically, McCoy was the brother of the Rev. Isaac McCoy, a Baptist missionary and land rights advocate for the Potawatomi and Miami. When they were evicted from Indiana in 1838, Rev. McCoy accompanied them to Kansas and Oklahoma.) A deacon in the Baptist Church himself, John McCoy helped found Franklin College at a time when “Baptists were actively opposed” to higher learning, Hayward wrote. What is less well known is his battle against rabies in southern Indiana.

McCoy kept a laconic record of his days. On at least ten occasions recorded in his diary, he was called on to apply his wife Jincy’s madstone to victims of animal bites.

Hayward believes the McCoy madstone might have been the only one in that corner of Indiana at the time. True to a common superstition about proper use of the stone, McCoy “never refused [when asked to use it] and never accepted payment, apparently regarding the possession of the rarity as a trust. The victims were boys and men. Probably the circumscribed lives led by the women of his times, centered on their homes, kept them out of reach of stray animals. And more probably still, the voluminous skirts they wore protected their ankles from being nipped.”

McCoy applied the stone, carried up from Kentucky, long after Clark County, Indiana, had ceased to be a frontier zone. Most of his diary entries related to its use date from the 1840s.

April 9 [1844]. Sunday. At sunrise attended prayer meeting. At 11 attended preaching, afternoon detained from church by having to apply the Madstone to a little boy, bitten the day before. At night attended worship, then again attended to the case of the little boy till after 12 o’clock.

Later 19th-century medical investigation into the efficacy of the madstone suggested that while the stone did not actually suck out any of the rabies virus, it acted according to the “placebo effect” (i.e., belief in the cure itself allayed the bite-victim’s mind, which resulted in improvement — provided, of course, that there was not actually any rabies there.)

Yet around the same time John McCoy was practicing his primitive form of medicine near Louisville, Terre Haute was becoming a top destination for those seeking treatment — or at least reassurance.

Mary E. Taylor, almost always referred to in newspapers as “Mrs. Taylor” or “the widow Taylor,” was the owner of the famous “Terre Haute madstone” mentioned in many American newspapers. Her stone’s virus-sucking powers were sought out from possibly the 1840s until as late as 1932.

Local historian Mike McCormick believes that Mrs. Taylor was born Mary E. Murphy, probably in Kentucky. Marriage records show that a Mary E. Murphy wed a Stephen H. Taylor (no relation to the author of this post) in Vigo County in April 1837. An article in the Prairie Farmer of Chicago mentions that she lived at 530 N. Ninth St. (This made her a neighbor of Eugene Debs.)

In 1889, Mrs. Taylor spoke about the provenance of her madstone to a reporter. “My mother’s brother had it in Virginia,” she told the Terre Haute Saturday Evening Mail, “and as he had no children gave it to my mother. That is as far back in its history as I can go.” An 1858 letter from Mary “I.” Taylor (possibly a misprint) appeared in the Evansville Daily Journal. She claimed the stone had been in use “for the past thirty years” in Vigo and Sullivan counties. The Terre Haute Weekly Express claimed the madstone came to Indiana via Kentucky, after the Murphys lived there for a while in their move west.

Though Mrs. Taylor might have been widowed as early as the 1840s, hoax-busters who would suggest that she used her family’s madstone to support herself should remember the prominent superstition that warned against accepting payment.

A “widow lady” whom McCormick thinks was Mary Taylor “cured three cases” of hydrophobia in early 1848, according to the Wabash Express.

During the decades when John McCoy and Mrs. Taylor were folk medical practitioners in the Hoosier State, Abraham Lincoln, according to an old claim, brought his son Robert to Terre Haute to be cured of an ominous dog-bite.

Poet and Lincoln biographer Edgar Lee Masters reported this claim in his 1931 Lincoln the Man. (Like the president, Masters was obsessed with melancholy and death. He grew up near Lincoln’s New Salem in Illinois and later set his paranormal masterpiece, Spoon River Anthology, in the old Petersburg cemetery where Lincoln’s first lover, Ann Rutledge, a typhus victim, lies.)

“He believed in the madstone,” Masters wrote, in a section on Lincoln’s superstition, “and one of his sisters-in-law related that Lincoln took one of his boys to Terre Haute, Indiana, to have the stone applied to a wound inflicted by a dog on the boy.”

Max Ehrmann, a once-renowned poet and philosopher who lived in Terre Haute, investigated Masters’ claim in 1936. At the famous hotel called the Terre Haute House, Ehrmann had once heard a similar story from three of Lincoln’s political acquaintances. They told Ehrmann that sometime in the 1850s, Lincoln, then still a lawyer in Springfield, brought Robert to Indiana for a madstone cure. Father and son stayed at The Prairie House at 7th and Wabash, an earlier incarnation of the famous hotel. A sister of Mary Todd Lincoln, Frances Todd Wallace, backed up the story.

“I have never been able to discover who owned the mad-stone,” Ehrmann wrote. “It was a woman, so the story runs.” If true, Robert (the only child of Abraham and Mary Lincoln to survive to adulthood) would have been a young child or teenager. He lived to be 82.

Mrs. Taylor’s “Murphy madstone” was probably just one of three such stones in Terre Haute that offered a rabies cure. Another was owned by Rev. Samuel K. Sparks, and Mary E. Piper’s “Piper madstone” was used until at least 1901.

