The “religion vs. science” debate has been a hot media sensation since 9/11. Syria’s refugee crisis is causing further argument over why some believers haven’t helped people obviously in need, though many have. But venomous debates over religion and refugees aren’t new to American history.

Black History Month reminds us that religious voices have played a profound role in American struggles for justice — with many of the most religious Americans being treated as criminals for their pains on behalf of others. Some historians have even remarked that the Civil Rights movement was “primarily a religious and spiritual movement.” The work of Martin Luther King, Jr., Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman, John Brown, William Wilberforce, David Livingstone, and many others drew powerfully on their interpretation of faith. In fact, you could even argue that the African and African American encounter with Christianity — and vice-versa — eventually unlocked religion for many Europeans and Americans who were only nominally Christian to begin with.

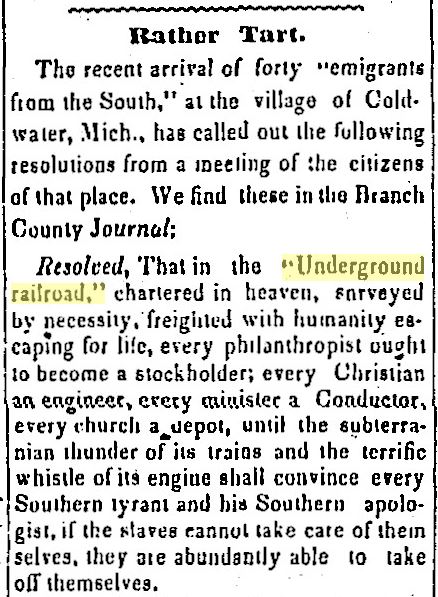

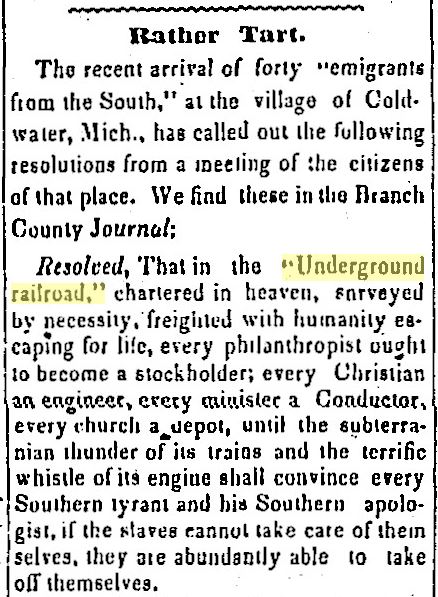

Whatever the truth there may be, radical Christianity rang out loud and clear during one of America’s (and Canada’s) first refugee crises — the exodus of fugitive slaves seeking asylum under “the North Star.” That exodus took thousands of refugees across the rural Midwest.

Abolitionist history is certainly full of iconic Christian imagery. When a slave from Virginia, Henry Brown, experienced a “heavenly vision” and decided to mail himself out of bondage in 1843, he had himself concealed inside a 3-foot by 2-foot dry goods box or “pine coffin.” Lined with wool and containing only a few biscuits and some water, the box and its occupant were carried north, delivered after a week on the road to the office of Passmore Williamson, a Quaker merchant active with the radical Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society. Like a well-known Byzantine icon of Jesus, “the Man of Sorrows” — which shows Jesus rising from the dead and an equally tiny box — Henry “Box” Brown climbed out in front of a group of Philadelphia abolitionists and asked “How do you do, gentlemen?” A fabulous engraving of the event was given the name “The Resurrection of Henry Box Brown.”

(Passmore Williamson, a Pennsylvania Quaker, at Moyamensing Prison in 1855, where he was jailed for helping Jane Johnson and her two sons escape from slavery. Williamson was also an early advocate of voting rights for women.)

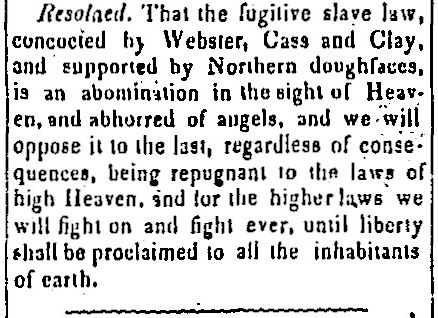

Several major “routes” of the Underground Railroad passed through Indiana, leading to farmhouses and barns in the Wabash Valley, the fields around Quaker-dominated Richmond and Fountain City, and the swamps and prairies north of Indianapolis. Yet Hoosiers — like other Americans — were deeply torn over whether to obey the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act, a controversial law that made it illegal for any citizen to assist a runaway slave and exacted harsh penalties for helping refugees. The federal law was absolutely designed to protect humans defined as “property” and even as “livestock.”

