The Lusitania disaster seems impossibly remote to some, but the great maritime tragedy occurred just a hundred years ago — within the living memory of our oldest citizens.

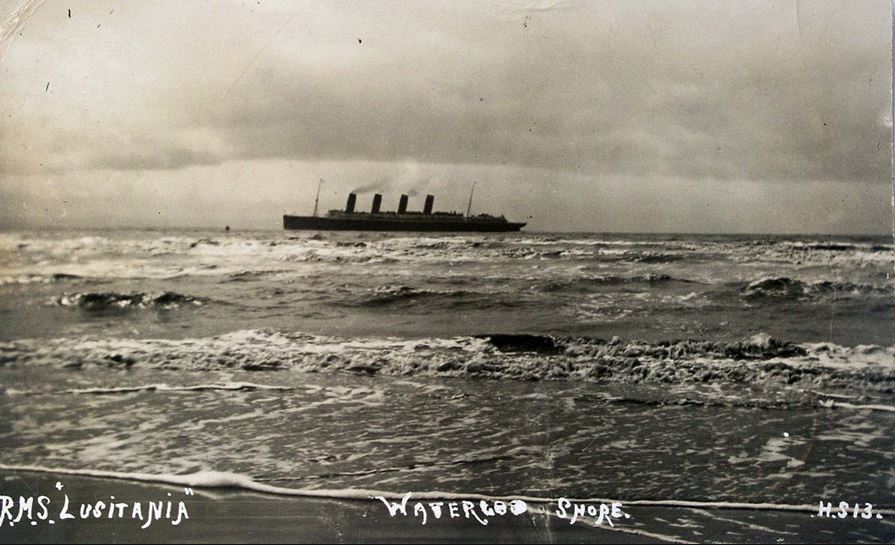

Photography was unable to capture the sinking itself. Torpedoed by a German submarine eleven miles off the south coast of Ireland on a beautiful May afternoon in 1915, the ship went to the bottom in just fifteen minutes, with the loss of 1,200 lives. Many still believe the ship’s unusually fast demise was caused by contraband explosives it carried in its hold, en route from the U.S. to Britain. If true, the Germans would still be guilty of a war crime, having fired the torpedo that ignited the illegal cargo, though the behavior of the British government, smuggling weapons on a passenger liner, would be hard to excuse.

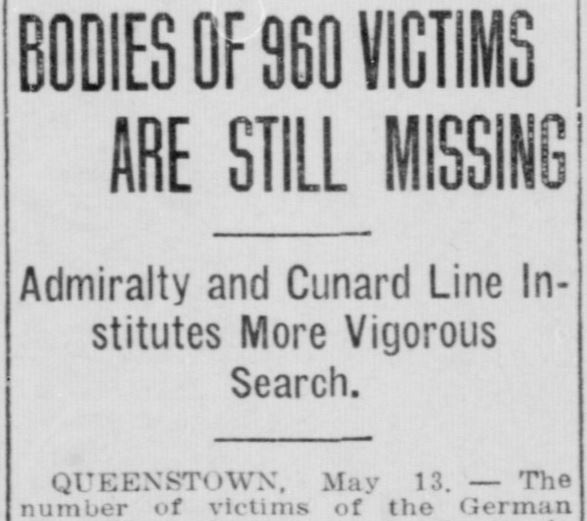

While the meticulous, body-by-body photographic record of the drowned victims is stashed away in the Cunard Line Archives in Liverpool, hundreds of the dead were never recovered at all. Others remained unidentified. A series of stark photos documented their burial in a mass grave in the town of Cobh (formerly called Queenstown) on Ireland’s south coast. Remarkably few American newspapers ever reprinted these somber photographs, which show a pile of old-fashioned “pincher coffins,” the kind that was beginning to go out of style in favor of modern, less “haunted-looking” caskets.

An exception was the Lake County Times in Hammond, Indiana, which published one of the gloomy images on May 25, 1915, almost three weeks after the sinking.

(Old Church Cemetery, Cobh, County Cork, Ireland, where 169 bodies from the Lusitania were buried.)

One of the anonymous victims who might lie in the Irish earth — but who probably went to the bottom of the sea — was a Hoosier man sailing aboard the doomed vessel.

Elbridge Blish Thompson was a promising 32-year-old sales manager from Seymour, Indiana, traveling to Holland with his wife Maude. Though Maude survived and went on to have a remarkable, unusual life, Thompson drowned and his body was never officially recovered.

Born in southern Indiana in 1882, Thompson came from a family of prominent millers who ran the Blish Milling Company, one of the main businesses in Seymour. Educated in Illinois and at the prestigious Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, Thompson went on to study at Yale, then metallurgy at the Sheffield Scientific School in New Haven. Popular at Yale, he defended his home state by saying “A man from Indiana can do no wrong.” In 1904, he married Maude Robinson of Long Branch, New Jersey. Thompson’s work as a metallurgist took the couple out to Breckenridge, Colorado, but after a few years, they came back to Seymour, where he took charge of the Blish Milling Company and the Seymour Water Company. It was the flour milling business that eventually led him to embark on a fateful trip to Holland in May 1915.

