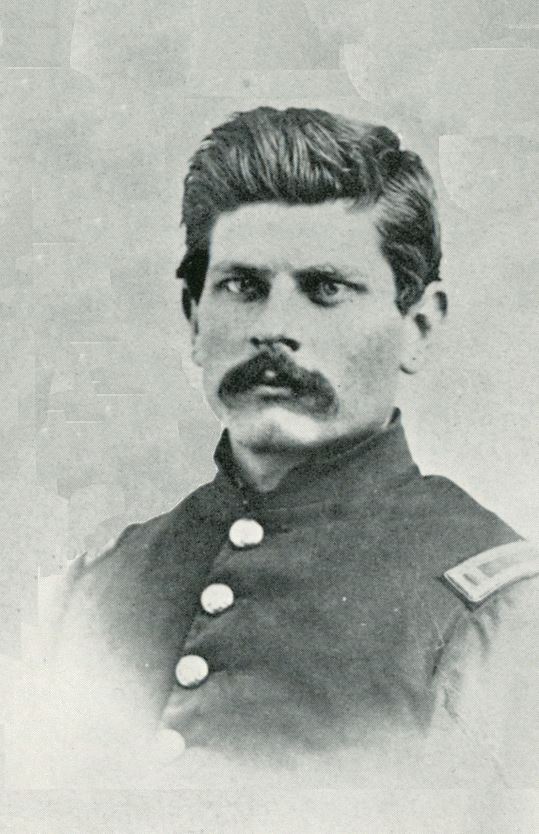

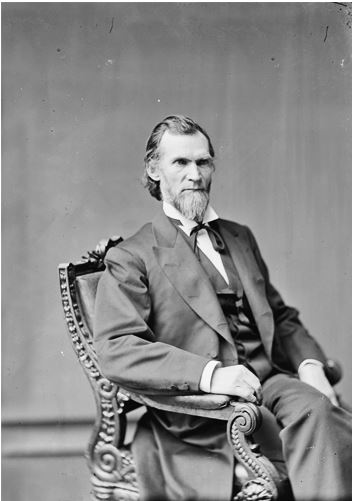

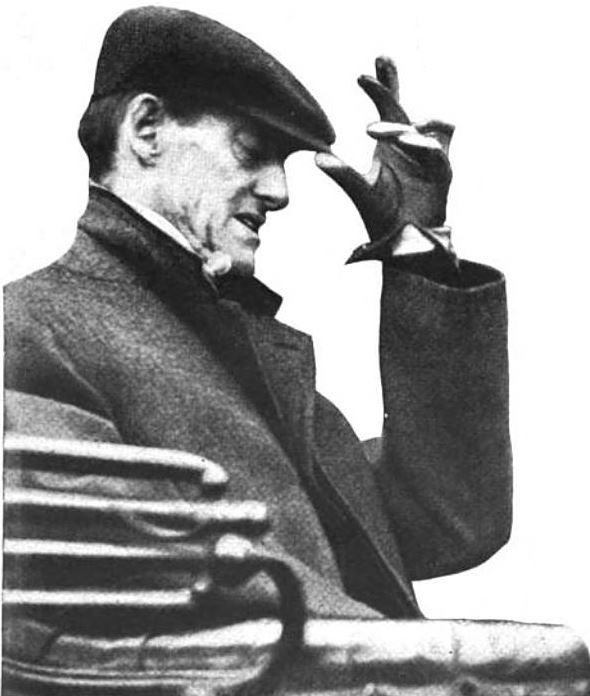

In the early 1880s, Indiana’s great novelist and war hero, General Lew Wallace, author of the bestselling Ben-Hur, got caught up in one of the more trumped-up tales of nineteenth-century journalism — a story which, it turns out, has an incredibly bizarre “cousin” today. The mildly erotic tale begins around 1883, when Wallace was a well-known American public figure. To quickly recap his bio: son of Governor David Wallace of Indiana, the “militant romantic” had served in the worst battles of the Civil War; sat on the trials of the Lincoln conspirators and Henry Wirz, the Swiss-born Confederate commander of Andersonville prison; fought as a Juarista general in the Mexican Army during the French invasion of 1865; and as Territorial Governor of New Mexico, he helped reign in the outlaw Billy the Kid.

