Today, rural towns often have doctors with American Indian surnames. But in the 1800s, an “Indian doctor” meant something totally different.

For decades after the Civil War, so-called “Indian medicine shows” rolled through cities and country towns across the U.S. These shows were something like the medical version of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West. Leading them, there was usually a wild-looking doctor — typically a white man claiming to be Native American or at least to have studied herbal healing with “Indian medicine men.” What the shows really dispensed was exotic flare: banjo-playing minstrels, brass bands, even freak shows.

The traveling outfits also raked in thousands of dollars by touting medicinal cure-alls for common ailments, as Indian doctors announced their ability to cure practically all known ills — from dysentery, headaches and “private diseases” (venereal in nature) to dreaded cases of tuberculosis, cholera, and cancer. Elixirs were only part of the lure. These doctors often doubled as dentists and yanked rotten teeth by the thousands. In the days before anesthetics, brass bands covered up patients’ screams inside the wagon. Music and entertainment also helped drown out the protests of local doctors and dentists, whose business these shows cut in on.

While the heyday of the medicine shows came after the Civil War, the “Indian doctor” phenomenon goes back farther than that, piggy-backing off the dearth of professional doctors in pioneer settlements and the primitive state of “scientific” medicine itself. Southerners who moved to the midwestern frontier had often lived for a while in Appalachia, where white settlers took an interest in traditional medicine practiced by the Cherokee and Choctaw. German and Scots-Irish settlers also had a medical heritage of their own going back to medieval Europe.

(This early Indian Guide to Health [1836] contains some of the often bizarre knowledge gleaned from medicine on the Appalachian frontier. The author was an early Hoosier doctor, Squire H. Selman — alias “Pocahontus Nonoquet” — who studied with the Kentucky doctor-adventurer Richard Carter. Son of an English physician and a métis woman, Carter enjoyed one of the most thriving medical practices on the Ohio Valley frontier. Selman went on to practice medicine in Columbus, Indiana.)

It’s a curious fact that one of the first doctors in Indianapolis was a 24-year-old “Indian doctor” from North Carolina. The man also had an unforgettable name: Dr. William Kelley Frohawk Fryer. (In 1851, the Indiana State Sentinel thought his initials stood for “Dr. William Kellogg Francis Fryer,” but we sincerely hope that it really was “Frohawk.” That name appears on the cover of his own book.)

Dr. Fryer claimed to have studied medicine with Native Americans and was remembered by Indianapolis historians as an Indian doctor “of ancient memory.” Some of his repertory of cures, however, apparently came from “pow-wow,” an old form of Pennsylvania German faith healing. That practice was known as Braucherei or Spielwerk (spell-work) in the Pennsylvania Dutch dialect, and pow-wow practitioners (Brauchers or Hexenmeisters) drew on spells and folk remedies that probably go back to the world of Roman Catholic folk healing, forced underground in Germany after the Reformation. (The word pow-wow was either of Algonquin origin or a mispronunciation of the English “power” but had nothing to do with Native American medicine.) The first book on pow-wow, published by German immigrant Johann Georg Hohman in Reading, Pennsylvania, in 1820, anthologized many of these magical healings, talismans, and charms, based partly on occult “white magic” meant to ward off “black magic” or witchcraft. Pow-wow used esoteric words, sometimes from the Bible, as a form of healing and was explicitly Christian in nature, even reminding some of Jesus’ miracles accomplished via saliva. Brauchers allegedly cured livestock by putting magical words into their feeding troughs.

Pow-wow, which claimed to cure “both men and animals,” became an unorthodox form of spiritual medicine among Lutherans, Amish, Mennonites and Dunkers at a time when university-trained doctors were hard to come by even on the East Coast. Sometimes called “Christian voodoo,” pow-wow might even figure into the origin of the hex signs you can still see on barns. (It led to a “Hex Murder Trial” in 1929.) As a form of medical treatment, pow-wow’s heyday is long-gone, but it is still practiced on the sly in rural eastern Pennsylvania and was probably once part of folk medicine in the rural Midwest, wherever Pennsylvania Germans settled.

(Some scholars believe the hex tradition came out of pow-wow.)