Though her stone became nationally famous, Mrs. Taylor faced a healthy amount of skepticism. On March 6, 1867, the Weekly Express reprinted this clip from the Indianapolis Herald: “We understand that Mrs. Taylor, of Terre Haute, applied her mad stone to Mr. Pope, who died a few days since of hydrophobia. As it was not applied until after the disease manifested itself, it failed. We fancy, however, it would have failed anyhow.” Herald editor George C. Harding had inadvertently taken a swipe at Terre Haute, which was increasingly proud of Taylor’s madstone. The snub caused the editor of the Weekly Express, Charles Cruft, to retort:

We know it is wicked to do so, but we almost wish our friend Harding would receive a good dog bite, in order that his skepticism as to the efficacy of our madstone might be cured. Although he may have more faith in whisky, which is said to be an antidote for some poisons, we’ll bet the first train would convey him in the direction of Mrs. Taylor’s residence.

A mad dog bit four children in Rush County, Indiana, in March 1889. Their parents brought them to Terre Haute to see Mrs. Taylor. The Montreal Herald in Canada picked up the story. “The Terre Haute madstone has just completed the most thorough test ever given it. . . [Mrs. Taylor] remembers that it was handed down to her from her Kentucky ancestors. . . Physicians and scientifically inclined citizens have overrun her home here since the mad dog scare began in this state, and there is hardly a day that a patient is not brought to her.” A few days afterwards, two Warren County farmers came, “each being apprehensive that some of the saliva of a hog got under the skin of their fingers.”

A dog bit two children in Sugar Creek Township in 1892. The child brought to see Mrs. Taylor survived. As for the other, “death relieved her sufferings.”

In 1887, the madstone even ranked among Terre Haute’s “sources of pride.” While singing the praises of a local masonic lodge, the Saturday Evening Mail wrote: “[The lodge] deserves to rank with the Polytechnic, Normal, artesian well, Rose Orphan Home, madstone and Trotting Association.” On April 23, the newspaper added: “Someone has written the old, old story about the Georgia stone. The Terre Haute charmer’s turn will come along soon.”

Though papers reported other Hoosier madstones, like the “Bundy madstone” in New Castle (which stuck to a severely infected woman’s arm for 180 hours in 1903), Terre Haute’s fame spread to faraway Louisiana and Minnesota. But Mrs. Taylor’s cure sometimes disappointed. During the “dog days” of summer (an abbreviation of the “mad dog days” when a higher number of rabies cases usually occurred), the Minneapolis Journal ran this story in 1906:

Terre Haute, Ind., August 18 — William Painter, a farmer, died of hydrophobia from a cat bite, and in a moment of consciousness before the final convulsion, caused his attendants to tie him in the bed for fear he would do someone harm in his struggles. The death convulsion was so strong that he tore the bed in pieces, but no one was hurt.

He was bitten June 21 by a cat which had been bitten by a dog eight days before. He called the cat to him and as it sprang at his throat he caught it and was bitten in the thumb. He had the Terre Haute madstone applied, and as it did not adhere he felt that he was not infected with the virus.

A boy who lived east of Bloomington suffered a similar fate in 1890. Bitten by a dog while working in Greene County, 19-year-old Malcolm Lambkins went to Terre Haute to have the madstone applied to his leg, but it didn’t adhere. Though the wound healed, a short time later “the boy took sick, and when he attempted to take a drink of water he went into convulsions. He grew steadily worse and wanted to fight those about him, showing almost inhuman power.” Lambkin died on July 6. “An experienced physician states that he never witnessed death come in such terrible agony.”

Skeptics and scientists, of course, eventually established that saliva is what carries the rabies virus, and that if bitten through clothing, one was far less likely to be infected than if bitten directly on the skin. Also, not all animals thought to be rabid actually were. The mental relief of receiving the “cure” from the likes of Mrs. Taylor probably helped the healing of non-rabid wounds and infections by calming the mind, thereby boosting the immune system. (What the green stuff was that came out of the madstones, I have no idea.) Though mention has been made of bite-victims having recourse to madstones as late as the 1940s, they practically drop out of the newspapers around 1910.

One last appearance of the madstone in the annals of Hoosier journalism deserves mention. Scientists were justifiably proud of the anti-rabies vaccine, grown in rabbits, that gradually all but wiped out the virus in North America. But in 1907, even the so-called “Pasteur treatment” hadn’t come to Indiana. Just as today we sometimes talk jokingly about “those barbaric Europeans” who enjoy their free medical care, in April 1907 an anonymous doctor wrote this remarkable passage in the monthly bulletin of the Indiana State Board of Health. His (or perhaps her) racism was hopefully tongue-in-cheek:

The Pasteur treatment is the only one for rabies. “Mad stones” are pure folly. Faith in such things does not belong to this century. If a person is bitten by a dog known to be mad we urge such to immediately go to take the Pasteur treatment at Chicago or Ann Arbor. Indiana has no Pasteur Institute, and this reminds us of the admirably equipped and well conducted institute in Mexico City. In the land of the “Greaser,” unlike enlightened and superior Indiana, any person bitten by a mad dog can have scientific treatment for the asking. It is to be hoped that the State having “the best school system” will some day catch up with “the Greasers” in respect to having a free public Pasteur Institute.

Contact: staylor336 [at] gmail.com