This month, the Indiana Historical Bureau is focusing on the history and culture of Allen County, Indiana. Here at Chronicles, we thought it would be an apt time to share some of Allen County’s newspaper history.

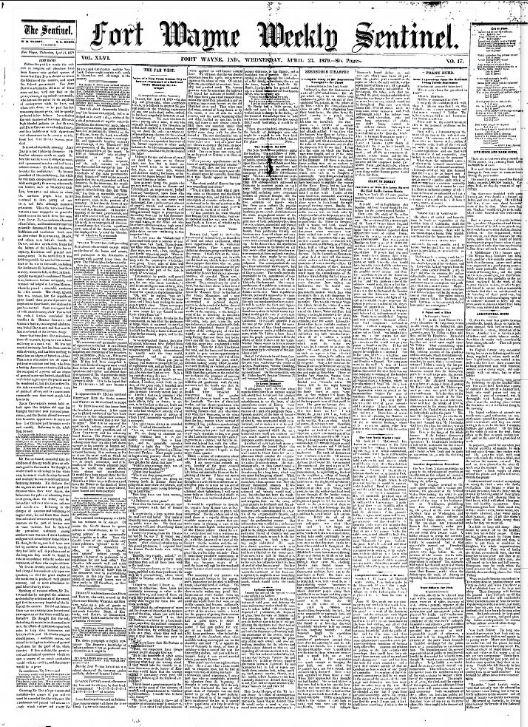

Fort Wayne, Allen County’s central city and the second-largest city in Indiana, produced most of the county’s newspapers. Thomas Tigar and Samuel V. B. Noel founded the Fort Wayne Sentinel, publishing its first issue on July 6, 1833. The Sentinel’s two publishers came from completely opposite political backgrounds. Tigar’s views aligned with the Democratic Party while Noel identified as a Whig. So, in an effort to avoid political conflicts, the paper initially started as an independent publication. Over the decades, the Sentinel changed hands and political affiliations routinely. For example, when Noel sold his stake to Tigar, it became a Democratic paper; when Gordon W. Wood owned it in the late 1830s, it switched to a Whig perspective. After decades of mergers, name changes (it was called the Times-Sentinel for a while), and multiple owners, the Sentinel merged with the daily News in 1918 and became the Fort Wayne News-Sentinel, the name it is still published under today.

