Summer heat wave? One-hundred and one years ago in the Windy City, women would have had to tough it out, wind or no wind, due to living in “the most censored city in the United States.”

Actually, while Chicago, Illinois, pioneered many forms of public censorship — legislators there passed the first movie censorship law in America in 1907 — the swimsuit civil war was a widespread American phenomenon. Yet even as newspapers like the Chicago Daily Tribune protested wartime censorship in Paris — only French over the phone, s’il vous plait! (the paper called this “a form of censorship that was hard on Americans”) — as well as government ownership of telegraph wires in the United States, police officers on Chicago’s Lake Michigan beaches were on the prowl.

The above newspaper clip appeared on June 15, 1914, in the South Bend News-Times in South Bend, Indiana. It referred to a new “Paris bathing suit” that had been called immodest over in Chicago. Police officers were enforcing strict codes on the length of skirts allowed on Chicago public beaches. These fashions are hardly considered risqué today. It also seems like the Hoosier paper, by boldly publishing an image of the offending bathing suit on page 2, had different views altogether about ladies’ swimwear from the folks in charge over in the big city.

As Ragtime fashion took hold, America’s testy swimwear situation continued well into the 1920s. Yet it’s an interesting fact that many officers who served in urban swimwear patrols were women. This fabulous photo, taken on a Chicago beach in April 1922, speaks volumes about the complex fashion dilemmas that have always caused an uproar in America. The figure in the straw hat, wearing pants and a jacket and hauling off two offending bathers, is a woman. A generation earlier, in such an outfit, she herself might have been hauled off as a public offender and a threat to decency:

The South Bend News-Times was a fairly modern paper. Its editors had a sense of humor, and as they followed the fashion trends of the World War I era into the Jazz Age, they often took the side of the “modern girl.” Though the late Victorian Age — and what Mark Twain satirized as the Gilded Age, a time period he thought incredibly corrupt — could be far racier than it usually gets credit for, the News-Times offers some pretty good documentation of American public opinion as social mores began to change faster than ever.

The News-Times stands out for one other reason: it had a regular women’s page and was one of the first Hoosier newspapers to publish an abundance of photographs, a tactic largely intended to drive up sales. (The News-Times often struggled to stay in business and folded for good in 1938.)

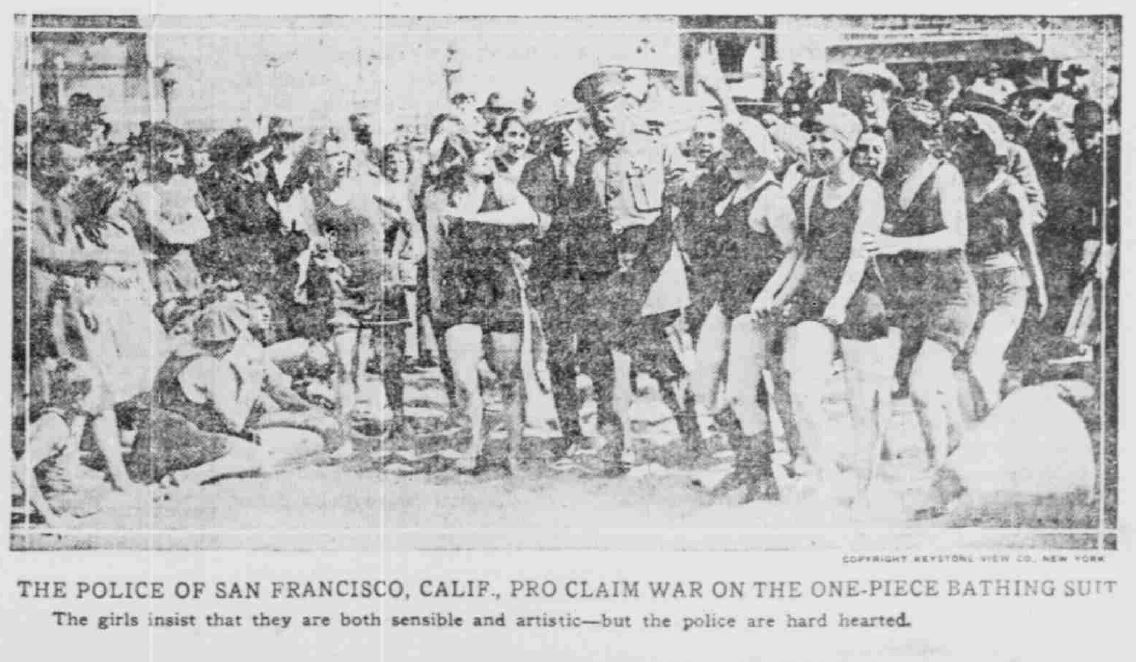

On August 15, 1920, in the section “Camera News,” the editors printed this photo of San Francisco police “claiming war” on the one-piece bathing suit out West. “The girls insist that they are both sensible and artistic,” the caption read, “but the police are hard-hearted.” It’s hard not to believe the editors in South Bend sided with the bathers.

