With the 2016 presidential primaries upon us, there’s more buzz than usual this year about a word with deep roots in Hoosier history — socialism. And, as always, religion remains a factor at the polling booths. This is also the first time in about a century that a major presidential candidate has openly disavowed “organized” religion. The last candidate to do so was Eugene V. Debs, a Socialist, skeptic, and native Hoosier who ran for president five times just before and after World War I. (Debs ran his last campaign from a federal prison in Atlanta in 1920, where he’d been sent for opposing the military draft.)

The topics of socialism and religion were hot as ever back in Debs’ day. In some ways, that debate looks eerily familiar, with skeptics accusing churches of abetting social inequality, and believers often firing back with equally broad strokes about the dangers of revolution. While plenty of American labor activists were religious — including major voices like Mother Jones and Terence Powderly — Debs and many more were agnostic. Indiana Socialist, the newspaper of the Marion County Socialist Party in Indianapolis, tended toward religious skepticism, often printing ads for books that questioned Christian beliefs and especially church authorities. Since most American workers were Christian, however, Socialist leaders were wary of alienating them, and Debs found much in the ethics of the New Testament to applaud.

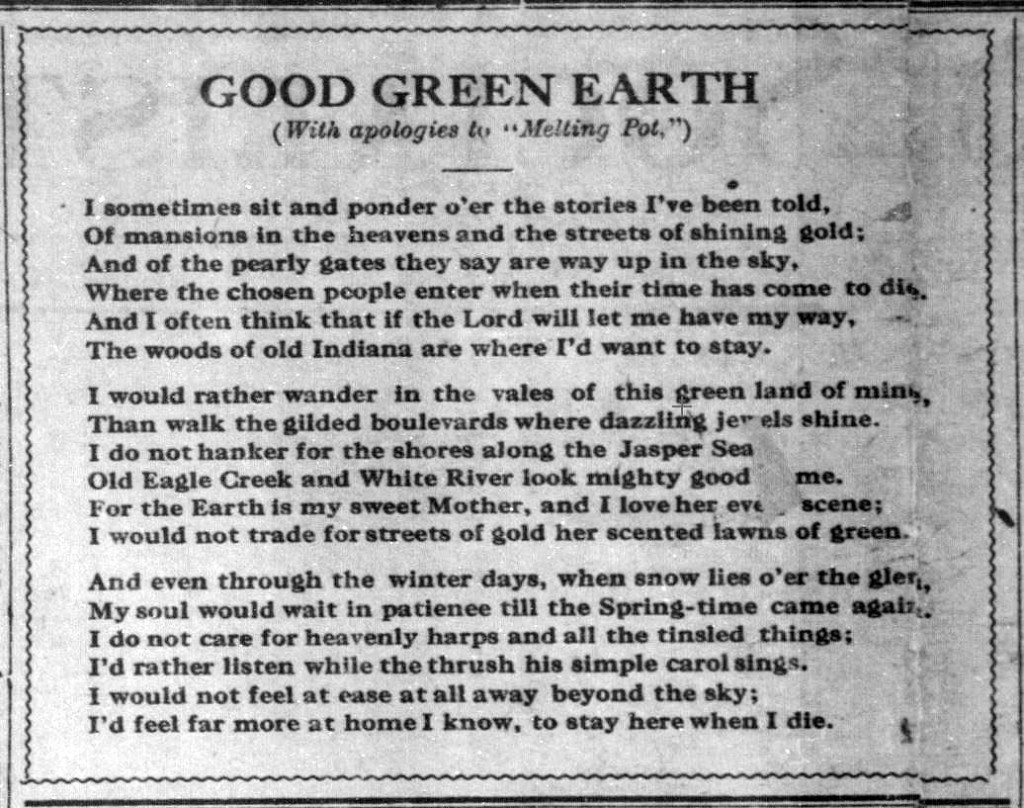

Some of the barbs thrown at religion are about as nuanced as the ravings of any old street preacher. But some it even believers might find stirring. In July 1913, on the heels of a Fourth of July visit by Mother Jones to Irvington on Indianapolis’ East Side, Indiana Socialist published just such a poem.

(The “Socialist literature wagon” once sat at the corner of Market and Pennsylvania streets in downtown Indianapolis. Indiana Socialist, April 26, 1913. The Socialist Party of Indianapolis’s 1913 campaign platform called for such things as public playgrounds, urban beautification, and equal pay for equal work. The newspaper estimated that Marion County, Indiana, alone had about 8,000 Socialist voters in 1913, plus others whom it alleged were kept from voting by their employers.)

The poem’s author was Henry M. Tichenor (1858-1924). Along with fellow Midwesterners Clarence Darrow and Robert Ingersoll, Tichenor was one of the most outspoken American freethinkers of his time. An influential Socialist writer and editor in Missouri, Tichenor loathed organized Christianity. Contrary to popular belief, many Americans were disgruntled with churches a century ago, and Tichenor’s popular, down-to-earth style made him popular even in the Midwest, whose radical history runs almost as deep as its reputation for staunch conservatism.

(Harry M. Tichenor in 1914.)

Unlike the Marxist intellectuals who twisted Socialism to serve the greed of dictators and party elites, Tichenor was no high-falutin’ “comrade” inventing totalitarian “Newspeak” — the language of George Orwell’s memorable dystopian lampoon, 1984. Yet his long, comic tirades against “holy humbug” (books with titles like The Life and Exploits of Jehovah) are basically the scribblings of a humorist, not a serious historian. They probably never bothered anyone except fundamentalists who insisted on a literal reading of every story in the Bible.

In 1913, Tichenor was a regular poetry contributor to the St. Louis-based National Rip-Saw, “America’s Greatest Socialist Monthly.” He was also cranking out fiery anti-capitalist pamphlets with titles like “The Rip-Saw Mother Goose,” “Rip-Saw Socialism Songs,” and “Woman Under Capitalism.” That year he started printing a socialist journal of his own, The Melting Pot, a political and comic firecracker.

(The International Socialist Review, April 1913.)

sdfsf

(Rhymes of the Revolution, 1914. Courtesy Debs Collection, Indiana State University.)

sdfsdf

(