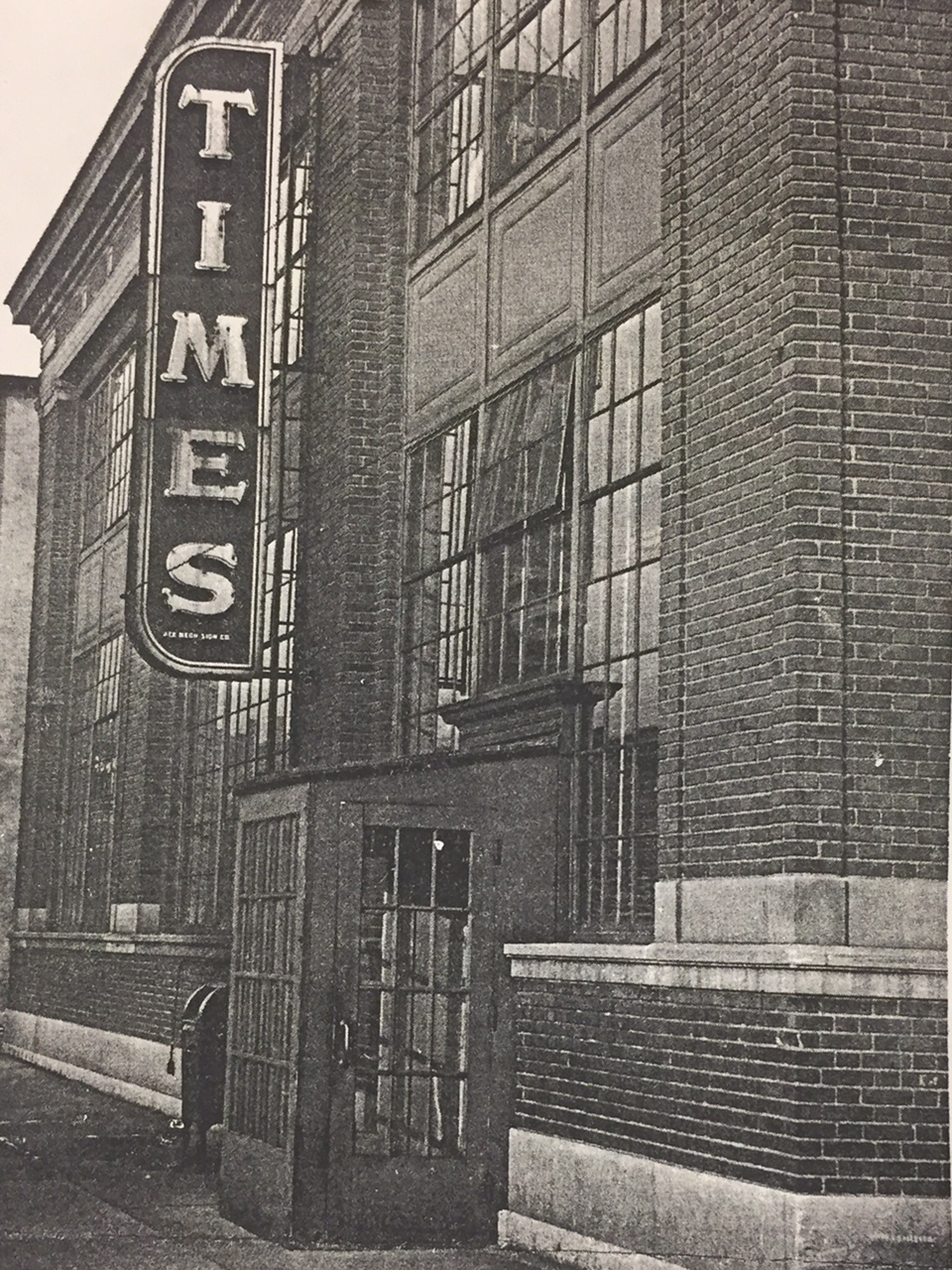

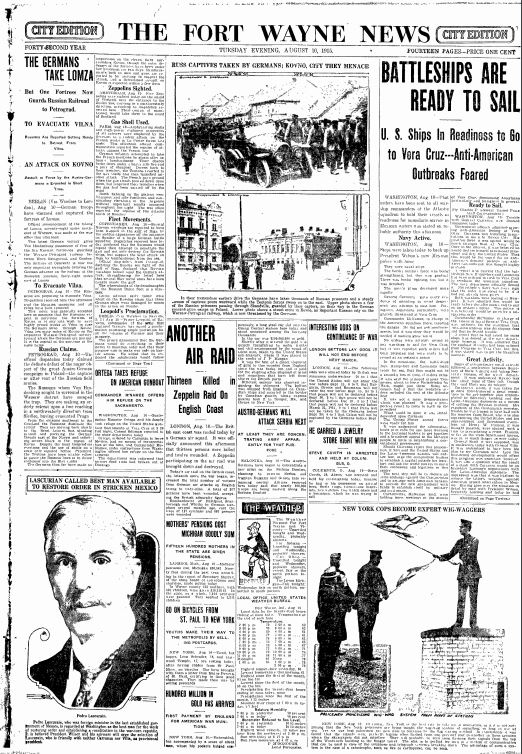

As for the News, William P. Page and Charles E. Taylor founded the Republican-leaning daily in 1874. Page made a 28-year career at the News, overseeing the development of weekly and daily editions. In 1902, he sold the paper to a partnership of entrepreneurs incorporated under the aegis of the News Publishing Company. This ownership maintained the paper until 1918, when it merged with the aforementioned Sentinel. Other notable Fort Wayne papers include the dailies Gazette (1863–1899), Journal (1881–1899), and Times (1855–1865).