Many Christians, of course, were slaveholders themselves, though their views often depended on whether they lived in the North or South. Northern and Southern Baptists, for example, had sharp differences of opinion on slavery. Though Methodism’s founder John Wesley wrote against human bondage in 1778, Southern Methodists often owned slaves. Ministers who didn’t take their congregation’s — or government’s — line on slavery were sometimes kicked out of the pulpit or physically attacked. At least a dozen chapels built by anti-slavery Baptists and Methodists in Jamaica were burned down by white settlers.

The religious situation was never simple. The Jesuits, whose famous South American missions were admired by Enlightenment philosophers as an experiment in earthly utopia, had long owned slaves. Just two years before Pope Gregory XVI spoke out against the slave trade in 1839, Jesuit priests in Maryland were putting slaves to work on plantations to support Georgetown University, a Catholic school built by slave labor and where students brought their slaves to class. (In 1838, the Jesuits sold thirty of them to the ex-governor of Louisiana, whose son was a student of theirs.) One Maryland priest used the Bible to defend slave ownership. Yet the Jesuits were no more guilty than the religious freethinker Thomas Jefferson, who along with forty other signers of the Declaration of Independence, owned slaves while announcing “All men are created equal.” Jefferson used a blade to create a famous Bible of his own, cutting out the miracles and superstition to focus on Jesus’ ethics and morals. Jefferson, however, went to his grave a slave-owner, having thought about it for fifty years.

(The cutting-room floor of Jefferson’s Bible. Though he included Luke 12:48 — “To whomever much is given, of him much shall be required” — the master of Monticello must have been uncomfortable with the next passage, “I am come to cast fire on the earth, and how I wish it were already kindled! …Do you suppose that I am come to send peace on earth? Nay, but a sword.” Jefferson sliced it out. As the English critic of slavery, Dr. Samuel Johnson, put it, “How is it that we hear the loudest yelps for liberty among the drivers of negros?” Contemporary science was no help to Africans. Harvard biologist Louis Agassiz, the most famous American scientist of his time, commissioned the best-known daguerreotypes of African slaves to provide evidence for the old theory of “polygeny,” or “separate creation” of the human races. Originally a heretical religious theory, the scientific version was given credence by the atheists Voltaire and David Hume. Voltaire believed that whites and blacks were different species.)

Not all American Christians appreciated the politicizing of the pulpit. Under the pen name “Q.K. Philander Doesticks, P.B.,” humorist Mortimer Thomson satirized their reaction to “politico religious hash” — i.e., hyper-political sermons. “Doesticks,” who grew up in the Midwest, wrote for Horace Greeley’s anti-slavery New York Tribune and even did a famous undercover report on a huge slave sale in Savannah, Georgia, where he posed as a potential buyer to get the full scoop. Thomson received death threats for his exposé of slave auctioneering. As a satirist, he was much admired by Mark Twain.

