Did you know that environmental laws, labor and women once clashed, causing feathers to fly? One little known battle from the days of the “plume boom” took place in 1913. The setting? The Indiana State House.

Nineteen-thirteen happened to be the same year that W.T. Hornaday, one of America’s foremost wildlife biologists and conservationists, published a book called Our Vanishing Wildlife. Born on a farm near Plainfield west of Indianapolis but raised in Iowa, Hornaday had traveled around South Asia, served as Chief Taxidermist at the Smithsonian, then became the first director of the New York Zoological Society, later renamed the Bronx Zoo. In 1889, the former Hoosier published the first great book on the near-total destruction of the American bison — the species seen bounding across Indiana’s state seal but which was wiped out here long ago by the pioneers.

Already an expert on the buffalo’s demise, by 1913 Hornaday had begun lashing out at the wholesale slaughter of birds:

From the trackless jungles of New Guinea, round the world both ways to the snow-capped peaks of the Andes, no unprotected bird is safe. The humming-birds of Brazil, the egrets of the world at large, the rare birds of paradise, the toucan, the eagle, the condor and the emu, all are being exterminated to swell the annual profits of the millinery [hat-making] trade. The case is far more serious than the world at large knows, or even suspects. But for the profits, the birds would be safe; and no unprotected wild species can long escape the hounds of Commerce.

Feathers have been part of human attire for millennia. But by the early 1900s, massive depredations by European and American hunters around the globe had wreaked havoc on avian populations. Bird hunters were now the arm of industrial capitalism, with the harvesting of birds for ladies’ hats belonging in the same category with other natural resources like coal, diamonds and oil.

Although the center of the global feather trade in 1913 was London — where feather merchants examined skins and quills in enormous sales rooms, then bid on them like other commodities — New York and Paris were involved a big part of the trade. All three cities had become epicenters of women’s fashion. And women weren’t only the consumers of feathers: of the roughly 80,000 people employed in the millinery business in New York City in 1900, the majority were women.

In 1892, Punch, the British satirical magazine, took a jab at women, who it considered the driving force behind the decimation of wild bird species and their consumption in the West. It failed to point out, of course, that the hunters themselves — the ones who did the slaughtering — were men.

In the U.S. and Europe, bird-lovers created several societies to stem the global slaughter, with scientists helping to provide the grisly details that would provoke moral outrage. Women made up most of the membership in these societies, including the new Audubon Society — named for John James Audubon, the French-American naturalist who lived for years along the Ohio River across from Evansville, Indiana. An especially well-known voice was the great ornithologist and writer William Henry Hudson, born to American parents in Argentina, where he spent his childhood bird-watching in the South American grasslands. Yet in the days before zoom lenses and advanced photography came along, even respected field naturalists like Audubon and Hudson had relied on guns to “collect” species and study them.

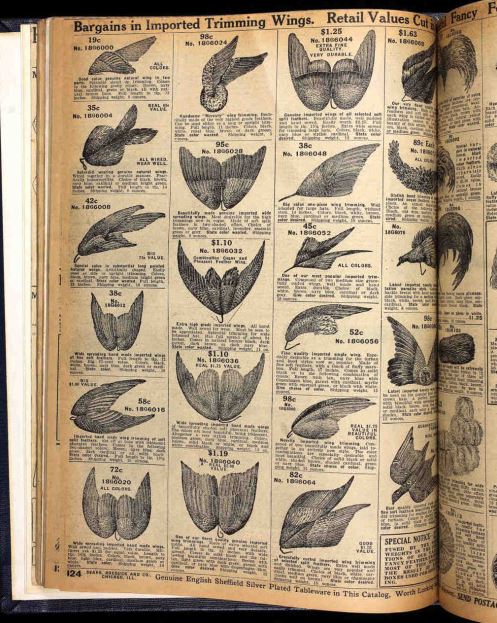

In 1913, W.T. Hornaday gave specifics on the “plume boom.” At one London feather sale two years earlier, ten-thousand hummingbird skins were “on offer.” About 192,000 herons had been killed to provide the packages of heron feathers sold at a single London auction in 1902. Other popular feathers came from birds like the egret, eagle, condor, bustard, falcon, parrot, and bird of paradise. When exotic bird feathers weren’t available or affordable, millinery shops used the feathers of common barnyard fowl.

