Only one in four Women’s History Months occurs in a Leap Year — or if you want to use the fancy name given by professional time-keepers and astronomers, you can call it an “intercalary” or “bissextile” year.

Hollywood has churned out a few bad movies about what was probably an old Celtic custom at first, whereby women could take the initiative in proposing to a man. But American newspapers were having fun with this folk tradition well over a century ago. And some women did take the opportunity.

Leap years have been around since Roman times, when Julius Caesar simplified the messy Roman calendar. Since the earth doesn’t take a precise number of 24-hour days to go around the sun, fractions of days accrue. Before Caesar’s time, Roman astronomers just added an entire 22-day-long month to their 355-day calendar every two years. Caesar’s astronomers opted for 365 1/4 days, with the quarter-day adding up to a full day every four years. Yet even that extra quarter day isn’t exactly six hours long, a problem that led Pope Gregory XIII in 1582 to fine-tune Caesar’s calendar. More confusing still: in the Gregorian system, not even every fourth year is a leap year. In folk tradition, that accounts for the occasional year when women who want to pop the question have to be especially diligent — or else wait another eight. At least if they care about tradition.

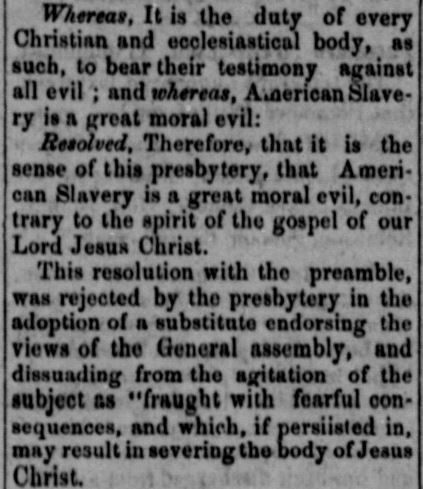

(Indiana American, Brookville, April 29, 1836.)

The origin of the “ladies’ privilege” goes back a long time, though no one knows how long for sure. A popular but doubtful origin myth hinges around a medieval Irish saint, St. Brigid of Kildare — who might never even have existed.

If she was a real woman, Brigid would have been born in the middle of the 5th century, allegedly to an enslaved Christian mother and a pagan Irish chieftain, who sold her mother to a Druid — a Celtic priest and shaman. The life of St. Brigid might be one big folk legend, however, since she shares a name and many attributes with an old Irish fertility goddess. Irish folklorist Lady Augusta Gregory wrote in 1904 that the goddess Brigid was “a woman of poetry, and poets worshiped her, for her sway was very great and very noble. And she was a woman of healing along with that, and a woman of smith’s work, and it was she first made the whistle for calling one to another through the night.” The same could be said for Saint Brigid.

Whether St. Brigid was real or not, many stories about her are clearly imaginary. But folklore and poetry have a truth all their own. Several tales tell of how the saint protected women and gave marriage advice to men — often while guarding her own virginity and independence amid the violence of the remote, rugged Emerald Isle. When Brigid dedicated herself to the service of God and others as a nun, her greedy brothers, one story goes, hated her for denying them the “bride price” they would have been entitled to. As a crowd taunted Brigid for not marrying, one Irishman shouted: “The beautiful eye which is in your head will be betrothed to a man — though you like it or not.” Brigid’s reply was shocking: she jabbed a finger into her eye and blinded herself, then cried out, with blood spurting everywhere: “Here is that beautiful eye for you. I deem it unlikely that anyone will ask you for a blind girl.” Miraculously, Brigid’s vision healed. As for the man who taunted the saint, both his eyeballs burst in his head.

In legend, at least, Brigid was probably the most powerful woman in Ireland. Even in the afterlife, she supposedly still watches over midwives, illegitimate children, abused women, sailors, poets, chicken farmers, scholars and the poor. But what about Brigid and Leap Year?

Out of concern for women — and probably for children born out of wedlock — the angry saint fumed about men dragging their feet when it came to proposing marriage and committing to a partner. (Nineteenth-century feminists would later oppose the liberalization of American divorce laws for reasons not unlike what spurred St. Brigid to action over a thousand years earlier: slipping out of marriage was a way for lecherous and abusive men to escape their duties.) Brigid, according to legend, asked St. Patrick to make an exception to custom and allow women to “pop the question” every leap year. The new custom still seems sexist to some, perhaps, but the Irish tale is almost definitely fable as far as Brigid goes: if she ever lived, she would have been about ten years old when St. Patrick died.

