With Christmas Eve approaching, you might have the tune “Chestnuts Roasting Over an Open Fire” playing somewhere. A hundred years ago, chestnuts were actually on the path to becoming a rarity, as a huge blight that was killing off chestnut trees began dramatically reducing their numbers. The blight got so bad that chestnut trees nearly became extinct in the U.S. Yet as World War I was still raging in Europe, American chemists found a clever new use for chestnuts — alongside coconut shells, peach stones, and other hard seeds. Disturbingly enough, this was for use in the gas mask industry.

During the last year of the “War to End All Wars,” the Gas Defense Division of the Chemical Warfare Service of the U.S. Army began issuing calls for Americans to save fruit seeds. As refuse from kitchens and dining room tables, these would typically have been classified as agricultural waste. Conscientious Americans began to put out barrels and other depositories for local collection of leftover seed pits. These came from peaches, apricots, cherries, prunes, plums, olives, and dates, not to mention brazil nuts, hickory nuts, walnuts, chestnuts, and butternuts. In the rarer instance that Americans had any spare coconut shells left over, these came in handy, too.

How on earth could seeds and shells contribute to the war against Kaiser Wilhelm’s Germany?

World War I was the first conflict to involve the use of toxic chemicals meant to incapacitate and kill soldiers. Soldiers were warned that death would come at the fourth breath or less. Fritz Haber, a German chemist who won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1918 for his research into the creation of synthetic fertilizers, also helped spearhead German use of ammonia and chlorine as poisonous weapons used in trench warfare. (Haber’s wife, also a chemist, committed suicide out of shame at her husband’s promotion of poison gas.) Haber additionally pioneered a gas mask that would protect German soldiers from their own weapons. Ironically, Frtiz Haber was Jewish. He later fled Germany in 1933 during the rise of Adolf Hitler, a few years before the poisons he experimented with were used by the Nazis to exterminate Jews and others during World War II.

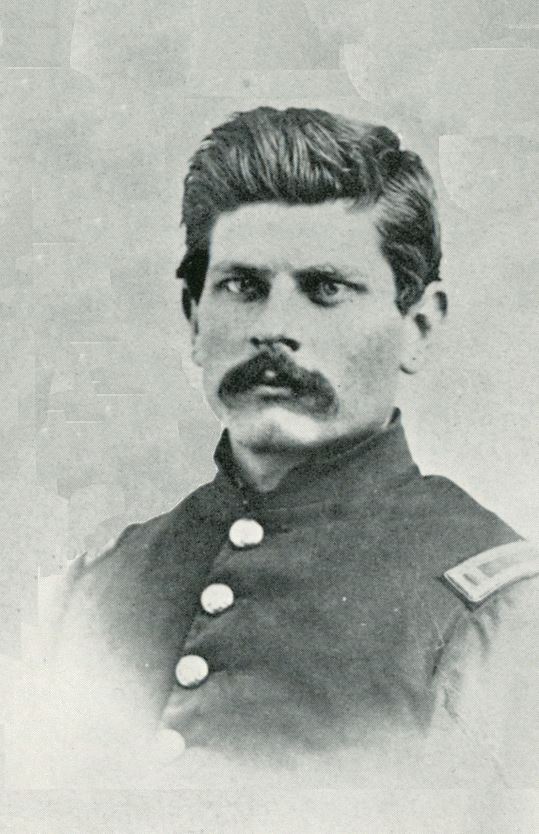

Haber, however, wasn’t the only chemist at work on a gas mask. One such device was invented by a mostly-forgotten American chemist from the Hoosier State, James Bert Garner.

Garner was born in Lebanon, Indiana, in 1870, and earned a Bachelor’s and Master’s in Science at Wabash College in Crawfordsville, where he studied under Scottish-American chemist Dr. Alexander Smith. (Like many doctors and scientists, Dr. Smith had done his own graduate studies in Munich, Germany, in the 1880s. He taught chemistry and mineralogy at Wabash for four years until moving to the University of Chicago and Columbia University.) Dr. Garner served as head of Wabash’s chemistry department from 1901 to 1914, the year World War I erupted. The Hoosier chemist then took a job at the Mellon Institute for Industrial Research at the University of Pittsburgh.

After reading an account of a toxic gas attack on French and Canadian soldiers during the Battle of Ypres in 1915, Garner began working on a more effective respiratory mask than was then available. Primitive versions of gas masks and protective apparatuses designed to ward off disease had been around for centuries, from 17th-century plague doctor’s outfits to a mask pioneered by the German scientist Alexander von Humboldt in 1799, when Humboldt worked as a mining inspector in Prussia. In the 1870s, Irish physicist John Tyndall also worked on a breathing device to help filter foul air, as did a little-known Indianapolis inventor, Willis C. Vajen, who patented a “Darth Vader”-like mask for firemen in 1893. (Vajen’s masks were manufactured in an upper floor of the old Indianapolis Public Library.)

