“The most damnable spot in America.” “A disgrace to civilization.” “Filth and abomination.” “Indiana’s Black of Hole of Calcutta.”

The Hoosier State sometimes get bad national press, but in 1923 the criticism was homegrown. True to Hoosier stereotypes, the alleged horrors took place on a farm, the state penal farm, and involved the abuse of prisoners.

On the eve of World War I, a new, “open-air” penitentiary opened about an hour west of Indianapolis. Overcrowding at the major state prisons in Michigan City and Jeffersonville, as well as at county jails all over Indiana, led the legislature to pursue a “progressive” alternative to mere incarceration. Many prisoners, after all, were behind bars for minor crimes like theft and assault and battery. That changed in 1917, when Indiana Governor James Goodrich initiated statewide Prohibition, two years in advance of the Federal liquor ban that came with the Volstead Act in 1919.

Since some Indiana counties and towns had already passed local dry laws, by 1915 sheriffs were cracking down on operators of illegal saloons, moonshine distillers, and town drunks. While most violators were never tossed in the clinker for more than a few weeks or months, as the war on alcohol got more serious, Hoosier jails began to fill up fast. The temptation to make a profit off jails was a further problem, a situation that still exists today.

Prohibition laws provide a fascinating glimpse into the dark side of reform movements. As one Hoosier editor, Muncie’s George R. Dale, discovered while investigating allegations of prisoner abuse at the State Farm in Putnamville, punitive social reform — including the ban on alcohol sales — had scarcely hidden undertones of racism and class operating behind it. Working-class Americans, African Americans, and Catholics bore the brunt of laws framed mostly by women’s rights advocates and middle-class white Protestants. Liquor laws, oddly enough, turned out to be a major milepost on the intellectual superhighway that led to the resurrection of the Ku Klux Klan in 1915 — coincidentally, the year of the penal farm’s founding. The original Klan had died off in the 1870s. Revived just before Word War I, it found its highest membership not among stereotypical rural Southerners and defeated Confederates, but among white middle-class Midwesterners. The ideology of “the second Klan,” moreover, wasn’t totally foreign to the reform movements of the 1910s.

In 1922, Dale, a civil liberties maverick, joined the campaign to investigate the penal farm — then went there twice as a prisoner, sentenced to hard labor for criticizing a Delaware County judge with Klan connections.

Though the farm would soon fall under suspicion, the plans behind its creation were full of good intentions. Jailers and prison reformers had always been vexed by the failure of jail sentences to cure some criminals of their attraction to lawbreaking. The theory was that inmates were bonding behind bars while living in “idleness.” As a Hoosier paper, The Hagerstown Record, put it in 1916,

Jails are simply breeding places for vice. Lawbreakers thrown together in sheer idleness day after day have opportunity and incentive for devising more lawlessness. The hardened men create an atmosphere of viciousness that influences the less hardened, while the shiftless vagrant finds very little punishment in free board and no work.

Penal labor, though not wrong in itself, had an enormously dark history — from Charles Dickens’ hellish “workhouses” in David Copperfield to British convict colonies in Australia and of course the Siberian gulags of Tsarist and Soviet Russia.

A 1913 law passed by the Indiana legislature made possible the establishment of a pioneering state penal farm. That law appropriated $60,000 for the purchase of at least 500 acres of land. To help prevent party control and graft, the bipartisan committee, like the prisoners themselves, would receive no salary for their work.

The committee eventually bought 1,600 acres around Putnamville, five miles south of Greencastle, in a hilly, rocky part of Putnam County. Much of this acreage was considered “too broken for agriculture.” Yet this didn’t put a halt to plans, since the penal farm would include several industries besides farming. Underlain by Mitchell limestone, prisoners were put to work breaking rock in quarries, used for road building and the production of crushed limestone fertilizer used on fields. Prisoners also sawed lumber from a neighboring forest reserve. Additionally, the farm kept a dairy herd, apple and peach trees, and fields that grew corn, hay, soybeans, sorghum, pumpkins, and tobacco (a crop now practically extinct in Indiana). In 1916, the prison kept 190 “fat and sleek” hogs. Most of this produce went to fed patients and staff at state hospitals.

