The best-known maritime disaster of 1912 was obviously the loss of the Titanic. Yet that winter had been fierce in the Midwest. From January to March, ice floes and so-called “icebergs” on Lake Michigan caused more than the usual disruption to shipping, and large parts of the lake froze over.

On March 11, with the great passenger liner’s doom still a month out, Chicagoans got something of a comic omen of that disaster. Afterwards, in late April, fishermen on the lakeshore near Gary, Indiana, made a surprise discovery — a find both morbid and funny.

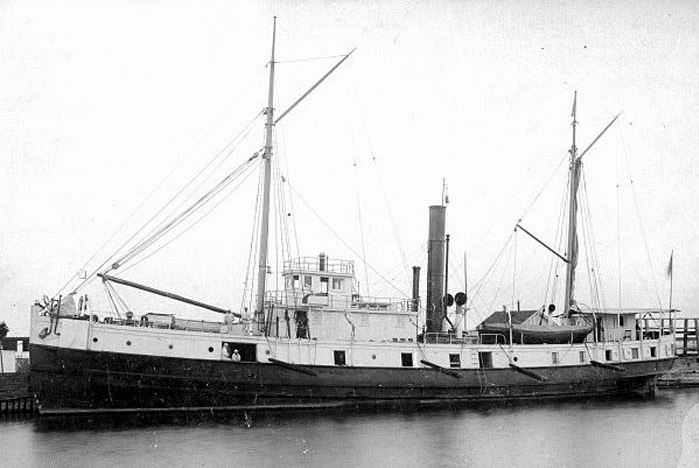

The short-lived cargo freighter Flora M. Hill had been outfitted in 1910 at Kenosha, Wisconsin, just north of Chicago. Until its demise in March 1912, the ship hauled goods and passengers between Milwaukee, Green Bay and the Windy City. A steel steamer weighing over four-hundred tons, the vessel belonged to the Hill Steamboat Line of Kenosha and was captained by Wallace W. Hill, son of Ludlow Hill, a commercial fisherman who worked out of Drummond Island, Michigan.

This vessel hadn’t always been a freighter, though. Originally, the Flora M. Hill was a U.S. government-owned lighthouse tender named the Dahlia. Built in 1874 by the firm of Neafie & Levy in the Philadelphia shipyards, then put into commission at Detroit, during the 1880s and ’90s the Dahlia was used by the U.S. Lifesaving Service to carry out annual lighthouse inspections up and down Lake Michigan and Lake Superior. The crew set out iron buoys near the treacherous shoals around the Straits of Mackinac and the rocky reefs off the northern U.P. They also submitted ice reports.

(The lighthouse tender Dahlia, later re-outfitted as the Flora M. Hill, in Chicago harbor, during the winter of 1891.)

The “ancient” Dahlia wasn’t considered a reliable vessel, though. Mariners even complained that she had “to run for shelter every time a slight breeze springs up, and is totally unfitted for service in early spring or late in the fall.” In summer 1903, the Lifesaving Service replaced her with then newer Sumac. Then in 1909, the Hill Steamboat Company of Kenosha purchased her outright from the government, turned her into a cargo vessel, and gave her a new name.

Almost as soon as she went back into service, as a ferry between Chicago and points north, the Flora M. Hill figured into an unexplained “wireless hoax.”

In August 1910, Chicagoans were thrown into panic by the report of a passenger ship on fire several miles out. The wireless operator aboard the Christopher Columbus picked up a distress signal sent in Morse Code. With summer vacationers traveling over the lake to Saugatuck, Michigan, and Indiana Dunes, folks ashore feared a passenger liner was going down. Reports then came in that the former lighthouse ship, the Flora M. Hill, was the burning vessel. Fire tugs went out to find it. As the Flora M. Hill cruised into Chicago, however, she reported no mishaps. The hoax was blamed on a radio prankster in the city.

(The Inter Ocean, Chicago, August 12, 1910.)

In January 1912, the freighter had a early foretaste of its icy fate. She left Waukegan on January 13, then went missing. Volunteer search crews lined the lakeshore from Grant Park to Evanston to watch out for them, as well as to keep an eye on the tugs Indiana, Alabama, Iowa, Georgia, and Kansas, all of them stranded in the thick ice but within view. Yet the twenty-five crew members from Kenosha, feared lost, soon showed up at Chicago harbor.

Two months later, however, the Flora M. Hill came to its end. Sailing from Kenosha with a load of brass bedsteads, automotive supplies, leather goods, and a bunch of ladies’ silk underwear — all produced at Wisconsin factories — the ship got stranded in heavy ice floes just two miles from the Carter H. Harrison crib in Chicago.

