You can thank Jonathan Jennings for making the Hoosier State a Great Lakes State two-hundred years ago, when he got Congress to nudge the border with Michigan a few miles north. But even with our gorgeous sand dunes stretched out under the shadow of the steel mills, Indiana hardly jumps to mind when it comes to maritime history.

That didn’t stop me from fishing for some home-grown Hoosier connections to the Life Aquatic. (Did you know that even far-inland parts of the state, like Leavenworth down on the Ohio River, once had thriving boatbuilding enterprises, with craftsmen turning out graceful wooden skiffs shipped around the U.S.?)

One of Indiana’s surprising links to the sea was Professor Henri Marion, whose obituary ran in the South Bend News-Times on August 15, 1913.

Marion was born in Tours, France, in 1857, and emigrated with his wife Jeanne Marie to America around 1883, when the couple were still in their twenties. The Marions lived briefly in Charleston, South Carolina, where their son Paul Henry Marion, who later served in the Navy, was born in 1884. In 1886, Henri Marion was a language teacher at the Norwood Institute on Massachusetts Avenue in Washington, D.C. An ad for the school listed him as a graduate of the prestigious Sorbonne in Paris.

By 1891, though, Marion had become a French professor at the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland.

An esteemed instructor there, Henri Marion may have been involved in the early use of the phonograph in teaching languages to naval cadets. Curiously, the French professor also got involved in another “linguistic” innovation involving technology — not “pidgin” English, but another kind of “pigeon” entirely.

(A pigeon-cote on the armored cruiser Constellation around 1894.)

The instructor was at the forefront of a U.S. Navy effort to improve the sending of messages via homing pigeon. An issue of Outing in October 1894 has this to say about it:

The military use of messenger pigeons has grown up since the Franco-Prussian war, when pigeons were first extensively used during the siege of Paris. In France, Germany, Austria, Italy, Spain and Portugal, the organization of military pigeon posts is now very complete, some of the nations owning upwards of six-hundred thousand birds. As homing pigeons are of no use as bearers of messages except after long and careful training, a service of messenger pigeons for naval or military use could not be improvised at short notice.

The United States messenger pigeon service has now been in existence for three years, under the charge of Prof. Henri Marion, United States Naval Academy, who has frequently urged that a permanent service be established along the Atlantic coast, from Portland, Maine, to Galveston, Texas. . .

In peace, the birds would be useful in giving notice of wrecks, fire at sea, lack of food, water or coal, or of any accident to vessels or machinery, if happening near the coast, and could frequently relieve the anxiety of friends of passengers on vessels overdue. . . When in October 1883 a light-ship broke from her moorings twenty-two miles from Tornung, off the mouth of the Eider, four pigeons were liberated from the ship and brought the news in fifty-eight minutes.

In 1896, Professor Marion filed a patent for a new watertight aluminum message holder that would be attached to the bird’s legs. Scientific American reported that Marion’s improved “quill” weighed “less than eight grains” and can “be fastened to the pigeon in an instant.”

(Marion’s patent for a message holder, October 1896.)

Around 1905, before he began spending his summers as a language teacher in northern Indiana, Henri Marion got involved with another strange naval odyssey: the discovery of the remains of John Paul Jones.

The Scottish-born Revolutionary War hero was most famous for captaining the Bonhomme Richard in a famous battle against the British vessel Serapis, fought off Flamborough Head in Yorkshire in 1779. Though hailed as the “Father of the U.S. Navy,” John Paul Jones fell from grace and entered the service of Catherine the Great’s Russian Navy in 1787, battling the Turks on the Black Sea, then wandered around Poland and Sweden, desperately looking for a country to serve. Jones ended up in Paris in 1790 in the early days of the French Revolution. Sick and miserably lonely, the 45-year-old hero died of a kidney ailment at his apartment in Paris in 1792. One of the captain’s few friends found him dead, kneeling face-down at the edge of his bed, apparently in prayer before his spirit took flight (or set sail?)