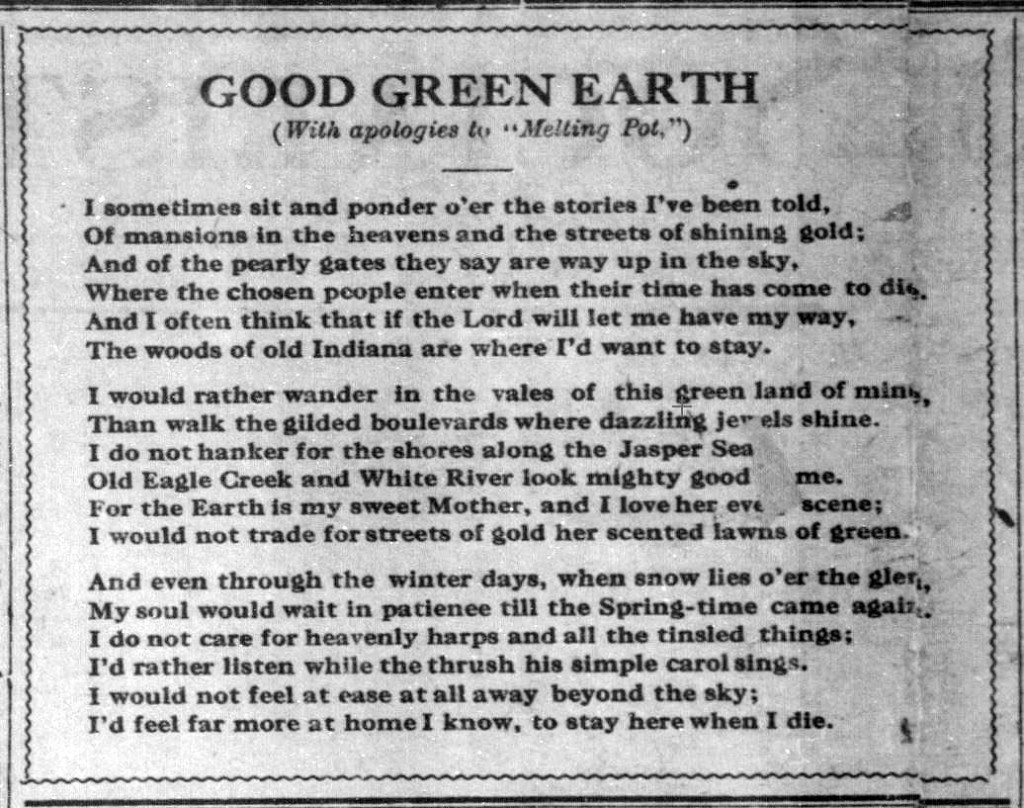

(Weekly Indiana State Sentinel, Indianapolis, October 2, 1856.)

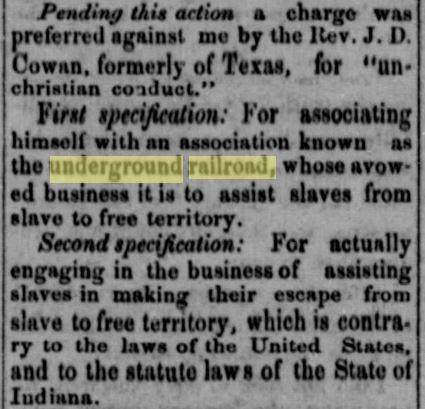

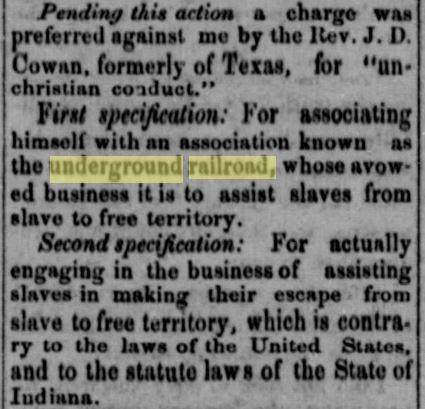

Indiana was no stranger to this religious battle. In 1855, the year Passmore Williamson went to prison in Pennsylvania, the Reverend Thomas B. McCormick got into hot water with congregations and the law in Princeton and Mechanicsville, Indiana, two small towns between Evansville and Vincennes. Gibson’s flock were Cumberland Presbyterians, a branch mostly centered in Kentucky and Tennessee.

Princeton lay on a main line of the Underground Railroad running up the Wabash Valley. Unlike most “agents” and “stationmasters” on the Railroad, Rev. McCormick made no secret of his hatred for the Fugitive Slave Act. He actively aided runaways from Kentucky and preached on the topic of slavery and its sinfulness. A native Kentuckian himself, McCormick had been a minister in southern Indiana for fourteen years when he ran afoul of the law.