Captain Wallace Hill hadn’t judged the floe dangerous. Yet when jammed a hole through the iron, and with his propeller jammed, he had to send out distress signals. By noon on March 11, the captain and crew of thirty-one, including a 72-year-old pilot and a female cook, had to abandon ship.

Fortunately, unlike the crew and passengers of the H.M.S. Titanic, they managed to get to safety — by walking, crawling, and jumping over “ice islands.”

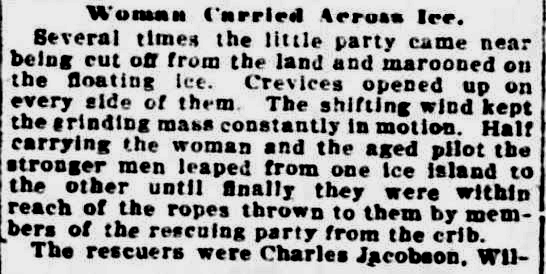

(The Inter Ocean, March 12, 1912.)

(The Inter Ocean, March 12, 1912.)

Like Ernest Shackleton’s crew after The Endurance was crushed in Antarctic pack ice, the crew of the Flora M. Hill struck out for terra firma. The water underneath them, in fact, was just thirty-seven feet deep. The cook, Mrs. Sanville, hadn’t even wanted to leave the ship behind — she loved her stove — and she as the men manned the pumps, she continued cooking food and brewing fresh coffee for them. Yet as the group headed for shore, they helped protect Sanville and the elderly pilot, Theodore Thompson, from exposure to the wind. They had been caught in a blinding snowstorm.

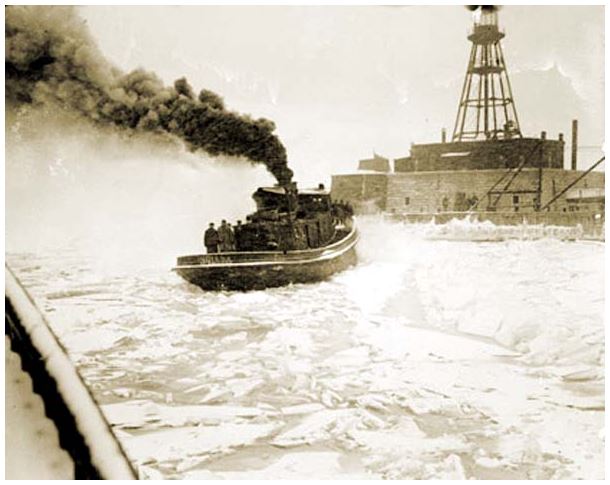

Not far out, the crew were met by the tug Indiana, which had sped out as fast as possible to their rescue after getting the distress call.

(The tugboat Indiana carried the crew to Chicago’s Dearborn Street landing.)

(The Inter Ocean, March 12, 1912.)

What was left of the vessel, sunk in shallow water, was dynamited by the Army Corps of Engineers in 1913 as a navigational hazard. In 1976, a diver rediscovered the wreck’s remains, still used as a “beginner’s dive site” for recreational underwater explorers. Some divers have even brought up automobile headlamps, vestiges of the early days of Wisconsin’s long-disappeared auto industry.

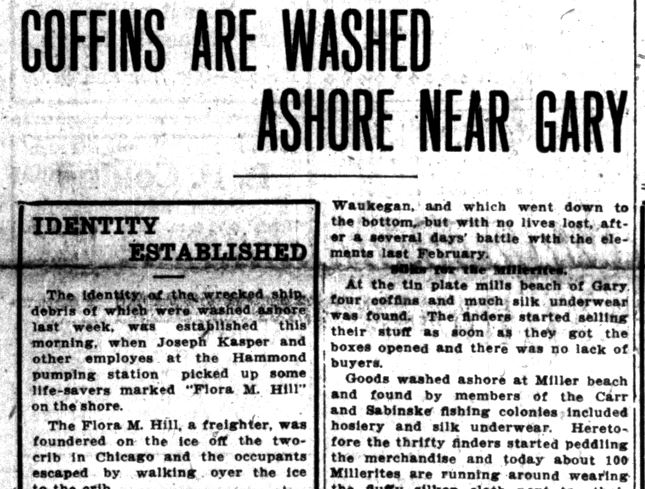

Not all the wreckage of the Flora M. Hill, however, went to the bottom of Lake Michigan.

On April 21, 1912, a week after the Titanic sank in the North Atlantic, fishermen at Miller Beach, Indiana — now part of Gary — reported some unusual finds there. Investigators confirmed the identity of this cargo when a couple of life jackets bearing the name Flora M. Hill turned up amid the wreckage. This story came out in Hammond’s Lake County Times on April 22 — directly beneath a report on the recovery of Titanic victims.

Comically, the morbid coffins — probably empty ones in transport — weren’t the only objects found to have washed up on the Indiana shore.