Slowly propelled to greater fame when the novel Ben-Hur came out, Wallace went to Constantinople in 1881 as U.S. Minister to the Ottoman Empire. The general and his wife, writer Susan Wallace, were ardent Orientalists. Yet Ben-Hur, set in Palestine, was published a year before they ever saw the Middle East, its description based on research in the Library of Congress. The couple traveled around the eastern Mediterranean.

During his four years as an American diplomat in Constantinople, the Hoosier writer became close friends with Ottoman Sultan Abdül Hamid II — though Wallace famously became “the first person to demand that the sultan shake his hand.” When Grover Cleveland was elected U.S. President in 1884, Wallace’s term ended. Abdül Hamid tried to get his friend to stay on and represent Turkish interests in Europe. Wallace, instead, came home to Montgomery County.

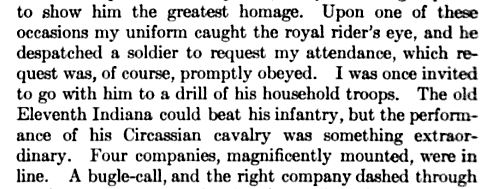

(Lew Wallace described watching a Turkish infantry and Circassian cavalry drill with the Ottoman Sultan in his Autobiography, published in 1906.)

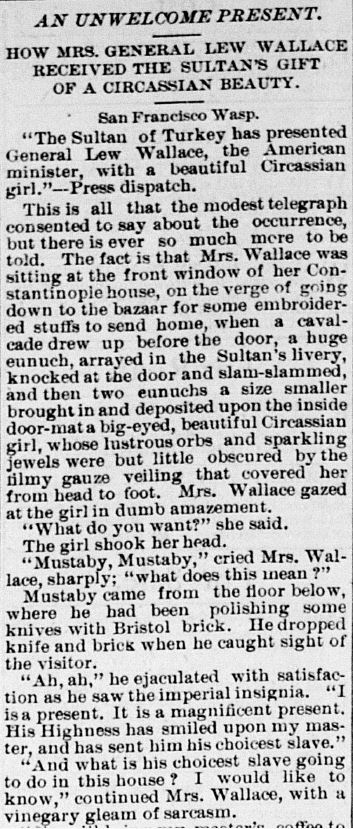

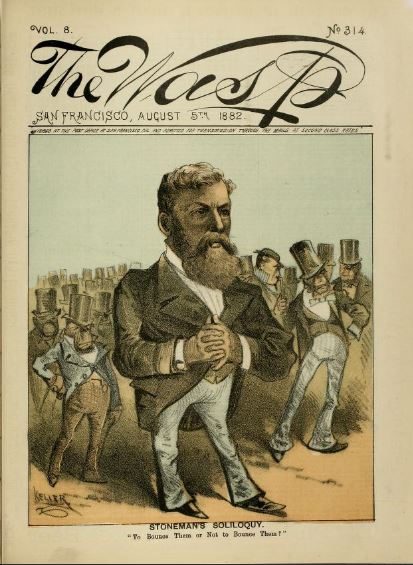

The gossip mill, however, was already rolling years before Wallace sailed home to the States. As early as September 2, 1882, the Terre Haute Saturday Evening Mail reprinted a dramatic story from The Wasp, San Francisco’s acerbic satirical weekly perhaps best-known for its lurid political cartoons attacking Chinese immigration to the West Coast. (The Wasp has been called California’s version of Puck).