In 1839, the year Dr. William Kelley Frohawk Fryer published his own Indian Guide to Health in Indianapolis, the Hoosier capitol city was just a few steps out of the wilderness. Fryer believed in “vegetable medicine.” He would probably have been able to find most of the roots and herbs he needed for medications in the swamps, bottomlands, and woodlands that still covered Marion County. There’s even some evidence that he provided medical treatment in exchange for plants. A clip from the Indiana State Sentinel in June 1886 states that he ran a place called “The Sanative House,” probably near his home on “South Illinois Street, near the Catholic school on Georgia.” But Dr. Fryer was long gone by 1886. In the late 1840s, the young doctor moved down to Mobile, Alabama, then to New Orleans, where he advertised his manual on health (printed in Indianapolis) for sale nationwide. Early front-page ads in the New Orleans Daily Crescent also carry glowing testimonials (maybe fictional) from his former patients back in central Indiana.

As the number of college-trained doctors and dentists back East grew after the Civil War, “Indian doctors” were squeezed out to the West and Midwest — where many claimed to have learned their trade in the first place, straight from Native American healers and shamans. (It’s hard to say how many of these claims are true, but a few of them probably are.) Yet “folk doctors” weren’t necessarily bad and provided the rudiments of medical care to some patients who couldn’t afford a university-trained physician, who simply had no access to one, or who (like African Americans) were even cruelly experimented on by the medical establishment.

J.P. Dunn, an early Indianapolis historian, wrote that Indiana was a “free-for-all medical state” until 1885. During the 1800s, American doctors and state and local officials gradually began driving “quack” doctors out of business (or at least out of town) by requiring all practitioners to hold medical licenses. The establishment didn’t always succeed at this. As early as 1831, legislators in remote Arkansas Territory tried to outlaw quackery. Their law, known popularly as the “Medical Aristocracy Bill,” was vetoed by the territory’s one-armed governor John Pope, a former Kentucky senator. Pope objected to it on the grounds that it violated “the spirit of liberty” and said: “Let every man be free to employ whom he pleases where he alone is concerned.” The governor also took a swipe at college-trained “professionals,” pointing out that

many who have gone through a regular course in the medical schools are grossly ignorant of the theory or practice of medicine. They are mere smatterers in the science. With a piece of parchment in their pocket, and a little superficial learning, they are arrogant, rash and more dangerous quacks than those who adopt the profession from a sort of instinct, or a little practical observation.

Pope may have been right. Whether educated or not, pioneer doctors sometimes killed whole families by accident. (My great-grandmother’s grandfather, one of the first settlers of Rosedale, Indiana, was orphaned in 1846 by a doctor who prescribed a deadly concoction of some sort to his parents and one of his brothers. As late as 1992, then, there was a Hoosier woman still living who had actually been raised by a man victimized as a young boy by pioneer medicine.)

In 1885, Indiana finally passed a law requiring doctors either to show that they had studied at “some reputable medical college” or had practiced medicine in the Hoosier State continuously for ten years preceding the date of the act. In April 1885, the Indiana Medical Journal endorsed this new law, saying: “It will probably make a few of the hundreds of quacks who now infest Indiana seek more congenial climes, and if enforced will prevent quacks from other states from settling within our borders.”

Yet the number of known Indian doctors operating in the state that year was low:

As J.P. Dunn pointed out, the tough question became: what was a “reputable medical college?” County clerks, not medical organizations, issued doctor’s licenses. Dunn wrote that since a county clerk only got paid if he issued a license, “he was usually liberal in his views” about the meaning of the word “reputable.” A state examination board for licensing doctors wasn’t set up in Indiana until 1897.

By then, one of the most outrageously colorful Indian doctors had already had his day in the Hoosier State and gone to his own grave.

