A few weeks ago, we ran a post on how peach stones, chestnuts, and coconut shells got enlisted into World War I. In 1917, the U.S. government began a campaign to gather fruit pits and other agricultural waste that could be used in manufacturing charcoal filters for army gas masks — a life-saving device partly invented by Hoosier chemical engineer James Bert Garner.

The “war to end all wars,” of course, failed to do so. Twenty years later, America was on the verge of an even worse conflict. And in 1942, the familiar specter of junk rallies and war-bond drives returned to American newspapers.

Across the U.S., papers advertised the army and navy’s dire need for rubber, scrap iron, and “anything made of metal.” Most of the ads were nationally syndicated, and no one local newspaper can take credit for these darkly comic illustrations of ordinary domestic items turned into deadly weapons.

Like a scene from Walt Disney’s Beauty and the Beast, old radiators, lawn-mowers and worn-out tires were turned into instruments of fighting and killing, from rifles and shells to grim-looking gas masks and hand grenades.

The government’s scrap conservation campaign broke down the math. This ad comes from Dale in Spencer County, Indiana, just down the road from Lincoln’s boyhood home and the small town of Santa Claus.

Drawn by an illustrator for the Conservation Division of the War Production Board, the illustrations were taken out and paid for by the American Industries Salvage Committee. Business at local scrap yards was booming in 1942. The ads stated that scrap material would be purchased at government-controlled prices.

In what was actually one of America’s first recycling programs, the call went out for refrigerators, garbage pails, broken garden tools, lengths of pipe, burlap bags, manila bags, copper wires, zinc, lead, tin, and any kind of old rubber. Rusty scrap metal, the committee reminded Americans, was “actually refined steel, with most impurities removed — and can be quickly melted with new metal in the form of pig iron to produce highest quality steel for our war machines.” In 1942, the U.S. armed forces — just months after Pearl Harbor — needed an additional six million tons of scrap steel for weapons production.

The government also encouraged “good Americans” to give up something else: Sunday country drives and “joy-riding.” Unnecessary shopping trips to town and failure to use public transportation sapped gasoline at a time when Nazi submarines were torpedoing hundreds of oil tankers off the Atlantic Coast. Unnecessary driving and fast driving also added to the rubber shortage by wearing down tires. So did driving with the wrong tire pressure, as a Phillips 66 ad informed the patriotic public.

If only that conservation effort could have carried over into peace time. . . no matter how restless the joy-riding doggies got:

Since farmers were likely to have plenty of scrap metal hanging around their property, the salvage committee’s ads tended to target rural areas and small towns. Dale, Indiana, was one, but the illustrations appeared nationwide.

Beneath the dark humor of seeing a Japanese soldier knocked on the head with grandma’s laundry iron or her kitchen teapot, some of these cartoons were fairly racist. Though cartoonists are usually allowed to take liberties to provoke discussion, artists at all times –especially in war time — have sometimes helped destroy innocent lives.

The hysteria that targeted German Americans during World War I — when Indiana and many other states went so far as to criminalize teaching German to children — rarely occurred during World War II, though about 11,000 German nationals were detained. The same can’t be said of the fate of Japanese Americans, over 100,000 of whom were herded up and imprisoned in detention camps out West.

Yet as always, some Americans rose above hysteria and fear. In 1942, Quaker-led Earlham College in Richmond, Indiana, became one of the few U.S. schools to allow Japanese Americans to continue their education during the war. The decision of Earlham’s President William Cullen Dennis, who cooperated with the Japanese American Student Relocation Council to admit six students from the newly-militarized West Coast, was controversial.

(Kokomo Tribune, September 30, 1942.)

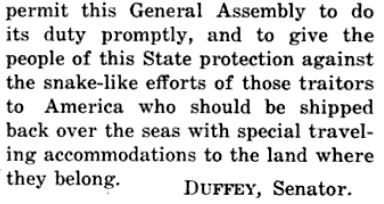

In September 1942, the local branch of the Junior Order of American Mechanics, a youth group, sent Earlham’s president a resolution protesting the students’ presence on campus. The OAM was originally an anti-Catholic and nativist fraternal group organized in Philadelphia in 1844 to resist the hiring of “cheap foreign labor” (i.e., Irish). Richmond’s Junior OAM captured a lot of local sentiment and tried to encourage other “patriotic and fraternal orders” in town to follow suit. Richmond Mayor John Britten was forced to advise the FBI of the “hostile attitude of the community toward the students.”

(Rushville Republican, September 30, 1942.)

Dennis stood by his decision, citing that the move was in accordance with the school’s Quaker religious principles and “the ideals for which we are fighting.” Yet he refused to denounce the Federal government’s original decision to move them off the West Coast. The Japanese pupils — along with about 1,900 others now scattered across the Midwest and East — were kept under FBI surveillance.

Earlham wasn’t alone. A total of eight Indiana schools, all but one of them religious, admitted displaced Japanese Americans. These were DePauw, Valparaiso, Hanover, Franklin, Manchester, St. Mary’s (Notre Dame), Indiana Technical College, and Earlham. The Indianapolis-based Disciples of Christ also led a campaign critical of the West Coast interment camps and issued a resolution condemning the incarceration of 100,000 Americans without fair trial, calling it a mockery of American principles. That church was active in helping resettled families find jobs and housing across the Midwest.

(Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt, head of the Western Defense Command in San Francisco, issued orders forbidding Japanese American students at Oregon State University from using the library after 8:00 p.m. Corvallis Gazette-Times, April 3, 1942.)

(Corvallis Gazette-Times, April 2, 1942.)

Edward T. Uyesugi was one of the students who came to Earlham in 1942. Born in 1922 and raised in Portland, Oregon, he was one of the ten students forced to leave Willamette University in Salem after the Federal “evacuation” of April 1942. In Richmond, Uyesugi studied biology. He also met Paoli native Ruth Farlow, who was studying Latin, English and journalism. Ruth, a Quaker, wrote for the Richmond Palladium (currently being digitized by Hoosier State Chronicles.) The couple went on to get married in Washington State in 1946.

Farlow had gotten her first teaching job in Oregon, but was fired after one semester for her marriage to a Japanese American. (“Interracial marriage” was frowned on in every state and was still illegal in many.) The Uyesugis eventually came back to Indiana, raising three children in Ruth’s native Orange County, where he worked as an eye doctor and she taught journalism at Paoli High School. In 1999, Ruth Uyesugi was inducted into the Indiana Journalism Hall of Fame. She’s also the author of a 1977 autobiographical novel, Don’t Cry, Chiisai, Don’t Cry, a war-time love story set in Indiana and Oregon.

(Ruth Farlow, seated center, and Edward Uyesugi, right, both served on the editorial staff of the Earlham Post in 1944. Uyesugi wrote a sports column and also played on the football team.)

In 1942, Hoosier readers may have had their first encounter with a rising star in the world of illustration — Theodor Seuss Geisel, a third-generation German American originally from Springfield, Massachusetts. Geisel studied at Dartmouth and Oxford before joining the staff of the humor magazine Judge in New York City in the 1920s. His first published cartoon came out in the Saturday Evening Post in July 1927. Surviving the lean times of the Great Depression by drawing ads and logos for companies like General Electric, Standard Oil, and the Narragansett Brewing Company, Geisel got his first major national exposure during a Standard Oil campaign to market motor boat lubricants.

Nearly expelled from Dartmouth as an undergrad for drinking gin during Prohibition, the quirky illustrator had been banned from publishing cartoons in the college’s writing magazine. He got around it by signing himself “Dr. Seuss,” his middle name. (The name is actually pronounced “Soiss,” but the illustrator gave in to the American pronunciation.)

By 1942, Dr. Seuss — a fervent, scathing opponent of isolationists and pacifists who wanted to keep America out of World War II — was busy trying to lubricate public opinion instead of motor boats. Though frequently mistaken as a Jew because of his name and his appearance, Dr. Seuss was a German Lutheran.

(An anti-isolationist cartoon published in 1941, before America went to war against Germany, Italy and Japan.)

In the wake of American entry into the war — and before he was ever at work on The Grinch and The Cat in the Hat — Dr. Seuss drew cartoons for the U.S. Treasury Department as part of a war-bond drive. Roundly criticized since the 1940s, his caricatures of Japanese with buck teeth, pig noses and insect bodies came out in many American newspapers, including the tiny Dale News. Though Dr. Seuss deserves credit for apologizing for these cartoons after the war, the dehumanization of Asians may have influenced the U.S. decision to drop nuclear bombs on Japan in 1945, an event that was less likely to befall a Western European nation.

While “Dr. Seuss” also depicted Hitler with a pig snout and animal body, Geisel’s 1942 cartoon of Japanese Americans receiving TNT and awaiting orders from Japan put him squarely in the tradition of fearing immigrants as “enemy aliens” — the long list of newcomers accused of undermining American safety and values. In the century before World War II, American periodicals were full of this material, some of it drawn by reformers like German American immigrant Thomas Nast. Only the characters changed — from Catholics, Jews, and Chinese to Germans, Japanese and Muslims.

(“Waiting for the Signal from Home,” Dr. Seuss, 1942.)

The “Tokio Kid” series, commissioned by the Douglass Aircraft Company and subsidized by the War Commissions Board, joined in on the recycling campaign. Posters showing the Japanese Emperor thrilled by Americans’ waste of items like scrap metal were little different from equally demonic depictions of the German Kaiser during World War I, but both episodes played off ethnic and racial prejudice. (Reform politics and bogus science were as guilty as everyday racism here. During World War I, “progressive” advocates of Prohibition had made identical charges against German American beer-lovers — for unpatriotically wasting grain. Dr. Seuss’ own father, brew master at the family-owned Highland Brewery in Springfield, Massachusetts, was driven out of his job when Prohibition shut the place down in 1919.)

As for social reform, that would have to wait for peacetime. It’s not clear who exactly cartoonist Nate Collier was satirizing when this illustration came out in the Dale News in February 1942, three months after Pearl Harbor. But we think we can guess.

Contact: staylor336 [AT] gmail.com