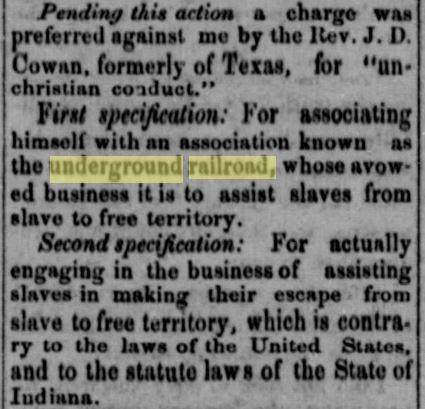

Variants on the tale show up in Scottish folklore and English common law. According to an English book from 1606, Courtship, Love and Matrimonie, any Englishman who refused “the offers of a laydie” on leap year could be fined and even denied “the benefits of the clergy.” Two-hundred years later, the Indiana American quoted that passage:

(Indiana American, Brookville, March 1, 1844.)

“Common” law or not, the custom was rare in America even as newspapers began to pick up on it in the mid-1800s. Rising Irish immigration might have been a factor in the sudden interest in the custom, but newspapers themselves could have been the ones spreading the “folk” idea. (After all, Sadie Hawkins Day, a “pseudo-folk tradition” where girls ask boys out to a dance, originated with Al Capp’s popular hillbilly comic strip Li’l Abner in the 1930s. Sadie Hawkins Day, however, comes every year, usually November 15, the date she first appeared in a cartoon in 1937.)

(A Sadie Hawkins dance in Virginia, 1950s.)

By the 1840s, the American press was mentioning leap year marriage proposals — and anything else like them that seemed out-of-the-ordinary. A clip from the Evansville Daily Journal, published just before the Mexican War, reported a similar tradition in Panama, a story that might have been brought back by American sailors.

(Evansville Daily Journal, April 24, 1845.)

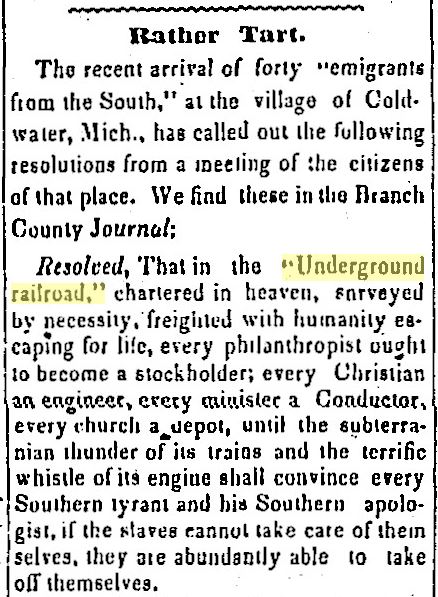

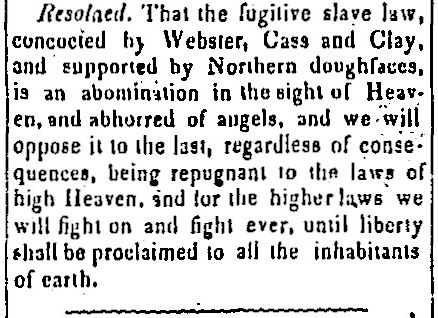

In the leap year 1848 — a year of tumultuous revolutions in politics and love — the Brookville Indiana American reprinted this clip from a Hoosier wag in Richmond, Indiana, who obviously enjoyed the idea of women proposing to men. They had fifteen days left, since the tradition didn’t require women to propose on February 29. Any time before midnight on New Years’ Eve was good enough.

(Indiana American, Brookville, December 15, 1848.)

Also in 1848, the Indianapolis Locomotive, an “entertainment” paper written in the vein of Charles Dickens’ Pickwick Papers (a bestseller at the time) and filled with more wit and poetry than news, published a strange story about sexual role-reversal. A lot of tales like this were taken out of Eastern newspapers that came off steamboats or trains. “A Story of Leap Year,” by Joe Miller, Jr., probably first appeared in the St. Louis Reveille. The story, which satirizes conventional courtship and sentimental wooing, is funny, if also a bit sexist. The bold Susan comes over to ask the bashful Sam for his hand in holy matrimony:

(The Locomotive, March 11, 1848.)