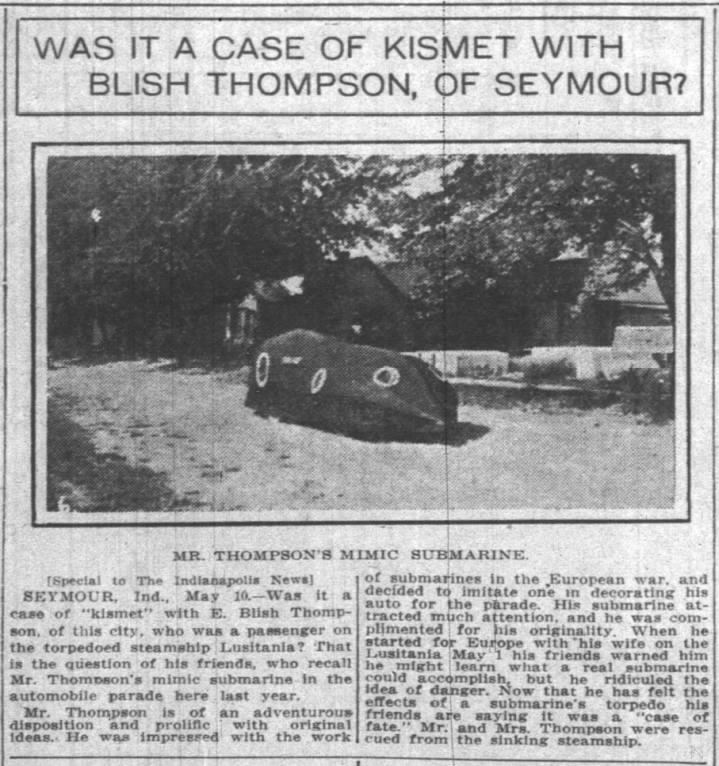

In 1914, a strange instance of what the Indianapolis News called “kismet” (fate) led Thompson to disguise one of his cars in a strange costume — as a German U-boat. The automobile was a blue National roadster built at the National Motor Vehicle Company in Indianapolis, a company headed by Arthur C. Newby, one of the founders of the Indianapolis 500. Three days after the Lusitania was torpedoed by a real U-boat, the News carried an almost eerie story about the “mimic submarine” that Thompson once drove through a parade in Seymour:

Mr. Thompson is of an adventurous disposition and prolific with original ideas. He was impressed with the work of submarines in the European war, and decided to imitate one in decorating this auto for the parade. His submarine attracted much attention, and he was complimented for his originality. When he started for Europe with his wife on the Lusitania May 1, his friends warned him he might learn what a real submarine could accomplish, but he ridiculed the idea of danger. Now that he has felt the effects of a submarine’s torpedo, his friends are saying it was a “case of fate.”

The News incorrectly reported that Blish Thompson had been saved. On the morning of May 15, he and Maude rose at 4:30 to watch the sunrise. That afternoon, they were in the first class dining room when the torpedo struck, signaled by a thud, then followed by a huge explosion that was either a coal bunker or a cache of illegal ammunition going off, the alleged contraband being smuggled to the Western Front which had led the Germans to target the ship to begin with. On deck, Blish gave his lifebelt to a woman. Unable to get into lifeboats as the ship lurched almost perpendicular, the Thompsons were swept down the deck and sucked into the water. Then the couple’s grasp was torn apart by the suction of the plunging vessel.

While a memorial service was held for Thompson in Seymour on June 18, his body never turned up. The stone monument in Seymour’s Riverview Cemetery was erected over an empty grave.

(Thompson’s memorial at the Riverview Cemetery, Seymour, Indiana.)

(Indianapolis Star, May 11, 1915.)

A more interesting fate than “Blish” Thompson’s is that of his wife. By the end of World War I, Maude Thompson had remarried, becoming one of that fascinating bunch of Americans who joined the European aristocracy. For years, Seymour — a humble Hoosier farm town — had a direct connection to France’s old nobility.

Widowed by the Lusitania disaster, Maude Thompson went back to Europe to volunteer with the Red Cross in France. On the boat with her this time, she brought not her husband, but Blish Thompson’s two automobiles — the National roadster he had disguised as a “mimic submarine” for the parade through Seymour and a National touring car. Maude donated these Indianapolis-built vehicles to the French cause. The re-outfitted roadster served as a scout car on the Western Front. The touring car was given to the Red Cross. During World War I, Maude met and fell in love with an ace French fighter pilot, Count Jean de Gennes (pronounced “Zhen.”) Although she was twelve years his senior, the two were married in Paris in November 1917.

(Count Jean de Gennes, second husband of Maude Thompson, served in the French air force and transatlantic air mail service. His son was born in Seymour, Indiana.)