While the Florida Everglades were a popular hunting ground, the “Everglades of the North” — Indiana’s Kankakee Swamp, now mostly vanished — was another commercial source for feathers, mammal pelts, and another item that’s out of fashion today: frog legs. Yet the worst of the commercial hunting was in Florida, where ornithologists wrote of how hunters shot mother birds, especially herons and egrets, and left nestlings to starve, endangering the entire population for quick profit, as the mother’s plumage was at its most spectacular during nursing. Conservationist T. Gilbert Pearson described finding “heaps of dead Herons festering in the sun, with the back of each bird raw and bleeding” where the feathers had been torn off. “Young herons had been left by scores in the nests to perish by exposure and starvation.” The much-publicized murder of a young Florida game warden, Guy Bradley, in 1905 helped galvanize the anti-plumage campaign and spurred the creation of Everglades National Park.

Since bird feathers and skins were often valued at twice their weight in gold and were readily available to ordinary Americans and Europeans even in urban areas, women and children found a decent supplemental income in stoning birds to death or killing them with pea-shooters, stringing them up, and selling them to hat-makers. Children also robbed eggs for collections. Farmers frequently shot or trapped even great birds like the eagle when they preyed on chickens, with one scowling, utilitarian farmer in New Hampshire blasting “sentimentalists” who thought the eagle had “any utility” at all.

By 1913, legislators in the U.S. and Britain had been urged to consider “anti-plumage” bills. Yet the profits involved in millinery — and the ability of consumers to buy hats in markets not covered by the laws — were big hurdles. As early as 1908, anti-plumage bills were being debated in the British Parliament, but they took years to pass. (Britain’s passed in 1921.) States like New York and New Jersey were considering a ban on the trade in wild bird feathers around the same time. New York’s went into effect in July 1911, but not without concern for its effects on feather workers, some of whom argued that they had no other way of supporting themselves.

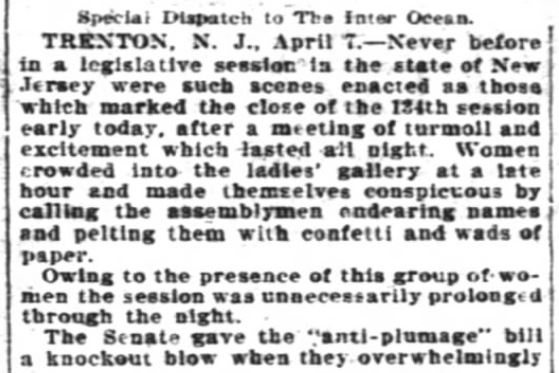

The debate in New Jersey took a more comic turn. If this news account can be trusted, women came to the Senate in Trenton and pelted legislators with paper balls.

One crusader for wild birds was the former mayor of Crawfordsville, Indiana, Samuel Edgar Voris. In 1913, he joined the likes of the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds and the Audubon Society by taking the battle to the Indiana Legislature. For a few weeks early that year, Hoosier politicians and journalists debated what became known as the “Voris Bird Bill.”

It was a strange fact that Voris authored the bill, since back in 1897 he’d been called “one of the crack shots of the United States,” often competing in shooting tournaments around the country. Voris was born in Dayton, Ohio, in 1854. His father may have been the Jerry or Jeremiah Voris who ran a meat market in downtown Terre Haute. (According to one ad, that Jerry sold elk meat next door to the offices of the Daily Wabash Express, ran a grape farm, and might be identical with one of Crawfordsville’s first undertakers. He also might have known something about preserving the bodies of birds — or at least had an interest in birds. In 1870, the Terre Haute butcher offered one “fine healthy screech owl” to State Geologist John Collett to be put on display at the State Board of Agriculture.)

Samuel E. Voris was out West in 1876, the year the Sioux wiped out Custer and the 7th Cavalry at the Little Bighorn. The 21-year-old Voris must have seen the slaughter of American bison up close as he traveled in an overland wagon train to the Black Hills of South Dakota. His 1920 obituary in the Crawfordsville Daily Journal mentions that Voris’ wagon team was attacked by Indians on the way out. Yet the future Crawfordsville mayor “had the honor of being in the wigwam of Spotted Tail, one of the big chiefs of a noted tribe of Indians at that time.”

Voris returned to the Midwest, settling in Crawfordsville, where he was a member of General Lew Wallace‘s “noted rifle team,” a group of crack recreational sharpshooters. (The Hoosier soldier, ambassador and author of Ben-Hur was also an avid hunter and fisherman, often visiting the Kankakee Swamp.) Voris’ obituary noted that the mayor “was a man of peaceful disposition in spite of his love for firearms.” He knew about animals: his investments in livestock and insurance made him one of the richest men in Crawfordsville. He also served as postmaster and was involved in civic-minded masonic organizations, including the Tribe of Ben-Hur, Knights of Pythias and Knights Templar. General Wallace, former U.S. Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, probably had something to do with the fact that in 1898, Voris was granted an audience with the Turkish Sultan while traveling in the Middle East. Voris apparently loved camels, too: in 1914, he fell off one in Crawfordsville when the camel got spooked by an automobile. The man landed on his head and suffered a scalp wound.