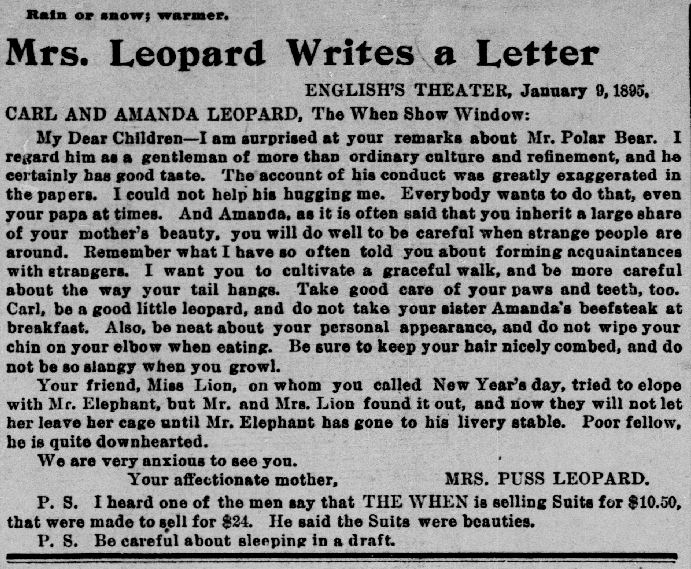

“An Unwelcome Present” was syndicated in other papers as far away as New Zealand and often got subtitled along the lines of “What the General’s Wife Thought of the Sultan’s Present.”

As far as I can tell, the tale first originated in the pages of The Wasp on August 5, 1882, where it ran under the title “That Present.” What I find especially fascinating is that the magazine’s editor from 1881 to 1885 was no less than the sardonic Hoosier cynic Ambrose Bierce, whose Devil’s Dictionary had its genesis as a column in the California weekly.

Like Wallace, Bierce fought at the terrifying Battle of Shiloh in 1862, serving as First Lieutenant in the ranks of the Ninth Indiana Infantry. During his days as a journalist, Bierce also worked for William Randolph Hearst at The San Francisco Examiner. To sell papers, the newspaper giant “routinely invented sensational stories, faked interviews, ran phony pictures and distorted real events.”

Did Bierce pen some “yellow journalism” about Lew Wallace and a Turkish harem girl? I wouldn’t put it past him. The Wasp’s editor was one of the biggest misogynists of his day and took constant swipes at women. To me, “An Unwelcome Present” sounds like one of Bierce’s tales or epigrams about the diabolical battle between the sexes, which he always portrayed as just slightly less gory than the bloodbath he and Wallace survived at Shiloh. In any case, the gossipy piece about his fellow Hoosier got published on Ambrose Bierce’s editorial watch.

Here’s the whole comic tale as it appeared on the front page of the Terre Haute Saturday Evening Mail:

Writer and poet Susan Wallace, who grew up in Crawfordsville and married Lew in 1852, had no reason to fear her husband would take up with a concubine. Yet Circassian beauties were all the rage during the long heyday of Orientalism.

The exotic Circassian mystique had been around for many decades. Inhabiting the Caucasus Mountains at the eastern end of the Black Sea near Sochi (the site of the 2014 Winter Olympics), Circassians were hailed by 19th-century anthropologists as the apogee of the human form. “Circassophilia” churned out many exotic myths about these people in Europe and America. During the Enlightenment, the French writer Voltaire popularized a belief that Circassian women were the most beautiful on earth, “a trait that he linked to their practice of inoculating babies with the smallpox virus.” In the 1790s, the invention of the so-called “Caucasian” race occurred when Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, one of the founders of physical anthropology, compared the anatomy of the beautiful, martial Circassians of what became North Turkey and southern Russia with the rest of humanity and categorized the mountain folk as the least “degenerate” humans.