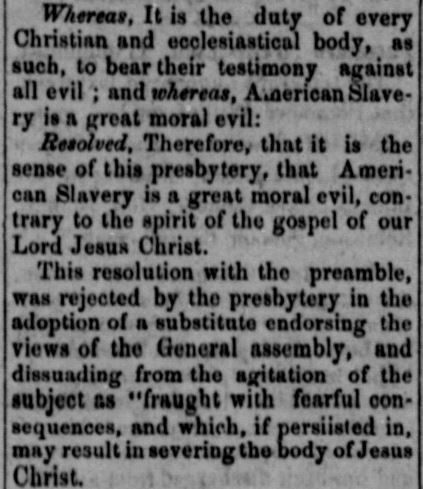

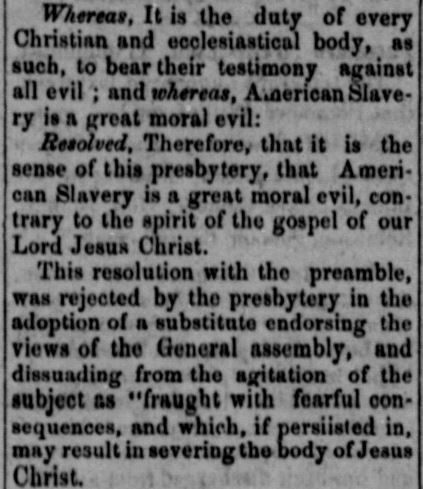

At a session of the Indiana Presbytery of the Cumberland Presbyterians, who met at Washington in Daviess County in 1855, church elders passed a resolution (17-3) stating “That it is not expedient to discuss the subject of American Slavery from the pulpit.” McCormick had just preached an anti-slavery sermon. He ignored the elders.

(Indiana American, Brookville, November 16, 1855.)

(Indiana American, Brookville, November 16, 1855.)

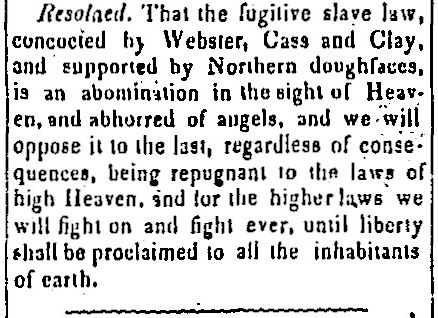

McCormick then put forward a resolution of his own, which was rejected by the presbyters:

(Indiana American, Brookville, November 16, 1855.)

When the Cumberland Presbyterians tried to silence Thomas McCormick from preaching, the reverend left and joined the Congregationalists — a denominational cousin of the Presbyterians but who were more united in their condemnation of slavery. McCormick’s activity piloting fugitives north toward Michigan and Canada, however, soon got him indicted by a Kentucky grand jury.

Under the 1850 federal law, Kentucky Governor Lazarus Powell was authorized to request the governor of neighboring Indiana — a technically “free” state, though many Hoosiers were pro-slavery — to extradite any Hoosier caught helping refugees evade slave catchers, who often traipsed onto Indiana soil. Governor Joseph Wright (namesake of Wright Quadrangle at Indiana University) complied with the noxious law. Like those he helped, Rev. McCormick himself had to flee to either Ohio or Canada, as “a large sum of money was offered for his body.” McCormick ran for the governorship of Ohio in 1857 on “the Abolition ticket” and wasn’t able to return to Indiana until 1862, when Governor Oliver P. Morton assured him he would be safe here. He died in Gibson County in 1892.

Calvin Fairbank, an abolitionist and Methodist minister who ferried slaves over the Ohio, was less fortunate than McCormick. For over a decade, Fairbank helped at least forty runaways slip into the interior of Indiana, many of them making it to the farm of Levi and Catherine Coffin in Fountain City, just north of Richmond. Coffin, a Quaker from North Carolina, was called the “President” of the Underground Railroad.

In 1851, with the complicity of Governor Wright and the Clark County sheriff in Jeffersonville, Fairbank was arrested on the way to church by Kentucky marshals, who extradited him across the river to Louisville. (Some versions say he was “kidnapped.”) Fairbank eventually spent thirteen years at the old Kentucky State Penitentiary in Frankfort, where guards mercilessly beat him and lashed him with whips, by some accounts a thousand times, by others 30,000 times. With his body broken, he moved to western New York, where he died in poverty in 1898, an almost forgotten hero of American freedom.

(Calvin Fairbank.)

The great abolitionist and former slave Frederick Douglass, who lashed out at American hypocrisy, once proclaimed: “Between the Christianity of this land and the Christianity of Christ, I recognize the widest possible difference.” The Anti-Slavery Bugle, a newspaper published in Lisbon, Ohio, quoted Douglass’ words on the fervently Baptist Newton Craig, cruel superintendent of the Kentucky State Penitentiary and Fairbank’s torturer.