In 1911 and again in 1913, Montgomery County elected their former mayor to the Indiana House. Representative Samuel E. Voris was the author of at least two bills in 1913 concerning the treatment of animals. (Another bill, written by a different representative, proposed “a fine of $500 for anyone who willfully poisons [domestic] animals.”)

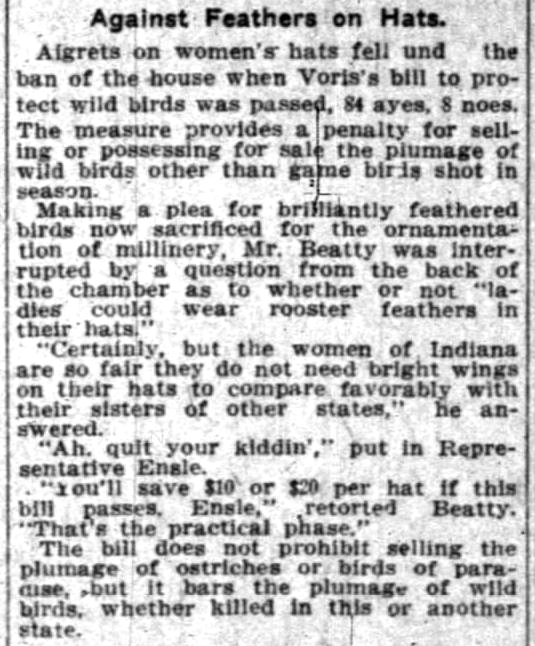

The “Voris bird bill” won strong support from conservation and animals rights groups in the Hoosier State, but sparked a bit of humor on the floor of the House of Representatives.

The “Voris bird bill” passed the Indiana House, but objections arose in the Senate, with a Senator Clarke arguing that it would harm Indiana milliners while not prohibiting the sale of hats made outside the state from being sold here. Another senator objected on the grounds that national legislation was needed to make it truly effective — even though that was slow in coming. The bird bill was killed in February.

Yet while some women opposed it, one correspondent for the Indianapolis Star came out in defense of the anti-plumage campaign.

Marie Chomel, who wrote under the pen name Betty Blythe, had a weekly column in the Indianapolis Star for years. (She came from a newspaper family. Her father Alexandre Chomel, son of a nobleman exiled by the French Revolution, had been the first editor of the Indiana Catholic & Record.) As a reporter for the Star, Betty Blythe became the first woman ever to lap the Indianapolis Motor Speedway in a race car, riding shotgun with Wild Bob Burman “at a terrific speed” on a day when two drivers were killed there. It happened in August 1909.

Chomel frequently wrote about fashion, but thought that exotic plumage was inhumane and had to go. She published her views on the bird bill in the Star on February 13, 1913.

Chomel agreed with Voris’ motives. Yet like English novelist Virginia Woolf, who criticized a sexist statement from British radical journalist H.W. Massingham that pinned the blame for bird deaths squarely on irresponsible women, the Indianapolis Star didn’t let men off the hook, either.

Though wildlife protection laws and groups like the Audubon Society helped make the case for saving birds, two other events were even more influential in ending the feather trade.

Oddly, the outbreak of World War I saved millions of birds. Disruptions to international shipping and wartime scarcity made the flamboyant fashions of the Edwardian period look extravagant and even unpatriotic. Tragically, as women went into the workplace and needed more utilitarian clothing, “murderous millinery” gave way to murderous warfare, fueled by the same forces of imperialism and greed that had killed untold creatures of the sky.

Even more effective, fashion changes and class antagonism caused upper-class women to adopt new apparel like the “slouch” and “cloche” hats and new hairstyles like the bob. As hair was being cut back, elaborate feather ornaments made little sense. In the U.S. and the UK, where upper-class and upper-middle-class women made up most of the membership in groups like the Audubon Society, female conservationists sometimes targeted women of other classes for sporting feathers. Slowly, they instigated change.

Fortunately, most fashion enthusiasts would probably agree that the cloche hats of the 1920s, which drove hunters and feather merchants out of business, are more natural and beautiful than the most literally “natural” hats of a decade or two before.

Contact: staylor336 [AT] gmail.com