Yesterday’s post sent a few heads rolling, but we can’t get enough this October. Here’s a follow-up from medical science.

Contrary to popular belief, Washington Irving didn’t invent the tale of Ichabod Crane and the Headless Horseman from scratch. Said to have been a Hessian mercenary decapitated by a cannonball during the American Revolution, the dark rider was left to roam the Catskill Mountains near a Dutch settlement in New York called Sleepy Hollow.

Written while Irving was living in Europe, the story actually drew on German and Irish folklore, where similar specters haunt the realm of the living. There’s also a long list of early Christian saints (known as cephalophores) who according to hagiographic legends, picked up their own heads after execution and walked away — or at least uttered an important message before going silent at last. Saint Gemolo, who probably came from Germany or Scandinavia, was even said to have grabbed his head in his hands and ridden away on horseback.

Germans told of Der Kopfloser Reiter, a shadow figure that rides out of the forest, hunts down malefactors, warns the living, and — like his cousin the Irish banshee — announces the approach of death. Irish folklore includes reports of the dulachán or dullahan, a specter that also rides a dark horse, but he comes with some frightening accouterments: a whip made from a human spinal cord, a funereal bone cart. . . Like the screaming banshee, the apparition of a dullahan portends encroaching death. And like Washington Irving’s horrid creature, the dullahan carries its own severed head, believed to look like moldy cheese. Don’t look at the specter to find out: he’ll throw blood in your face.

With the mass emigration of Irish peasants overseas, especially after the brutal Famine of the 1840s, these stories got carried to the U.S. Some were twisted into hyper-literary forms. But apparently the actual banshees didn’t care for transatlantic sea voyages and stayed home in their native terrain. Headless horsemen, though, weren’t totally fictional.

In 1870, doctors in England offered a rational explanation for what were actually real sightings of decapitated equestrians. These sightings, of course, occurred in war zones.

Readers of the Terre Haute Weekly Gazette encountered the following clip from The Lancet, a famous London medical journal. Founded in 1828, just nine years after Irving’s Sleepy Hollow came out, The Lancet was the brainchild of Thomas Wakley, a crusader against “incompetence, privilege, and nepotism” in British society — and flogging. The doctor was also a radical Member of Parliament. Wakley’s sons edited The Lancet until 1909.

The medical clip sought to explain a bizarre event during the Franco-Prussian War. On August 6, 1870, at the Battle of Wörth in the Rhine Valley, a headless French horseman was spotted “going at full speed” across the battlefield. The Lancet’s explanation came out a month later on September 3.

Terre Haute Daily Gazette, September 29, 1870.

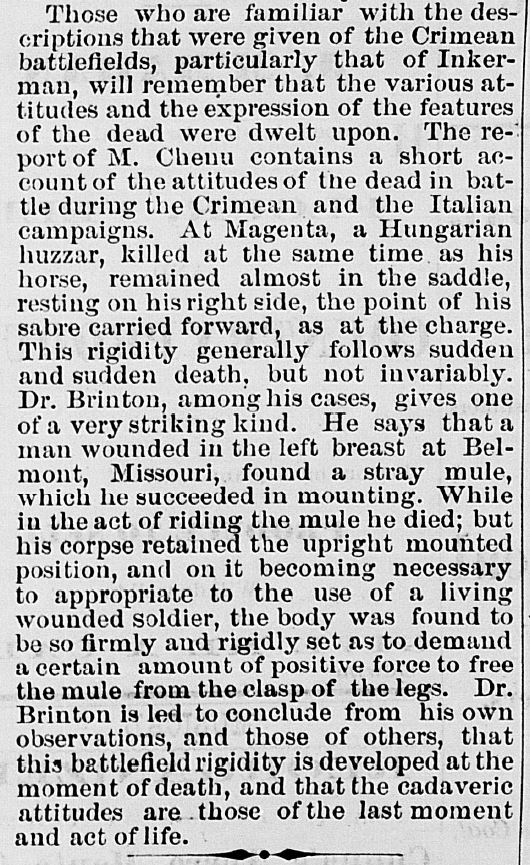

Terre Haute Daily Gazette, September 29, 1870.A letter to the editor sent as a follow-up and signed by Logan D.H. Russell appeared in the British magazine in January 1871. Dr. Russell gave a few examples of “life-like” rigidity in death witnessed by doctors, nurses, and soldiers during the American Civil War.