According to an 1860 history of the prison, written by a friend of Captain Craig’s, the jailer’s ancestors had been imprisoned in colonial Virginia “for preaching the gospel” as dissenting Baptists, against the Anglican state church. In spite of his fervent religion, Craig, as abolitionists said, nevertheless had “the most inveterate hatred” toward “negro-stealers.” The jail-master earned a small fortune during his eleven years in charge, using convicts on nearby plantations, and is said to have “delivered long sermons to the inmates in his care.” According to a story mentioned by Frederick Douglass, he broke an expensive cane on Calvin Fairbank’s head:

(Frederick Douglass on Newton Craig. Anti-Slavery Bugle, Lisbon, Ohio, April 12, 1856.)

(Kentucky State Penitentiary. The note reads: “This is some Bird Cage. Looks like a church.” Frederick Douglass once wrote of America: “The church and the slave prison stand next to each other… [T]he church-going bell and the auctioneer’s bell chime in with each other; the pulpit and the auctioneer’s block stand in the same neighborhood.”)

Not long after Fairbank’s arrival behind bars, several other resisters joined him, including Delia Webster (a Vermont-born schoolteacher from Lexington and the only woman at the prison) and former slave Lewis Hayden. A lesser-known inmate was the Irish immigrant Thomas Brown, who with his wife Mary McClanahan Brown had posed as a traveling merchant and “notions pedlar” downstream from Evansville, Indiana. Operating on the Kentucky side of the river near Henderson, the Browns smuggled refugees under curtains in their wagon to the riverbank. Brown was arrested by marshals near the mouth of the Wabash and sentenced to a prison term in Frankfort, where he witnessed the murder of a free black man from Evansville by guards. Released in 1857, Brown wrote an exposé of the wardens, published in Indianapolis that year as Three Years in Kentucky Prisons.

By the end of the 1850s, anti-slavery voices had grown stronger than ever. The religious undertones were clear: from the fascinating dream-visions and out-of-body experiences of Harriet Tubman to the fiery Old Testament furor of John Brown. While the actions of Christians like prison warden Newton Craig and many more made Frederick Douglass’ suspicion of the churches a fair criticism, the “voice in the wilderness” was now crying strong.

(Weekly Reveille, Vevay, Indiana, August 18, 1853.)

Hoosier State Chronicles provides access to many other fascinating news clips about the Underground Railroad, all of them available for free on our search engine. Here’s a few of the best:

A reprint in the anti-Underground Railroad Daily State Sentinel (Indianapolis) about the impact of the refugee crisis on public opinion in Vermont, “A Change of Sentiment,” July 8, 1858.

An editorial from the Daily State Sentinel criticizing Indiana judges for protecting “the n—-r population,” October 12, 1857.

“Calvin Fairbank Dead,” Indianapolis News, October 14, 1898.

“A Kidnapper Caught,” [on Thomas Brown], Evansville Daily Journal, June 2, 1854.

“A Collision on the Underground Railroad,” Terre-Haute Journal, September 15, 1854.

An article against “The Abolition Editor of the [Indianapolis] Journal,” Daily State Sentinel, May 5, 1856.

An editorial against Illinois abolitionist Owen Lovejoy, brother of murdered abolitionist printer Elijah Lovejoy, Daily State Sentinel, August 9, 1856.

“Return Trips of the Underground Railroad,” about the miserable conditions refugees that found in Ontario, Daily State Sentinel, October 24, 1857.

A reprint from the Detroit Advertiser equating the Underground Railroad with theft, “Arrival of Twenty-Six Fugitive Slaves at Detroit,” Daily State Sentinel, November 8, 1859.

A statement from a Senate report arguing that the Underground Railroad would be cause for war with a foreign nation, Evansville Daily Journal, January 23, 1861.

A reprint from the New York Express, written during the Civil War, mocking abolitionists as part of a procession leading the American people toward “the Limbo of Vanity and the Paradise of Fools,” Daily State Sentinel, October 17, 1862.

Contact: staylor336 [AT] gmail.com

Like this:

Like Loading...

(Lake County Times, June 22, 1913. Hoosier State Chronicles recently portrayed Muncie’s

(Lake County Times, June 22, 1913. Hoosier State Chronicles recently portrayed Muncie’s