Thinking (wrongly) that the U.S. government would be interested in repatriating the hero’s remains for an honorable burial in America, a French admirer sought to preserve his body, even as the American ambassador, Gouverneur Morris, refused to help give Jones a proper burial in Paris. (“I had no right to spend money on such follies,” Morris wrote.) Like his contemporary Mozart, who was chucked into a mass grave in Vienna just six months earlier, only a few servants and friends attended Jones’ burial in the St. Louis Cemetery, which was set aside for “foreign Protestants.” The body was stuck in a lead-lined coffin filled with alcohol to aid preservation in case the American government ever ordered an exhumation. Just a few weeks later, after 600 Swiss Guards died defending King Louis XVI at his palace and were tossed in a mass grave next to Jones’ new coffin, the exact site of his burial became more and more mysterious.

The horrible burying ground later became a garden, then a refuse dump covered by a midden full of animal bones and kitchen waste. According to rumor, the neighbors held cock fights and dog fights at the site of the forgotten cemetery where America’s greatest naval hero lay. Over the course of the 1800s, a grocery store, laundry, and apartment house had also been built on top of it.

In 1899, General Horace Porter, U.S. Ambassador to France from 1897 to 1905, began an amazing six-year search for Jones that culminated in the discovery, photography, and repatriation of his remains. (I won’t spoil your lunch by posting the photos here, but I’ll just say he looks like King Tut. You can see them here.)

Professor Henri Marion — of homing-pigeon fame — was Ambassador Porter’s interpreter in France. Marion helped translate old documents and went on the archaeological digs that led to the discovery of John Paul Jones’ coffin. Porter’s team battled worms, stench, and fetid water along the way. His interpreter later wrote the definitive account of this search through subterranean Paris, a book published in 1906 as John Paul Jones’ Last Cruise and Final Resting Place at the United States Naval Academy.

Henri Marion accompanied the Revolutionary War hero as he sailed on his “final cruise” to Annapolis, Maryland, departing from Cherbourg, France, in July 1905, after lavish services at the American Church in Paris. A 13-day crossing brought Jones “home” to a ceremony presided over by President Theodore Roosevelt. Jones’ bones were then laid to rest in a temporary vault at the Naval Academy on the shores of Chesapeake Bay.

(The coffin of John Paul Jones is lowered to the deck of the USS Standish off Annapolis Roads, July 23, 1905. U.S. Naval Historical Center.)

Within a summer or two, the French interpreter who was so instrumental in the hunt for Captain Jones was in Marshall County, Indiana. By about 1907, Henri Marion was serving as a French and Spanish instructor at the Culver Military Academy’s Summer Naval School, a preparatory program for teenagers interested in enrolling in the U.S. Navy.

Founded on the shores of Lake Maxinkuckee in 1894, the Culver Academy began its unique summer naval program, hailed as “the only naval school west of the Atlantic Coast,” in 1902. Three years later, it had “125 students from twenty different states” (Plymouth Tribune).

An article in the nearby Plymouth newspaper reported on the mustering-in of a battalion of “Indiana state sailors” in 1909. “A ship will be provided for them,” it said.

The naval instruction on Lake Maxinkuckee covers all the elementary work done by naval reserves and by the government naval training stations. In addition, the formation of this battalion entitles Indiana to receive from the navy department a vessel for more extended drills and work in navigation on the Great Lakes.

Illinois has recently received the gunboat Nashville for this purpose and by next summer these Hoosier middies will probably receive a similar vessel.

A writer for the Indianapolis Journal in 1902 told potential tourists that “Visitors to Maxinkuckee during these months [July and August] will find the lake with quite a nautical appearance, the only feature lacking being the smell of the salt sea air.”