Back in 1913, the News-Times published a photo of Mrs. Charles Lanning of Burlington, New Jersey. This case was more sobering.

In September 1913, Lanning was beaten by a mob on the Jersey Shore for wearing a “short vivid purple affair.” The caption reads: “An extreme slit on one side of the skirt is what started the trouble.” The New York Times carried the further information that Mrs. Lanning, who was married to a hotel proprietor, “was beset by 200 men at Atlantic City.” Lifeguards managed to break through the crowd and get her away from the “rowdies” who had apparently pelted her unconscious with sand and their fists. The crowd then followed her to the hospital “to get another glimpse at the suit.” When she got out of the hospital, some of her assailants were still standing there and Mrs. Lanning fainted.

American bathing suit ordinances, of course, met plenty of resistance. In March 1922, Norma Mayo, a 17-year-old girl living on Long Island, was already getting ready to commit civil disobedience the next summer against a New York judge, who had barely let her off the hook the previous summer for wearing an illegal swimsuit on the beach. Fittingly, the Norma Mayo clip appeared right next to an article about Mohandas Gandhi, “chief leader of the Indian non-conformists” against British control of his country.

Here’s a few more colorful stories from the annals of Hoosier State Chronicles about the Battle of the Beaches. Enjoy. And remember, suits may be getting smaller, but we’re a-growin’.

“Woman’s Sports Change Fashion” (December 4, 1921)

“Statuesque Dancer Won Health By Dancing in Bathing Suit on Shore” (November 27, 1921)

“Hawaiian Solons Debate Bathing Suit Legislation” (May 1, 1921)

“With Hands and Feet Bound She Swam 600 Yards Across a River” (August 11, 1913)

“Whether There Shall Be A Double Standard of Bathing Suits. . .” I’ll (July 29, 1913)

(South Bend News-Times, September 7, 1921)

(South Bend News-Times, September 7, 1921)