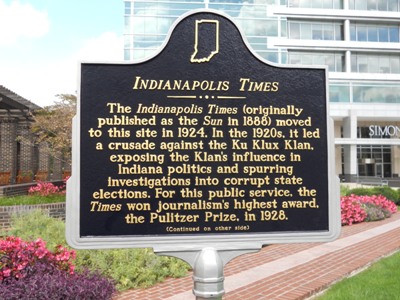

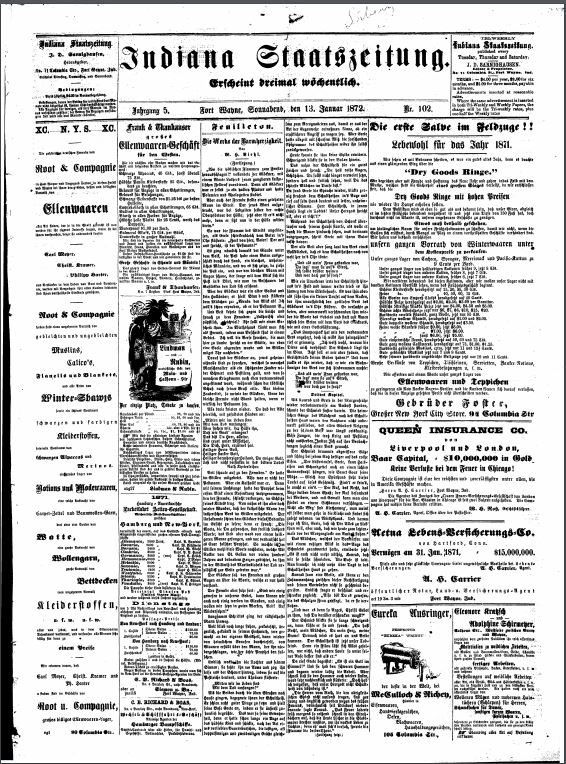

Fort Wayne’s prominent German immigrant population created a market for a slew of German language newspapers. One of the first was Der Deutsche Beobachter von Indiana, starting in 1843. Owned by Thomas Tigar (founder of the Sentinel) and edited by Dr. Charles “Carl” Schmitz, it published out of the offices of the Sentinel for a short time before it folded. The Demokrat, founded in 1876 by editor Dr. U Herrmann (possibly Dr. Alexander Herrmann, a physician in Fort Wayne during the time; “U Hermann” may have been a misprint.) and publisher Fred Schad, ran as a daily paper out of offices at 86 Calhoun for a few years. Catholic Germans were served by the weekly Weltbürger starting in 1883 until 1887. The Freie Presse-Staats-Zeitung, founded in 1908 with the merger of the Freie Presse and the Indiana Staatszeitung, was one of the only German-language papers in Indiana to survive the anti-German sentiments prevalent during World War I. The paper continued publication until 1927.

Fort Wayne is not the only newspaper hub in Allen County. There’s a few smaller towns where newspapers were published, particularly in the eastern part of the county. In Grabill, there was the bi-monthly Cedar Creek Courier (1949-1981) and the weekly Review (1907-1918), which emphasized local news. Monroeville provided its newspaper-reading public with the weekly Breeze (1883-1944), originally called the Democrat (1869-1883), and the News, which began in 1946 and still runs as a weekly today. Finally, New Haven published some key papers for the county, including the Allen County Times, founded in 1927 and still publishing today.

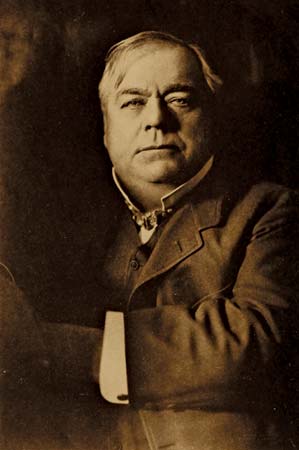

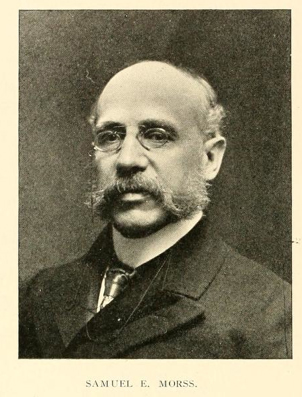

Alongside all of its newspapers, Fort Wayne produced two of the twentieth century’s most prominent publishers. William Rockhill Nelson, born in Fort Wayne on March 7, 1841. Nelson studied at Notre Dame (he did not graduate) and earned admittance to the bar in 1862, before he decided to enter the newspaper business. He and his business partner Samuel E. Morss purchased the Fort Wayne Weekly Sentinel in 1879 and published it for around nine months. From there, Nelson followed the old maxim “go west young man,” and he and Morss moved to Kansas City, Missouri. Nelson and Morss founded the Kansas City Evening Star in 1880. By 1885, the newly-renamed Kansas City Star became one of the Missouri’s most widely-read papers in the state. By the time of his death in 1915, Nelson’s estate totaled $6 million and his family ensured that his wealth supported the creation of the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, which opened to the public in 1933.