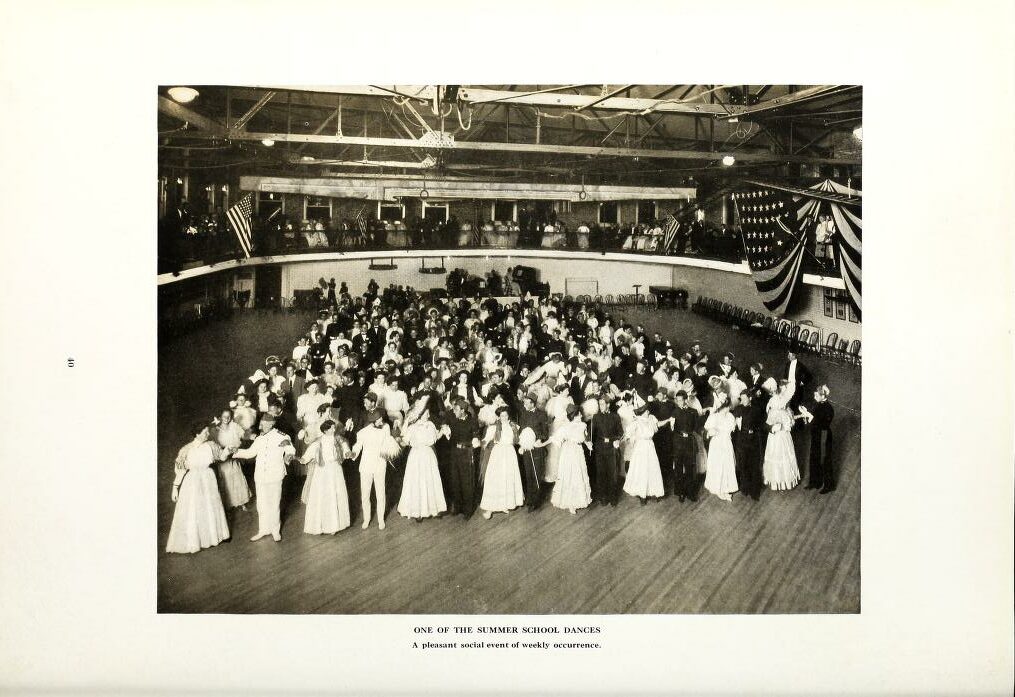

With the grounds illumined by Japanese lanterns, a ball was held at Culver that August. By 1910, a floating dance pavilion called “The White Swan“ enticed local dancers at the popular lake resort to come enjoy the summer nights along Aubeenaubee Bay. Guests sometimes arrived on the steamers that once plied Lake Maxinkuckee. In 1903, Civil War naval veteran (and native Hoosier) Admiral George Brown came to visit the Culver cadets.

(Naval students at a dance. This photo is from the institute’s 1912 catalog.)

(“Marlinspike Seamanship,” as taught in the northern Indiana flatlands. Students “will all be taught ship nomenclature, and the general principles which govern the building of wooden and iron ships. They will be instructed in the use of the compass, and the lead-line and the log. In connection with their work in seamanship, they will also be instructed in the courtesies and customs of the United States Naval Service. . . Cadets in the upper class will be taught the laws of gyratory storms. . . and will be required to learn thoroughly the ‘Rules of the Road’ for avoiding collisions at sea.”)

(In May 1907, Henri Marion was mentioned in this ad from Country Life in America. “Expert tutoring is given in any study; also a special course in modern languages, with the phonograph, under Professor Henri Marion, of the United States Naval Academy, and laboratory and other interesting special courses.”)

Possibly dealing with the effects of typhoid fever he contracted in Maryland in 1910, Henri Marion died in the hospital at Culver, Indiana, in August 1913 “after a general decline” — and not long after a fierce windstorm cut through the school and did huge damage.

The French instructor, interpreter, and pigeon-pioneer was buried at the Naval Academy’s cemetery in Annapolis. The Culver Military Academy continues its summer naval school to this day.

Do you have a photo of Professor Marion? I’m at staylor336 [at] gmail.com. And take your own dive into history at Hoosier State Chronicles.