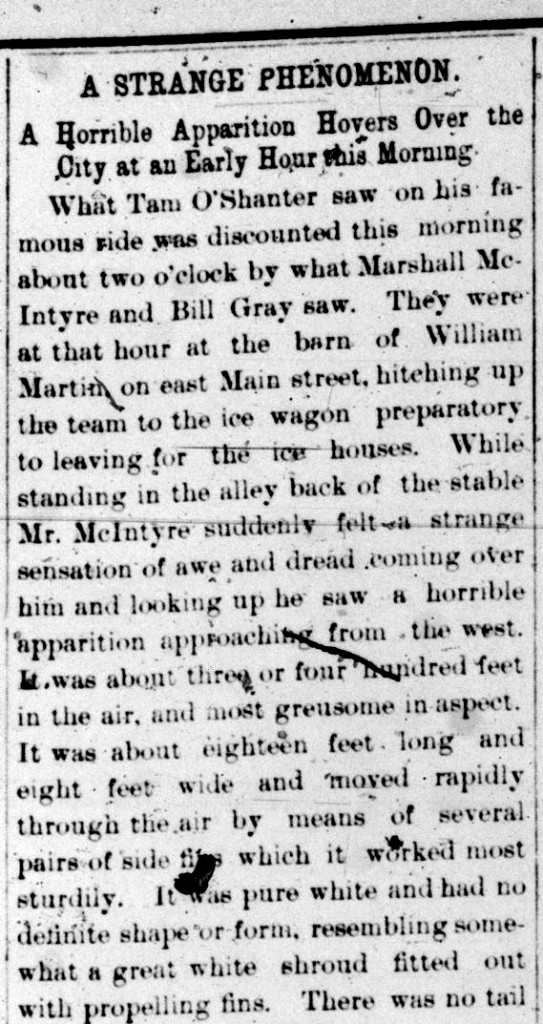

Around two o’clock on the morning of Saturday, September 5, 1891, Crawfordsville ice delivery men Marshall McIntyre and Bill Gray prepared their wagon for morning rounds when suddenly a feeling of “awe and dread” overcame them. Peering heavenward, the men saw a “horrible apparition.” The Crawfordsville Journal described what they witnessed:

[It was] about eighteen feet long and eight feet wide and moved rapidly through the air by means of several pairs of side fins. . . . It was pure white and had no definite shape or form, resembling somewhat a great white shroud fitted with propelling fins. There was no tail or head visible but there was one great flaming eye, and a sort of a wheezing plaintive sound was emitted from a mouth which was invisible. It flapped like a flag in the winds as it came on and frequently gave a great squirm as though suffering unutterable agony.

McIntyre and Gray observed the phenomenon hover three or four hundred feet in the air for nearly an hour before they retreated to the safety of the barn. They then quickly finished harnessing their horses and left the vicinity.

(Crawfordsville Daily Journal, September 5, 1891.)

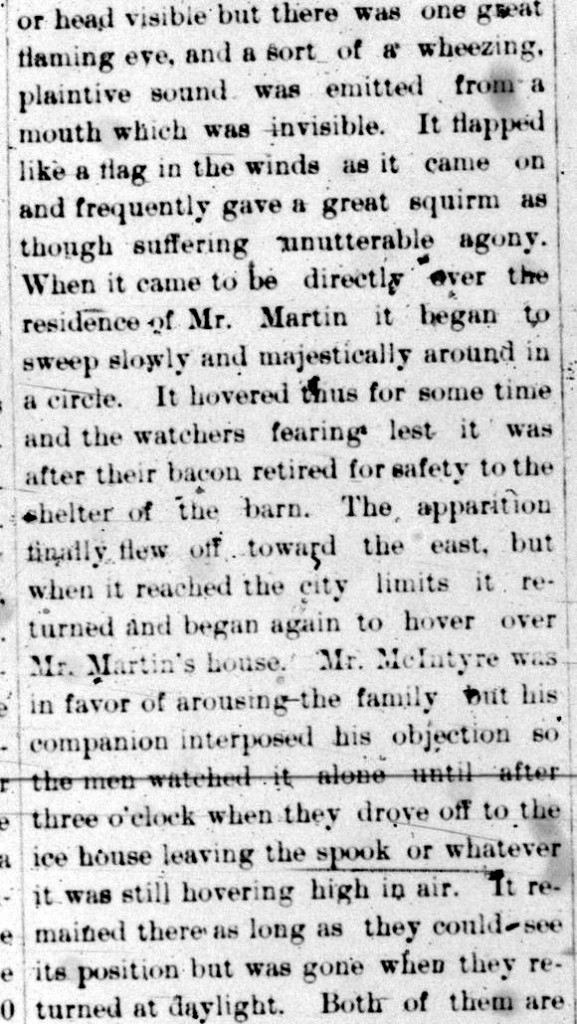

(Crawfordsville Daily Journal, September 5, 1891.)