While working at Pittsburgh’s Mellon Institute, Dr. Garner advanced a method for air filtration that he had first experimented with at Wabash College and the University of Chicago. Garner’s mask, co-designed by his wife Glenna, involved the use of a charcoal filter that absorbed sulphur dioxide and ammonia from the air stream. Garner’s World War I-era invention wouldn’t be his last attempt to reduce the deadly impact on the lungs of dangerous substances. In 1936, he patented a process to “denicotinize” tobacco.

Manufacturers of Garner’s masks found that coconut shells actually provided one of the most useful materials for filtering toxic poison. With a density greater than most woods, hard fruit seeds and nuts were also found useful in the creation of charcoal filters. All over the U.S., local Councils of Defense, citizens’ committees (sometimes highly intrusive) were set up to promote production of war materiel and monitor domestic waste. These committees encouraged Americans to hang onto seed pits for Army use.

“Cleaned, dried, and then subjected to high temperature,” reported Popular Science Monthly, “the stones become carbonized, and the coal, in granulated form, is used as an absorbent in the manufacture of gas-masks.” Charcoal rendered from fruit seeds, coconut shells, etc., was found to have a “much greater power of absorbing poisonous gases than ordinary charcoal from wood.”

How many seeds were needed? One source cites a government call for 100 million of them. In a letter from J.S. Boyd, First Lieutenant in the Chemical Warfare Service of the U.S. Army, which appeared in the Indianapolis News in September 1918, Boyd informed the public that “Two hundred peach stones, or seven pounds of nut shells, will make enough carbon for one mask. Think of that! And one mask may save a soldier’s life.” At this rate, a hundred million peach stones could produce 500,000 gas masks.

Tolstoy’s classic novel needed a new title: War & Peach.

The seed-collection campaign quickly took to American newspapers.

In Indianapolis, the Marion County Council of Defense urged local consumers and businesses not to waste products and labor during Christmas shopping. (The waste of certain human lives for political ends seemed to bother them less, and the Indiana council worked to censor all criticism of the war from pacifists and socialists.) At the committee’s urging, local restaurants, hotels, and stores, including L.S. Ayres and the William H. Block Co. — the largest department stores in Indianapolis — collected agricultural leftovers in bins out front. The Block Co. advertised its support for the peach stone campaign during a September call to “Buy Christmas gifts early.” Fortunately, the war was over by Christmas 1918.

Local Councils of Defense chided businesses and Christmas shoppers for wasting labor and even kept up some surveillance on them. Department stores were forbidden to hire extra help during the 1918 Christmas season, meaning no special workers could carry customers’ purchases back to their homes. The councils explicitly asked Hoosiers to carry their own packages and urged managers and employees to report any business that was hiring “extra help” for the holiday.

Emphasis on gathering peach stones in particular picked up momentum in September 1918, since that month marked the beginning of harvest time. As for wild nuts, children all over the U.S., including the Boy Scouts, scoured American forests for walnuts, hickories, and butternuts. One photo in Popular Science Monthly showed a “gang bombarding a horse-chestnut tree” and stated that they were “enlisted in war work.” Children brought nuts and seed pits to 160 army collection centers.

A call for peach stones in the film magazine Moving Picture World encouraged movie theater owners to offer special matinées to support seed-gathering. The magazine suggested keeping admission at the regular price, but with the donation of one peach stone required for entry. Once inside, moviegoers were likely to see a slideshow from the Army’s Gas Defense Service as a “preview.” One theater owner in Long Island was especially generous to children. Children, however, apparently took unfair advantage of him:

The call for seed pits should have come earlier. Ninety-thousand soldiers died from toxic gas exposure in the First World War, with over a million more suffering debilitating health problems that often lasted for the rest of their lives. Almost two-thirds of the fatalities were Russian. And chemical warfare had just begun.

Though propaganda pinned the barbaric use of chemicals squarely on the Kaiser’s armies, the British used toxins during and after the war. Under Winston Churchill — War Secretary in 1920 — the RAF dropped mustard gas during its attempt to put down Bolshevism in Russia, the same year that Churchill is alleged to have authorized the use of deadly gas in fighting an Iraqi revolt against British rule in the Middle East. One English entomologist, Harold Maxwell-Lefroy, was allegedly curious about the use of bugs in “the next war” to spread disease behind enemy lines.

During World War II, the U.S. briefly experimented with the creation of biological weapons. At the Vigo Ordinance Plant, an ammunition facility in Terre Haute, the Army looked into the production of deadly anthrax in 1944 as part of the little-known U.S. biological weapons program. According to some sources, those chemicals were meant to have been used in proposed British anthrax bombs, which would have killed entire German cities. Fortunately, the end of the war came before any significant amount of the material was ever produced. The Vigo County plant was later acquired by Pfizer.

As for native Hoosier chemist James Bert Garner, he kept on inventing, attempting to save lives in spite of the brutality of war. Garner lived with his family in Pittsburgh, where he worked as director of research for the Pittsburgh-Des Moines Steel Company — the company that built the Gateway Arch in St. Louis starting in 1963.

Garner, however, died in 1960 at age 90. Sometimes cited as the inventor of the gas mask — though he was really just one of many — he is buried at Pittsburgh’s Homewood Cemetery.

In spite of his efforts, chemical warfare has gone on to kill millions.

Contact: staylor336 [AT] gmail.com