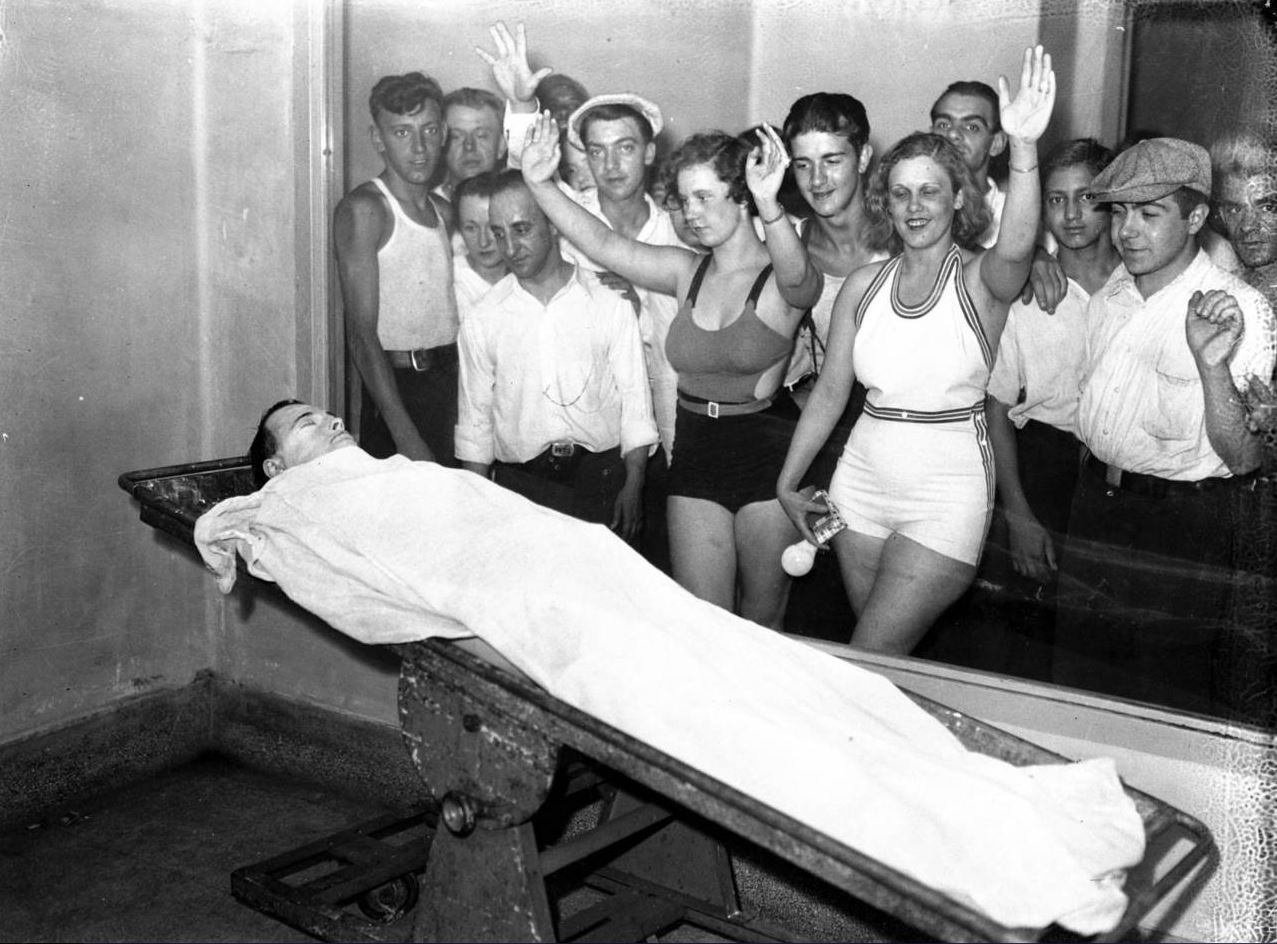

Betty Nelson and Rosella Nelson, dressed in bathing suits, view the body of Indianapolis gangster John Dillinger, aged 32, at the Cook County Morgue, Chicago, Illinois. Dillinger was killed outside the Biograph Theater in Chicago, July 22, 1934 — the height of the summer bathing season. (Chicago Tribune historical photo.)

OK, now TAKE TWO:

(Chicago Tribune historical photo.)

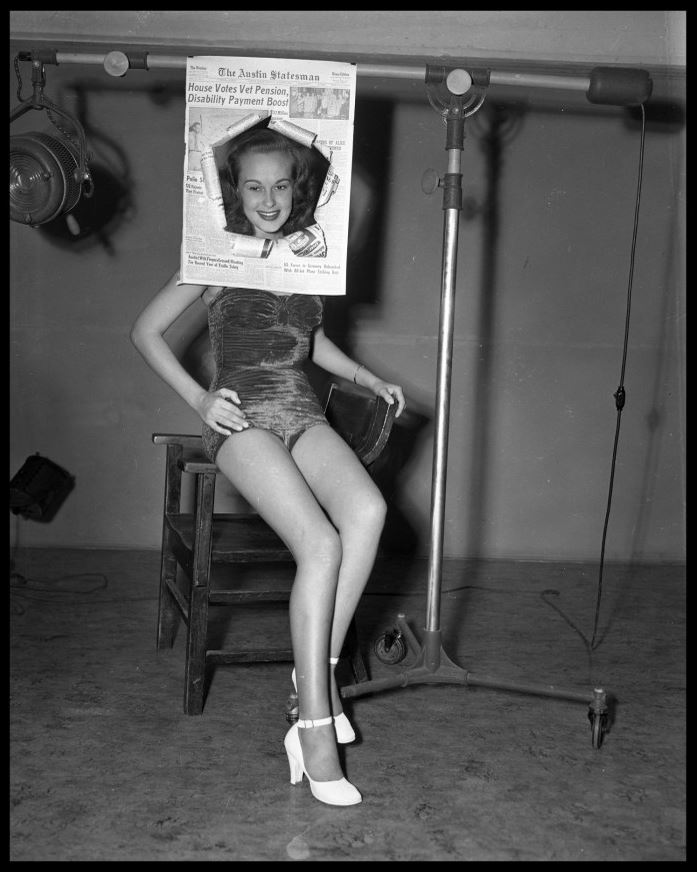

(She likes newspapers! University of North Texas Libraries/Austin Public Library.)