As for Morss, he sold his stake of the Star to Nelson within a year and a half. After traveling in Europe, he returned to the US and spent a few years as an editor at the Chicago Times. He came back to Indianapolis in 1888, to purchase and run the Indiana State Sentinel. He maintained his position with the Sentinel, with the exception of serving as Consul-General of the United States to France under President Grover Cleveland, until his death in 1903. Unexpectedly, he died after a fall from the third-story window of his Sentinel office, likely the result of a heart attack.

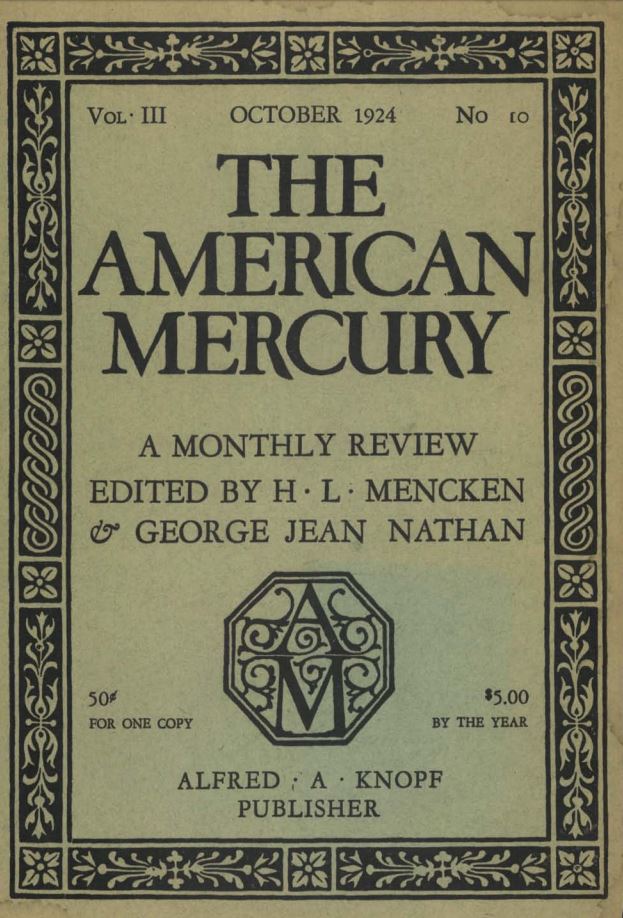

George Jean Nathan, another native of Fort Wayne, played a key role in the literary life of Americans during the 1920s and 30s. Born in 1882, Nathan spent his early years in Fort Wayne before he moved east, to study at Cornell University (he graduated in 1904). Nathan’s most enduring legacy stemmed from his relationship with noted journalist and provocateur H. L. Mencken. Nathan served as the co-editor with Mencken of the Smart Set from 1914-1923. They then founded the American Mercury, a magazine of literature, political commentary, and satire, in 1924. Nathan contributed drama criticism, particularly his views on playwrights such as Eugene O’Neill, Henrik Ibsen, and George Bernard Shaw, for the Mercury as well as his own publication, Theatre Book of the Year. He died in 1958.

Today, a few major papers serve the people of Allen County. Fort Wayne provides two daily papers: the Journal-Gazette, which publishes a paper version and maintains a website, and the News-Sentinel, celebrating 184 years of print publication. Both papers are published by Fort Wayne Newspapers, Inc., but maintain separate editorial staff. In New Haven, the Bulletin shares local news on its website without publishing a paper version. Grabill’s Courier Printing Company publishes the East Allen Courier, “a weekly free-circulation newspaper delivered to over 7,000 homes or businesses in Grabill, Leo, Harlan, Spencerville, and Woodburn.” In all, Allen County newspapers embody a rich journalistic heritage and continue to provide the news to over 355,000 residents.