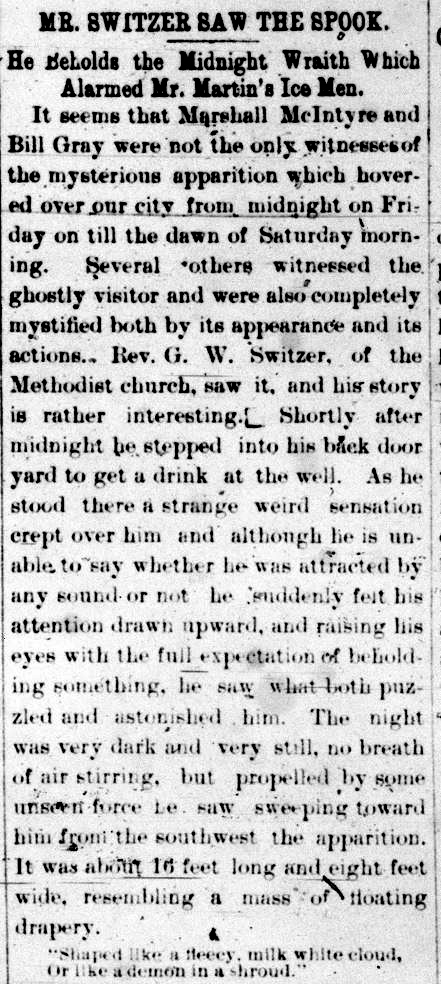

McIntyre and Gray weren’t the only witnesses that night. Perhaps the most reputable witness was G.W. Switzer, pastor of the First Methodist Church. Shortly after midnight, Rev. Switzer stepped out of his door to retrieve some water from the well when he espied the apparition. He woke his wife and they gawked as the thing “swam through the air in a writhing, twisting manner similar to the glide of some serpents.” As the Switzers watched, the mystery apparition seemed at one point as though it might descend on the lawn of Lane Place — home of late U.S. Senator Henry S. Lane’s widow — before it re-ascended and continued its circuitous route above the city.

(Crawfordsville Daily Journal, September 7, 1891.)

(Crawfordsville Daily Journal, September 7, 1891.)

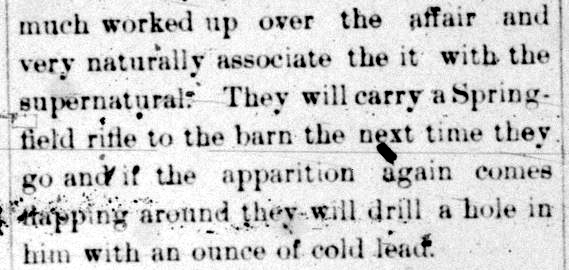

When Crawfordsville residents heard of the sighting, ridicule came quickly to the eyewitnesses. On the heels of Professor Burton, “Keeley’s Institute for inebriates” in Plainfield reportedly wrote to Rev. Switzer and invited him to visit — obviously to seek a cure.

(Crawfordsville Daily Journal, September 9, 1891.)

However, reports of the sightings also generated a number of believers. The Indianapolis Journal picked up the story, as did other newspapers across the country, including the Brooklyn Eagle. Mail regarding the sighting deluged the Crawfordsville postmaster. Some correspondents thought the sighting indicated that Judgment Day was near. A St. Louis woman, fearful of the spook’s western migration, wrote and asked if the apparition could be seen in the daytime, what color was it, and if the apparition had previously been in Ohio?

(Crawfordsville Daily Journal, September 11, 1891.)

(Crawfordsville Daily Journal, September 11, 1891.)

So what exactly did people see in the Crawfordsville sky that early September morning in 1891? Was it an apparition? UFO? A “rod,” like a 2008 episode of the History Channel’s Monster Quest implied? Or was it, as many internet sites suggest, an atmospheric beast!?!?

Fortunately, two eyewitnesses tracked the creature. John Hornbeck and Abe Hernley “followed the wraith about town and finally discovered it to be a flock of many hundred killdeer.” The many birds’ wings, white under-feathers, and plaintive cries contributed to the belief of many eyewitnesses that the creature(s) originated from the otherworld. Low visibility due to damp air likely compounded the misidentification. The Crawfordsville Journal hypothesized that the town’s newly installed electric lights caused the birds to become disoriented, hovering and wreathing their way above the city.

(Crawfordsville Daily Journal, September 8, 1891.)

(Killdeer Plover, watercolor by John James Audubon.)

(Killdeer Plover, watercolor by John James Audubon.)

If that explanation does not satisfy, there is an alternative one. During the prior week, newspapers circulated another story from Crawfordsville. This one was about a “balloon parachute craze” taking hold among the town’s boys. While that could explain the billowing, sheet-like apparition, it fails to account for the “wheezing plaintive sound” emitting from the aerial monster. Well, the same report about the parachute craze also mentioned that the boys also liked to send cats up in their balloons. Could this have been what McIntyre, Gray, and the Switzers saw and heard instead?

(Wichita Daily Eagle, Wichita, Kansas, September 4, 1891.)

As anti-climactic as these conclusions will be to modern readers — they’re also, no doubt, disappointing to cryptozoologists and ufologists — it is the complete story of the Crawfordsville monster as the Crawfordsville Journal reported it in early September 1891.

Incidentally, Crawfordsville published three newspapers in addition to the Journal. These were the Review, the Argus, and the Star. None of those papers so much as hinted that anything happened that September morning. This leads one to conclude that while a few citizens likely did see something unusual in the nocturnal sky, the Crawfordsville Journal overstated the incident to make an extra buck. And the nineteenth century was no more “gullible” than our own age. In other places around the world — like Fernvale, Australia, in 1927, and of course Roswell, New Mexico, since 1947 — reports of weird avian or other airborne visitors would pour in during the 20th century.

The Journal’s century old marketing ploy continues to generate lively discussion in the dark recesses of cyberspace and on late night radio talk-shows, where the Crawfordsville monster occasionally still goes out flying through the sky.