Nineteenth-century American newspapers overflowed with medical ads. Many touted quack panaceas, remedies for everything from dropsy and tuberculosis to STDs and impotence. At a time when even “scientific” medicine was often little better than the variety promoted by “snake doctors,” folk medicine and spurious innovators actually helped keep newspapers afloat — as underwriters paying for ad space.

Six years before the Civil War broke out, the editors of the Brookville Indiana American put in some clever medical commentary. Rather than feed your kids candy — a potential medical and dental no-no — why not buy them “toy books,” ancestor of the “pop-up” book?

(Brookville Indiana American, August 31, 1855.)

A few months later, candy sales must have still been trumping sales of movable toy books at Dr. Keely’s. The editors reissued their advice: buy your kids candy for the brain, not sugary venom that “injures the health.”

(Brookville Indiana American, February 8, 1856.)

(Brookville Indiana American, February 8, 1856.)

Was this the dry, brutal utilitarianism of Charles Dickens’ Thomas Gradgrind? (The satiric Hard Times, which included an overbearing schoolteacher named M’Choakumchild, came out in 1854.)

Now, what I want is, Facts. Teach these boys and girls nothing but Facts. Facts alone are wanted in life. Plant nothing else, and root out everything else. You can only form the minds of reasoning animals upon Facts: nothing else will ever be of any service to them.

What were these “toy books,” competitors of the sugary destroyer?

Modern readers might imagine that the movable revolution in children’s literature is a new phenomenon. Yet the earliest books incorporating retractable parts date back to the 13th century. Spanish philosopher Ramón Llull, who tried to demonstrate God’s existence through numerology, put spinning paper wheels in his books. These helped the reader understand the mathematical charts illustrating Llull’s theories about the universe as a thinking machine.

Cosmologists’ use of movable book parts was complemented by Renaissance-era medical men. One example was Dutch doctor Andreas Vesalius’ De humani corporis fabrica (On the Structure of the Human Body), printed in Switzerland in 1543. Readers of this anatomical manual could lift flaps covering Vesalius’ illustrations to get a peak at the human innards and even watch a child being born.

Eighteenth-century London publisher Robert Sayer made a different kind of “interactive book.” Around 1765, Sayer was making books with movable flaps revealing the “inside story” of everything from children’s tales and folk ballads to the story of Adam and Eve and the metamorphoses of Harlequin, a stock character in Italian comic theater. Sayer’s “Harlequinades” were hugely popular in England and Europe. Some must have showed up in colonial America.

(Robert Sayer, Harlequinade of Adam & Eve, circa 1770. A short history of the origins of death.)

By the 19th century, book makers were taking movable illustrations even further. In England, Stacey and William Grimaldi published a title in 1821 called The Toilet Book or just The Toilet. The Grimaldis — father and son — promoted the traditional idea that feminine beauty was a mark of virtue. (“Toilet” referred to beautification, washing, and maintaining one’s health at a time when poet John Keats emphasized that “Beauty is truth, truth beauty.”) The Grimaldis’ illustrations of mirrors, perfume bottles, etc., could be lifted up to reveal fortune-teller-like revelations.

In addition to “peep show” and “tunnel” books — paper cut-outs depicting theater scenes — some of the best-known and most successful examples of the “interactive book” before the Civil War were those of Dean & Son, English publishers. These were probably available at Hoosier bookstores before the Civil War — copies were advertised for sale in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1860. Paper images were connected to paper tabs that, when levered back and forth, moved the cut-out characters around the page or flipped the entire illustration over to reveal a development in the story.

One of the Deans’ most popular titles was Dissolving Views. A kind of 3-D forerunner to the stereoscope, which allowed readers to travel to places they would never see in person, some of its illustrations showed exotic landscapes, such as volcanoes erupting — succeeded by fire’s elemental opposite, cascading water. Others depicted folktales or comic scenes with a didactic message.

(Dissolving Views, publishing house of George Dean, London, 1862.)

(Dissolving Views, publishing house of George Dean, London, 1862.)

With the invention of cameras, improvements in optics, and the advent of more sophisticated magic-lantern projectors (first developed in the 1650s), “dissolving views” became a synonym for early, “phantasmagoric” versions of the cinema. During the days of Dickens, these motion pictures were big entertainment. Eventually, they evolved into silent film.

(The Times-Picayune, New Orleans, Louisiana, February 21, 1841.)

(The Times-Picayune, New Orleans, Louisiana, February 21, 1841.)

(Indianapolis News, November 2, 1870.)

Contemporary newspaper advertisements show that several Hoosier booksellers stocked “toy books” in the mid-1800s. Unfortunately, they don’t list the titles. Yet as Brookville’s Indiana American shows, as early as 1831, just fifteen years after Indiana achieved statehood and with much of it still wilderness, even small country towns had access to these children’s books.

In Lawrenceburg on the Ohio River, toy books were sold alongside such things as thermometers, spy glasses, tooth picks, mustard seed, cough drops, and… tweezers:

(Lawrenceburg Western Statesman, January 7, 1831.)

(Lawrenceburg Indiana Whig, January 25, 1844.)

(Lawrenceburg Indiana Whig, January 25, 1844.)

(Brookville American, December 24, 1858.)

(Brookville American, December 24, 1858.)

(Evansville Daily Journal, December 18, 1852.)

(Richmond Dispatch, Richmond, Virginia, December 23, 1859.)

(Daily Evansville Journal, December 25, 1862.)

(Daily Evansville Journal, December 25, 1862.)

In December 1868, a weary Indianapolis father trudging home in “a half dreamy state” after fifteen hours “at the office” was surprised by a man standing on his roof when he got home. Santa Claus, whom he insulted as “You confounded Dutch idiot,” was greeting him with a “Hi! Hello! Stop! Hold on!”

Santa showed the man a sneak preview of what he was bringing his children. This windy story — in reality, an ad for Indianapolis’ Bowen, Stewart & Co. — might rank as one of the longest ads for a bookstore in the annals of American journalism. Fortunately, Santa wasn’t hauling around a bag-load of candy:

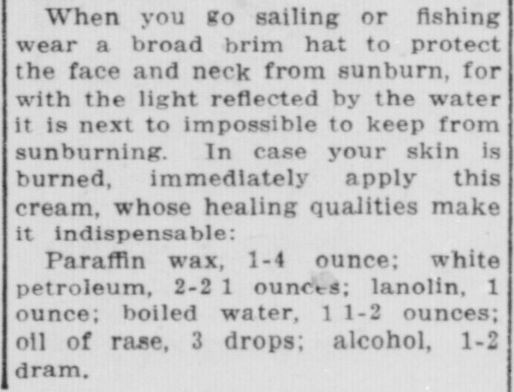

South Bend News-Times, May 19, 1920.

South Bend News-Times, May 19, 1920.