Every year, a few women really did ask men to tie the knot, though most couples were already “courting” to begin with. Yet every four years, illustrators, cartoonists, and postcard makers played around with a major source of male fear and trembling, anxiety and dread: a proposal coming from an unwanted woman “out of the blue.”

In popular culture and superstition, any man who turned down a woman — even a total stranger — ran the risk of being cursed or at least having to stumble through an awkward, hopefully gentleman-like, rejection. (No “spite and contumely,” as the 17th-century English book put it.) A lot of drawings and postcards played on economic, class, age, and physical differences, though not all did:

Many women today consider the Leap Year tradition degrading and insulting, and they may be right. But as the women’s rights movement gathered steam in the 1800s, not every woman thought the overall gist of the tradition was bad. One was the famous suffragette and news correspondent Inez Milholland.

Born in 1886, Milholland came from a wealthy family in Brooklyn and graduated from prestigious Vassar College, a women’s college in Poughkeepsie, New York, in 1909. She became a radical and socialist at Vassar, educating fellow students about socialist principles — which brought her into conflict with the school’s leadership. Milholland also served as captain of the hockey team at Vassar. She was denied admission to Yale, Harvard and Cambridge law schools because of her gender, but earned a law degree at NYU in 1912.

As a trained lawyer and activist, Milholland was especially interested in prison reform, ending child labor and prostitution, and achieving equality for women and African Americans. In her late twenties, she helped investigate conditions at New York’s Sing Sing prison, handled divorce and criminal cases, and supported female factory workers on strike in New York and Philadelphia. While reporting from the frontlines in Italy during World War I, the Socialist news correspondent wrote anti-war articles and was expelled by the Italian government, at war with Germany and Austria.

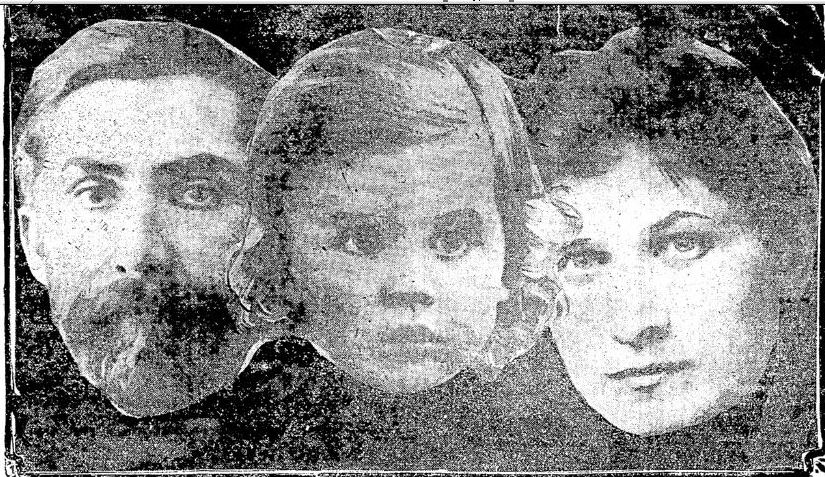

(Inez Milholland.)

As a supporter of “free speech in love,” honesty, dignity, and open communication between the sexes, Inez Milholland made a famous marriage proposal — though it didn’t happen during a leap year. She stressed that a woman should be free to ask a man to marry her on any day of any year, not just every fourth year. Milholland lived up to her principles.

In 1913, while on a cruise in Europe, the woman’s rights activist proposed to Eugen Jan Boissevain, a Dutch coffee importer who came from one of the wealthiest families in Amsterdam. (Boissevain’s uncle, however, was, like Milholland, a Socialist who gave up his fortune and moved to Alberta to be a farmer and labor organizer.) The two had known each other for just a month but got married within days. He moved to New York with her.

Sadly, their marriage was short. At age 30, Inez Milholland died of anemia in Los Angeles in 1916 while campaigning for the National Woman’s Party. Seven years later, Eugen Boissevain married the great American poet Edna St. Vincent Millay. He died in Boston in 1949.

The Day Book of Chicago told some of the unusual story, published the year of her death — a leap year:

(The Day Book, Chicago, January 3, 1916, Noon Edition.)

Milholland’s husband agreed, and had this to add:

(The Day Book, Chicago, January 3, 1916, Noon Edition.)

Contact: staylor336 [AT] gmail.com