A brick plant came in 1918, with prisoners turning out 30,000 bricks a day. The bricks were used in the construction of a new medical college and a military warehouse in Indianapolis and of the Indiana Village for Epileptics, later renamed the New Castle State Hospital. (This happened at a time when epileptics were considered a menace to society and segregated. Indiana’s 1907 eugenics laws forbade epileptics to get married, putting them virtually in the same class with criminals subjected to forced sterilization.)

The money-making possibilities of the state farm were already stirring up buzz among citizens of Putnamville, an old pioneer town on the National Road that nearly became a ghost town when the Putnam County seat was moved to Greencastle. The Indianapolis News reported that rumor of the farm’s coming “spread over the hills and valleys like wildfire” and that residents believed it would “make the old village glow with new life.” “Friends of prisoners” and “sightseers” will “come and go and Putnamville will thrive on the nickels and dimes they spend.”

Locals didn’t seem worried about having prisoners as neighbors, though the penal farm was barely guarded at all. Punishment for escaping was apparently considered enough of a threat to deter the attempt. Fugitives from the law would find their sentences, sometimes a mere 90 days, extended to two years in a state prison if caught.

Newspapers give insight into the type of criminal sent to the State Farm. After Indiana’s prohibition law was ratified in 1917, more than half of the prisoners here came on liquor-related offenses — whether running a “blind tiger,” a rural whiskey still, or being drunk in public. Although bootleg whiskey could be very deadly, other prisoners were jailed for the slimmest of crimes. One was an 18-year-old from Indianapolis who stole a penknife.

The Indiana State Penal Farm’s bleak reputation wasn’t long coming. Less than a year after its founding, John Albright, a bootlegger from Terre Haute, actually requested deportation to his native Germany during the height of World War I rather than serve 90 days at the farm.

Newspapers also documented escapes from the farm, a few of them dramatic. In 1916, two prisoners who drove farm horses ran away with their steeds. They tied them to trees in the woods around Greencastle, where the animals were later found starved to death, “tethered a few paces from an abundance of grass and water.” A year earlier, two Indianapolis youths escaped, went on a burglary and horse-stealing spree near Terre Haute, and were then hunted down by a posse of Vigo County farmers. When four men escaped in 1917, including an African American from Lake County, a “sensational gun fight” ensued. The African American, a man named Hall, was shot dead.

In May 1915, just a month after opening, there were 217 prisoners living at the farm, including 30 African Americans. The total number that skyrocketed to almost 1,200 within a year. In its first decade, the farm “entertained” about 25,000 prisoners.

In 1920, a controversy broke out over allegations of cruelty at Putnamville. Charles McNulty, an Indianapolis saloon keeper let out on parole, filed a complaint with the State Board of Health. McNulty’s claims about unsanitary conditions and violence were backed up a year later when Oscar Knight, a prisoner, filed a further complaint with a judge. Knight claimed that jailers served inmates food that “is not fit for hogs.”

McNulty alleged that prisoners were routinely underfed and worked ten hours a day at hard labor. Meat was only served once a week, “one slice of fat bacon,” less than what prisoners at other jails got while merely sitting in a cell.

Musty meal was used for making corn bread three times a week until Putnam County health officers forbade the use of it. . . On Sunday, five crackers is the substitute for the dry bread of weekdays. Some of the paid guards are insulting and cruel and inhuman, especially to cripples and weaklings, using a loaded cane to beat them.

There were further allegations that Governor Goodrich’s family and “hirelings” of his administration profited from unpaid labor, since inmates at Putnamville were “farmed out” to the Globe Mining Company, partly run by the governor’s son. Charles E. Talkington, superintendent of the penal farm, blew these charges off by claiming that McNulty was a member of the International Workers of the World (IWW) or “Wobblies” Talkington had previously been head of the Farm Colony for the Feeble-Minded in Butlerville and Bartholomew County’s school superintendent. The “Feeble-Minded Farm” — also called the Muscatatuck Colony — was, like the epileptic “village” in New Castle, part of Indiana’s dark eugenics campaign, which blamed crime on mental retardation and figured into a backlash against immigrants and the poor.

Yet early charges made about the farm were tame compared to those reported in one of the most fiery and flamboyant Hoosier newspapers Dale’s Muncie Post-Democrat.

