Cooties aren’t what they used to be. When I was a kid growing up in the long-lost 1980’s, cooties were imaginary germs — and not something you usually wanted. If you accidentally came into exposure with these fictitious microbes, quarantine wasn’t necessary, though you might get socially ostracized for a day or two. In fact, that was kind of the point. In the worst-case scenario, however, unless you were a perennial cootie hatching ground, you could just rub the little critters off onto somebody else. One definition even calls cooties an “infection tag game.” The dark side, of course, is the mild sexual harassment hovering over elementary school playgrounds. And yet. . . some cooties you actually want. Without these benign cousins — love germs — life might not even be worth living.

Early Clinton-era cooties, though, weren’t the kind that an earlier generation of Americans knew. A senior colleague of mine at the Indiana State Library has just testified that the psychological variety of this make-believe organism has been around since at least the 1950s. Yet its pedigree dates even farther back than that.

Cooties, in fact, were being mentioned in American newspapers as early as 1918. The ancestral cootie? Like most of us, it seems to have had immigrant roots. As far as journalists knew, this was an annoying variety of lice that proliferated in the trenches of Europe during World War I.

Were cooties immune to warfare? Maybe, maybe not. The writer was probably joking here, and might have been telling a big tall tale, but it sounds like one way to get rid of the bug was to give it a good jolt:

Captain Charles W. Jones, a teacher at Greencastle High School who served on the Western Front, told a Putnam County audience in 1919 about his uncomfortable experiences in France. Alongside the perils of bombs and poison gas. . . the little bug called cooties:

Etymology meets entomology at the Oxford English Dictionary, whose talented word-sleuths think “cootie” might come from the Malay word kutu, denoting a parasitic biting insect. Except for one minor naval battle, World War I wasn’t waged in Southeast Asia, so unless Malaysian troops fighting in Europe coined the word, its passage into English is actually quite mysterious.

Yet soon, cooties were coming to America in letters: literally!

That was good news for the Netherlands, which wanted to get rid of them:

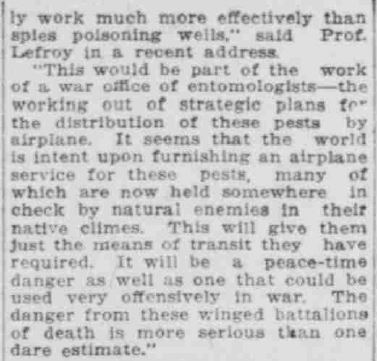

In the event of the next global war — and in an eerie parallel to chemical warfare — the (perhaps mad) English entomologist Harold Maxwell-Lefroy was actually looking at ways to disseminate deadly diseases behind enemy lines by means of propagating mosquitoes, house flies. . . and — get this! — cooties.

South Bend News-Times, May 19, 1920. Hoosier State Chronicles.

South Bend News-Times, May 19, 1920. Hoosier State Chronicles.In fact, the tiny foe looks disturbing enough:

By the early years of the Jazz Age, these pestiferous creatures had apparently made it “over here” on the backs, in the clothes, and probably in some of the doughboys’ uncomfortable nether regions.

Up in Cadillac, Michigan, folklore, at least, thought the Kaiser’s cooties were refusing to recognize the Armistice and were carrying on the war against American grasshoppers undismayed:

Even venomous snakes, it was believed, got laid low by the dreaded bug:

The New York Tribune thought these lice should have figured into the staggering death toll of the so-called “War to End All Wars.”

Around 1919, somebody invented a children’s board game. I have never played this game, but according to one description, you put two pill-like objects with BB’s inside a box painted like a World War I battlefield. A cage — sometimes with a fox hole underneath it — sits at one end of the box. The challenge is to maneuver the “cooties” over the mine-infested field of death and dispose of them inside the cage.

In 1920, this game was being manufactured by the Irvin-Smith Company of Chicago, who touted it as “good for your nerves.”

The Cootie Game was offered for sale at George H. Wheelock’s department store in South Bend in 1919:

Having cooties on you, however, was no game, and is a genuine part of American medical history.

One solution for the lice was a “liquid fire” called P.D.Q., possibly manufactured at Owl Chemical Company in Terre Haute, Indiana. The initials were said to stand for “Pesky Devils Quietus.” Wherever it was made, the squirtable cootie-killer was on sale in Hoosier drug stores not long after the end of World War I. It sold for the same price as the Cootie Game: 35 cents.

What the exact difference is between cooties and the domestic American chiggers, I’m not sure — and nobody seems to have checked into hospitals recently complaining of cooties. Sometime around 1950, apparently, these bugs evolved into a mildly harmless children’s phobia.

The cootie’s association with war did, however, survive. In 1920, a service organization affiliated with the VFW was founded in New York City — the Military Order of the Cootie. Though no World War I vets are around to tell us about scratching and the other horrors of trench warfare, the order — devoted to community service and, just as importantly, to humor — is still active to this day.

We salute the Cooties!