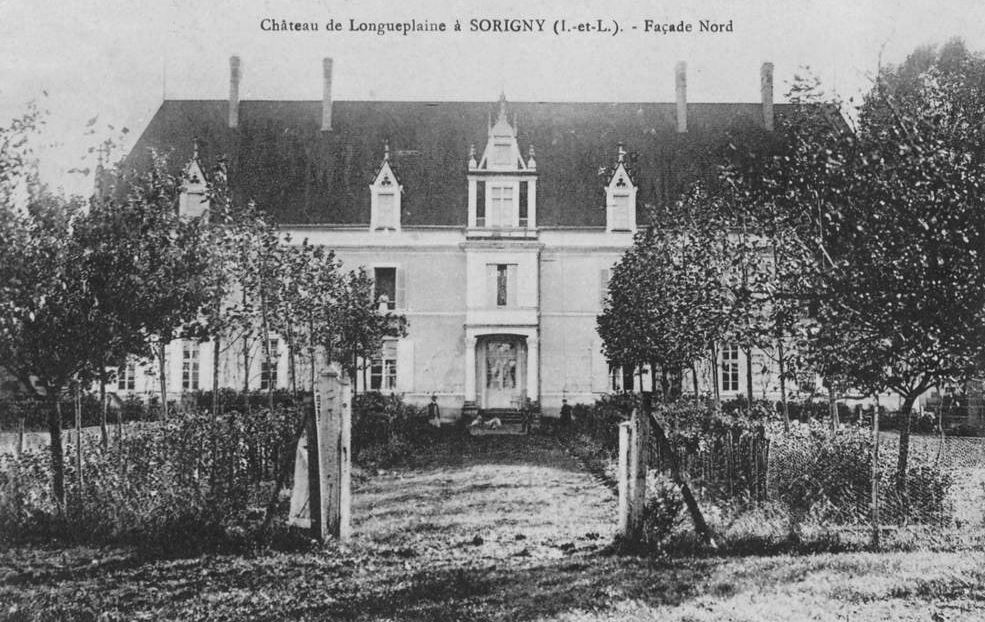

After the Allied victory over the Germans, the new Countess de Gennes moved to her husband’s spectacular Loire Valley estate, the historic Château de Longue Plaine, located 30 miles south of Tours in western France. It was a fairy-tale twist to a marriage due in part to the deadly sinking of the Lusitania. Their son, named after his father, was born in 1919 while his mother was on a visit back home to Seymour, where she served on the board of the Blish Milling Company. The young Indiana-born count would later serve during World War II as a pilot in the French Resistance, also flying in night-time bombing raids over Germany with the R.A.F.’s Bomber Command.

Maude’s husband was often away from home. During the 1920s, Count de Gennes was one of the great pioneer airmail pilots, navigating the dangerous South American and North African routes between France, Casablanca, and Buenos Aires. One of his colleagues at the Compagnie Aéropostale was the great French pilot and novelist Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, author of The Little Prince and several great early non-fiction classics of flight. Like Saint-Exupéry, who vanished into the Mediterranean during World War II, Count Jean de Gennes — member of the French Legion d’Honneur — died in a plane crash off the coast of Morocco in 1929.

Six years before the count’s death, an unnamed reporter from the Indianapolis News paid a visit to the de Gennes family at their sprawling chateau near the Loire.

As the Hoosier reporter described it, Maude — “a former Indiana woman” — had refurbished much of the old 17th-century castle, which had been revamped in the early 1800s but originally dated back to the Middle Ages. Maude installed its first electric lights, a central heating system to replace “big hungry-mouthed fireplaces,” and put in a power plant out back. She also brought over bits of the Hoosier State with her, incorporated into the house or stowed away.

It was a delightful experience to live in this charming old place in the midst of American furniture — for the complete contents of the Seymour home had been transported to France. . . While it may seem like carrying coals to Newcastle, to take our furniture to a country famous a thousand years for its beautiful cabinet work, the old Indiana bureaus and tables and other pieces fitted admirably into the delightful old French setting. . .

Baby Jean lives in a suite of his own that was all paneled and cupboarded with Indiana wood. Even his furniture was built from Indiana lumber.

Much of this wood from Jackson County is probably still there today.

The reporter also found. . . Indiana newspapers:

(Château de Longue Plaine, where Maude Thompson lived into the 1940s.)

(Hoosier-born French pilot Count Jean de Gennes served as a bombardier in the “Groupe Guyenne,” a segment of the R.A.F.’s Bomber Command that flew out of Tunisia and Britain, carrying out the controversial night-time raids over German cities that killed thousands of civilians. Half of the squadron itself died in action.)

(Hoosier-born French pilot Count Jean de Gennes served as a bombardier in the “Groupe Guyenne,” a segment of the R.A.F.’s Bomber Command that flew out of Tunisia and Britain, carrying out the controversial night-time raids over German cities that killed thousands of civilians. Half of the squadron itself died in action.)

Though she could easily have found refuge in the U.S., the Countess de Gennes stayed in France during the Nazi occupation of her adopted country. In 1946, she moved to New York City with her son, who was working for Air France. Maude lived out her remaining days in Queens. She died on May 17, 1951. According to her last wishes, she was buried in France.