Scientific investigation into these aspects of post-mortem physiology continued during the 20th century. Though farmers and any homeowner with poultry in the back yard knew that “headless chickens” were no myth — the skeletal anatomy of chickens really do allow them to live briefly after decapitation — newspaper readers in 1912 were surely surprised to hear that a French surgeon in New York City had successfully performed experiments allowing headless cats to survive for another three days.

This surgical revolution was the work of Alexis Carrel (1873-1944), one of the more unusual and forgotten pioneers of surgery. Oddly, before he began experimenting on cats, Carrel’s scientific work took him into the realm of what most scientists consider superstition and folklore: divine healing.

Raised in a devout Catholic family, Alexis Carrel fell away from religion as a young medical student. In 1902, however, pressured by a colleague, he traveled to Lourdes in southwestern France to see something unusual.

Lourdes was a mountain town in the Pyrenees made famous in the 1850s by apparitions of the Virgin Mary, who allegedly came and spoke to a French shepherd girl there for weeks on end. French scientists and secularists, calling it a fraud, tried to have Lourdes shut down under public hygiene laws after thousands of suffering believers came in search of a cure — which, incredibly, they often found. For decades, reports of miraculous healings attributed to mineral waters from the caves and to divine intervention plagued, even embarrassed, European doctors and intellectuals.

In 1902, Alexis Carrel saw one of these miracles as it was happening: the sudden and complete healing of a tubercular patient given up for dead. Decades before the discovery of antibiotics, Marie Bailly, the patient, was soon declared totally free of her disease, which she was expected to die of at any moment. She became a nun and lived for another thirty years. Carrel, an agnostic, claimed that he actually watched her body undergo a healing transformation at Lourdes.

The young doctor delivered some of the main eyewitness testimony about the miracle — which led to his being banned from working in French hospitals and universities. With his reputation destroyed, Carrel emigrated to Canada, where he became a cattle rancher and farmer. Later coming to the U.S., he taught at the University of Chicago and the Rockefeller Institute in New York. Over the next few decades, Carrel became a pioneer in the field of vascular suturing techniques. Helped by aviator Charles Lindbergh, he invented the perfusion pump, used to preserve organs during transplantation.

For his work in human physiology — partly involving experiments on headless cats — Carrel won a Nobel Prize in 1912. Still baffled by the bizarre cure he witnessed at Lourdes, Carrel never retracted his belief that Marie Bailly was healed by a supernatural force, an event so strange that one writer believed it drove him mad. His book about the Lourdes miracle, written in 1903, was only published in 1949, five years after his death.

Science and religion both have their dark sides. Tragically, Carrel’s went beyond cutting up cats. By the 1930s, the French-American surgeon had become a major proponent of eugenics, the forced sterilization of “inferior” human beings and the poor. (Carrel was no pioneer here. Back in 1907, the Indiana Legislature instituted the world’s first eugenics law. Over 2,300 Hoosiers were sterilized in an effort to eliminate “degeneracy,” under a law only repealed in 1974.)

As a prelude to the Nazis’ perversion of science, Dr. Alexis Carrel went on to publish a bestselling book, Man, the Unknown (1935). The Nobel Laureate even joined an anti-Semitic French fascist party, the PPF. During Hitler’s occupation of France, Carrel helped put eugenics laws into place under the Vichy collaborators. If he hadn’t died in 1944, the doctor would probably have been put on trial as a traitor or war criminal.

All of which is further proof that scientists — like Hessian horsemen and everybody else — can lose their head.