Yet by the time of Wallace’s tenure in the Middle East in the 1880s, these tough mountaineers had been subdued by the Russians and Ottomans after long years of bloody warfare. Legends about dazzling Circassian beauties abounded even as Circassia itself disappeared from the map. One popular story went that the main source of wealth for fathers in the region was their breathtakingly beautiful daughters, whom they sold off to Turkish slave markets, though as writer in The Penny Magazine thought in 1838, Circassian women were “exceedingly anxious to be sold,” since life in a Turkish harem was “preferable to their own customs.” In Constantinople, they were highly prized in harems — not to be confused with Western prostitution. American abolitionist and women’s rights activist Lydia Maria Child devoted a chapter to Circassia in her 1838 History of the Condition of Women.

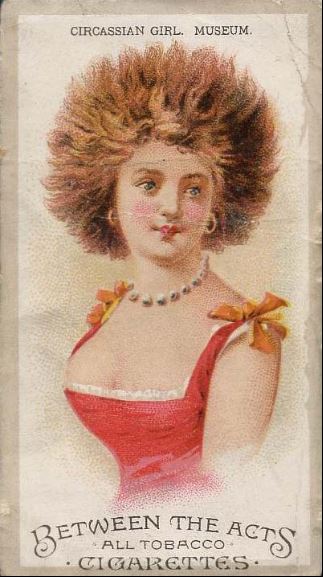

The horrible trade in female slaves from the Caucasus was alive and well in the mid-1800s, when an alleged glut in the market led to their devaluation. Good timing for American circus mogul P.T. Barnum. In May 1864, he wrote to one of his employees, John Greenwood, who had traveled to Ottoman Cyprus to try to buy a Circassian girl on Barnum’s behalf. Over a year after the Emancipation Proclamation in America, the circus owner wrote:

I still have faith in a beautiful Circassian girl if you can get one very beautiful. But if they ask $4000 each, probably one would be better than two, for $8000 in gold is worth about $14,500 in U.S. currency. So one of the most beautiful would do. . . But look out that in Paris they don’t try the law and set her free. It must be understood she is free. . . Yours Truly, P.T. Barnum

Barnum’s fascination with acquiring and exhibiting women in his shows took on the elements of a personal erotic and racial fantasy. Though most were “local girls,” as newspapers knew, Barnum billed his “Circassians” as escaped sex slaves and “the purest specimens of the white race.” Figments of Barnum’s imagination, these women joined the ranks of the dime-show freaks, part of the offbeat spectacle of bearded ladies, sword-swallowers, and snake-handlers that drew in paying crowds. Barnum’s harem girls enhanced their hair with beer to create a farfetched “Afro” look.

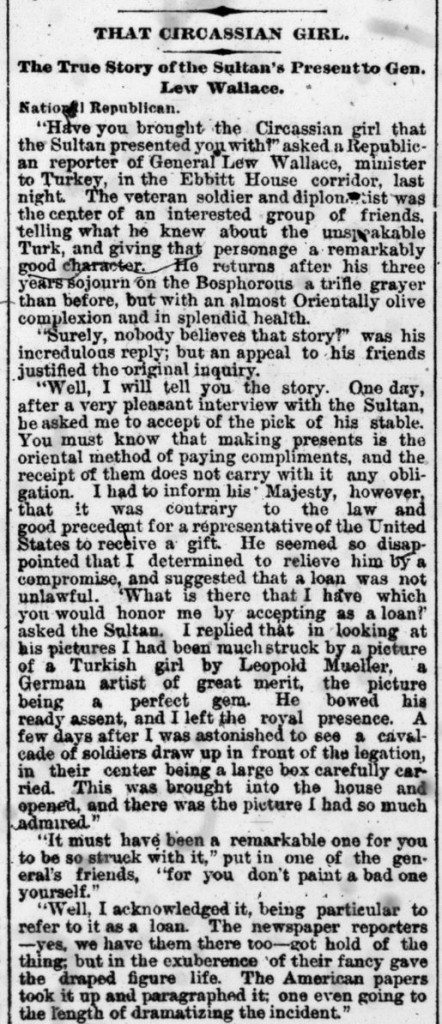

This was not the kind of Circassian girl alleged by a “yellow journalist” to have been bestowed to Lew Wallace in Turkey. On the eve of his return to America, the General tried to clear things up with the press. The Indianapolis Journal carried this twist in the story on June 30, 1884:

The website of the General Lew Wallace Study and Museum in Crawfordsville gives a slightly different perspective altogether:

The website of the General Lew Wallace Study and Museum in Crawfordsville gives a slightly different perspective altogether:

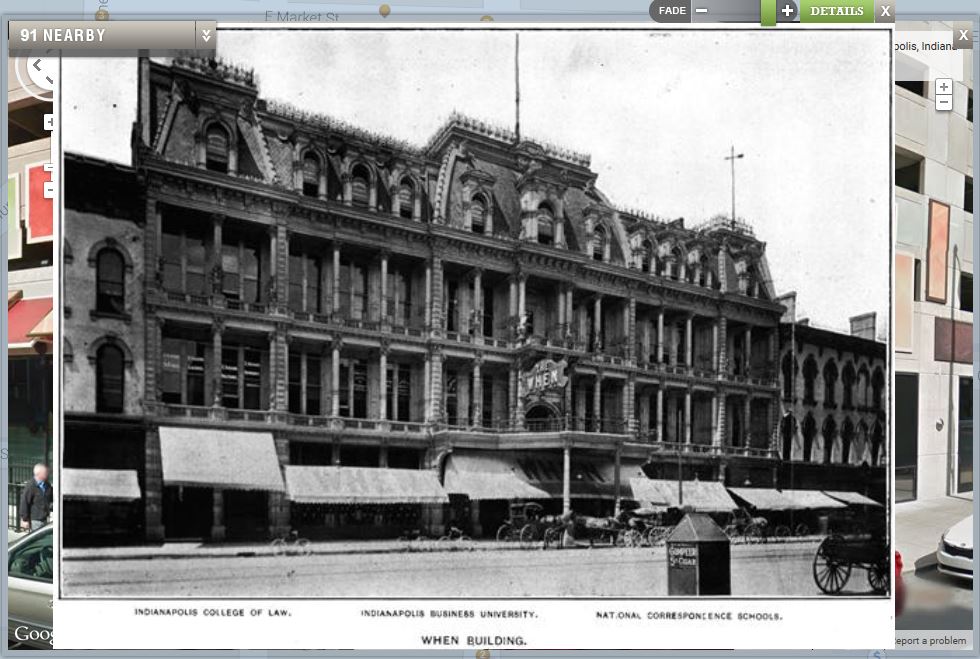

As his tour of duty as envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary to the Ottoman Empire came to an end in 1884, Lew Wallace was offered a number of gifts from his friend, Sultan Abdul Hamid II. These included Arabian horses, jewels, and works of art. As a representative of the government of the United States, Wallace graciously declined these expressions of friendship and gratitude. According to legend, as Wallace closed his office and packed his residence, the Sultan was able to secretly include the painting called The Turkish Princess, some elaborate carpets and a few other items in the shipping crates. The crates were delivered to Crawfordsville before Lew and Susan returned home. These items sent by the Sultan remained undiscovered by Wallace until he was back in Crawfordsville and opened the crates. The Turkish Princess, said to be one of the Sultan’s daughters, remains one of the highlights of the Study.

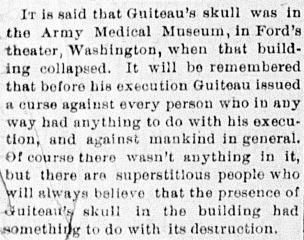

Wallace’s biographers Robert and Katharine Morsberger add a further note: “Malicious gossip-mongers claimed that the sultan had also provided Wallace a Circassian slave girl for his carnal pleasures and commiserated with Susan Wallace on her husband’s alleged concubine. Both the sultan and the American minister had too much honor and mutual respect for such an arrangement.”