Dale had just begun a landmark battle against the Ku Klux Klan. Though the Klan almost took over Indiana government in the 1920s, it was rooted in years of corrupt politics and arguably even social reform movements like Prohibition and eugenics. During his long battle to expose the Muncie Klan, Dale would be attacked by gunmen who tried to shoot him and his son. Yet the white-haired editor took on the Klan with humor, writing outrageous lampoons about “Koo-Koos” and “Kluxerdom” in his weekly paper, which was almost wholly dedicated to ridiculing the Invisible Empire. Dale published lists of known or suspected Klan members. He also grappled with the KKK’s powerful women’s auxiliary at a time when thousands of Hoosier Klanswomen spread hatred through families in ways that their male counterparts actually had less success at in their public roles. Dale vocally supported blacks, Jews, Catholics, and immigrants, and anybody else targeted by the Klan.

In August 1922, Dale also came to the defense of prisoners at the State Farm. The battle would go on for years. Before it was over, he got a chance to see the terrors of the “Black Hole of Indiana” up close. For criticizing a Muncie judge with links to the Klan — Clarence Dearth, a man he called “the most contemptible chunk of human carrion that ever disgraced the circuit bench in the state of Indiana” — Dale was sentenced for contempt of court and libel, fighting a four-year-long legal battle to stay out of the farm himself. Dale’s campaign is an overlooked part of the history of freedom of speech in Indiana.

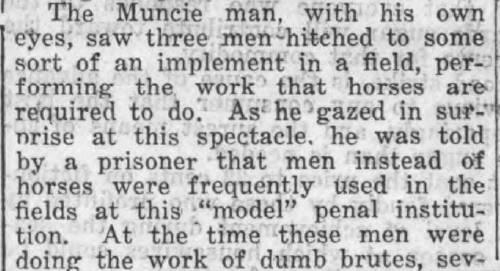

His first jab came on August 4, 1922. That story was based on the accusations of “a man from Muncie” who had just visited Putnamville. (Dale doesn’t give his name.)

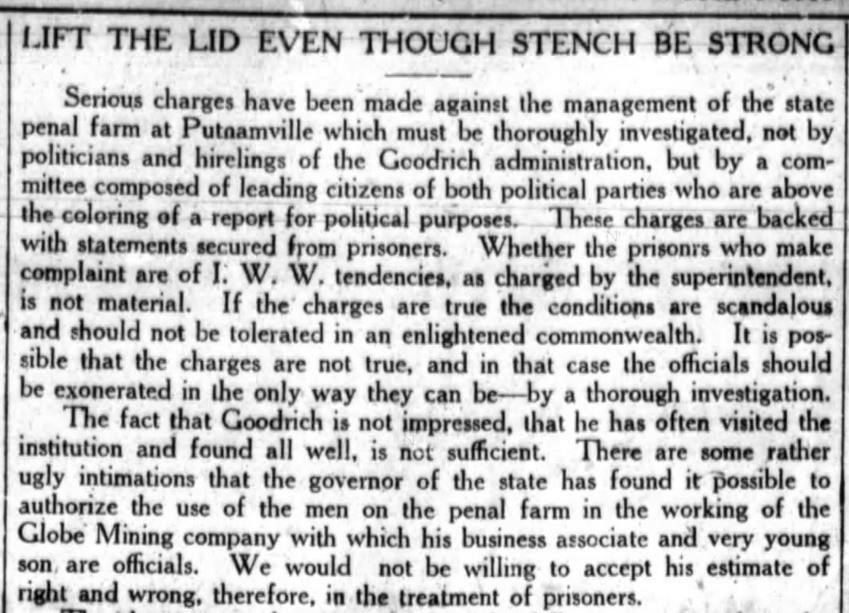

Muncie Post Democrat, August 4, 1922. Hoosier State Chronicles.

Muncie Post Democrat, August 4, 1922. Hoosier State Chronicles.When Dale criticized a libel ruling Dearth, the judge handed him a 90-day sentence at Putnamville. After eleven days in a Muncie jail, the editor entered the State Farm’s gates as “Convict 14,378.” Partly through the efforts of his wife Lena, the Indiana Supreme Court ordered Dale’s release after just three days. He now had a chance to write “from actual experience”, not the reports of others. Dale immediately set to work “serving notice on the Ku Klux Klan and its miserable tools in office.”

While wealthy bootleggers and Prohibition violators with connections in government often got off scot-free, Dale wrote that when he went to Putnamville, he stood in line with working-class men.

Stepping into the prison barber’s, “in exactly ten seconds my head looked like a billiard ball.” The 56-year-old and father of seven claimed he was then forced to strip down and shower in public, received filthy clothes that “smelled like sin,” got sprayed down by a fruit-tree sprayer, and was vaccinated by a veterinarian. Of the eight meals he ate in the mess hall in the course of three days, he never got any meat. He slept in a miserable, freezing dormitory with 204 other inmates, most of them sick and packed in “like sardines in a can.”

Dale insisted that many of these inmates were jailed on trivial liquor charges. He described one man whose family was left subsisting on charity while he rotted at the farm for almost two years, “having no money to pay his fine,” though prisoners were supposed to receive $1.00 a day for their labor. Always keen to publish news about the discrepancies in punishment meted out to African Americans versus whites, Dale mentioned black teens at the penal farm sentenced for bicycle theft and other minor offenses.

The editor put out an appeal to Governor Warren Terry McCray to investigate the “Putnamville Disgrace.” While he commended the governor for investigating similar jail horrors in Marion County and at the new Indiana Reformatory in Pendleton, Dale insisted on “The Difference Between Men and Bulls.” Cattle on McCray’s bull farm near Kentland lived better lives than prisoners at Putnamville, he announced. Taking heed of these accusations, Dr. James Wilson, mayor of Wabash, Indiana, refused to send any further offenders to Putnam County “until that place of horror is changed from a torture pen into a place of punishment where convicts are treated like human beings instead of dumb brutes.”

In 1926, two years after Ed Jackson, a Klansman, became Governor of Indiana, Judge Dearth and editor Dale were still fighting. Dearth sent the newspaperman back to the penal farm once more when Dale continued to ridicule him. Dale was also found guilty on a “trumped up” charge of liquor possession and of libeling George Roeger, a Muncie distributor of D.C. Stephenson‘s newspaper, The Fiery Cross (printed in Indianapolis). Dale had accused him of being a “Ku Klux draft dodger.”) A jury allegedly packed with Klansmen also declared him guilty of carrying a concealed weapon. Dale appealed the case to the Indiana Supreme Court but lost. Judge Julius C. Travis wrote the opinion that “the truth is no defense” and that Dale had held the law up to ridicule. Newspapers in Chicago and elsewhere started a defense fund to support freedom of speech.

In July 1926, Dale spent a further nine days at Putnamville, digging a tile ditch. He was released, strangely enough, by order of Governor Jackson himself. He got another sentence in August 1927, but spent just half an hour there. It was enough time, however, for him to be fingerprinted and booked as a convict. He also described a conversation with a young African American, James Martin, sentenced to six months for stealing $5.00. Martin had a wife and three children.

Judge Clarence Dearth of Muncie was later impeached. George Dale went on to become Muncie’s mayor from 1930 to 1935. As editor and mayor, he kept an eye on corrupt judges and police.

The Indianapolis Times began a series of articles about abuse allegations that continued to come out of the Indiana State Penal Farm. Yet the farm survived, receiving many inmates throughout the Depression. Most came on charges of larceny, liquor offenses and issuing fraudulent checks. Some, though, were guilty of more serious crimes, like drunk driving and child molestation. Still others came for downright strange reasons, like a Kendallville man arrested for selling “fake radium belts” for which he claimed curative powers. Then there were the sentences that now seem downright cruel.

Heavy drinkers were packed off to Putnamville into the 1950s. Through the 1960s, inmates milked cows, tended an orchard, and grew vegetables, also raising 18 acres of tobacco. About 40 convicts a year escaped in the 1970s and ’80s. Staff and guards were unarmed.

In 1977, the farm was reclassified as a medium-security prison and began receiving convicted felons, which partly contributed to the decline of farming there in the 1980s. The State of Indiana later tried to revive dairy farming at Putnamville in the 1990s. In 1995, the prison was operating the largest dairy farm in the county. Yet of the farm’s 1,600 inmates that year, less than 100 were working in agriculture.

Conditions in the mid-’90s had definitely improved since the days of Prohibition. The Kokomo Tribune reported in 1994 that 900 gallons of food scraps a day were being taken from the dining hall, mixed with cow manure, and used in a composting initiative. That project cut the prison’s garbage bill in half.

Now called the Putnamville Correctional Facility, the institution survives. Almost 2,500 prisoners are there today, more than at any time in its history.

Contact: staylor336 [AT] gmail.com