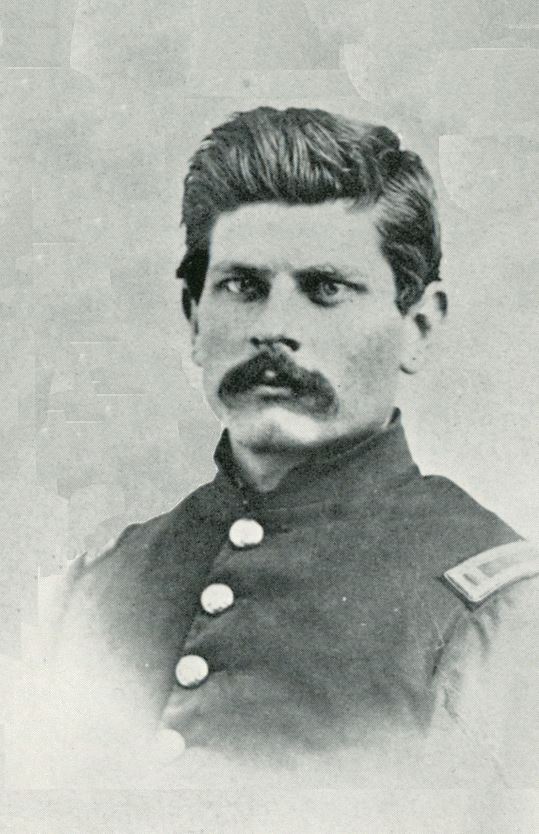

For a few summers in the early 1880s, Dr. J.I. Lighthall, “King of Diamonds,” crisscrossed the Midwest sporting a flashy, diamond-studded suit, selling his herbal remedies and often giving them away to the poor, while also earning notoriety as a “tooth-yanker.” Lighthall caught the interest of the press and annoyed local doctors in Terre Haute, Indianapolis, Fort Wayne, Richmond, Seymour and Columbus.

At the beginning of his Indian Household Medicine Guide, Lighthall claimed he was born in 1856 in Tiskilwa, a small Illinois River town north of Peoria. He announced that he was of one-eighth Wyandot heritage on his father’s side and had left home at age eleven to go out West to study botany with the Indians. If that’s true, in the 1870s the teenage Lighthall lived with tribes in Minnesota, Wyoming, Kansas and Oklahoma, picking up ethnobotanical knowledge on the Plains. He also grew out his hair, cultivating a look that some women, at least, found sultry and exotic.

By around 1880, Lighthall had set up shop in Peoria, Illinois. His mother apparently cooked barrels-full of his herb-, root-, and bark-based medicaments, then bottled them and shipped them by railroad or wagon. When it came to naming his drugs, he skipped the big Latin and Greek words of modern pharmacology and came up with colorful names like “King of Pain” and “Spanish Oil.” Some were probably cut with whiskey, cocaine, opium, and morphine. Lighthall also offered an array of 19th-century popular medicine’s omnipresent “blood purifiers” and “liver regulators,” miracle liquids commonly advertised in mainstream newspapers — partly to keep journalism itself afloat when subscriptions lagged.

As his business picked up, the doctor put together a brass band and went into makeshift dentistry on the street.

Educated skeptics abounded, but some of his herbal medications might actually have proven beneficial as “home remedies” for less serious ailments. The official medical view is that some patients were probably cured by the “placebo effect.” Curiously, one of the real health benefits of Lighthall’s medicine shows was that he got sick people to laugh.

Although the “doc” gave off an aura of the Wild West, most of his short career as an “Indian doctor” was spent in Indiana and Illinois. Lighthall typically rolled into a town and stayed for a few weeks or months, long enough to garner local notoriety. However angry the doctors and medical establishment got, “common folk” kept flocking to his medicine wagon. Dr. Lighthall’s entertainment troupe, newspapers reported, resembled a circus and was made up of about 60 “Spaniards,” “Mexicans” and “half-breeds” — and some Hoosiers from Fort Wayne.

Cleverly, Lighthall sympathized with the poor, sometimes handing out free medicine bottles wrapped in $10 and $20 bills to customers who couldn’t afford them. While the doctor won fame for such “charity,” thousands of others forked out their nickels and dimes for entertainment — money Lighthall would throw into the air to attract an even bigger crowd. Others came to have their teeth rapidly yanked, often for “free.” Yet in spite of all the freebies, within a year or two, Lighthall was rumored to be worth about $150,000 (maybe ten times that much in today’s money.) He wore clothes and a hat studded with valuable diamonds and cut an impressive appearance in public. Women were attracted to him. He put his gems on display at a Louisville jewel shop. A Kentucky hat store sold a line of Lighthall-inspired Texas hats.

Lawmen and doctors tried to do him in, but usually failed. A court in Decatur, Illinois, summoned him to appear in October 1883 for illegally practicing medicine there. Ironically, he had just come back to Decatur from Terre Haute, where “the Philistines” and Indiana’s “sun of civilization” drove him back over the state line.

The following summer, July 1884, Dr. Lighthall’s show rolled into Fort Wayne and camped out for a few months “near the baseball park. . . The joint resembles a circus.”

His tooth-yanking sometimes got him into legal trouble, as when he got sued for allegedly breaking a man’s jaw in Indianapolis during a complicated dental extraction. Lighthall’s apparent love for the ladies also turned public opinion against him. While camped out along East Washington Street in Indianapolis in 1885, he got booked by the cops for being “rowdy” at a “house of ill fame.” Locals accused him of trying to get two young girls near Fountain Square to run away with his troupe and “go on the stage.”

However dangerous and perhaps lecherous he might have been, Lighthall provided heavy doses of entertainment. On a trip to Chattanooga, Tennessee, in early 1885, the doctor got into a bloody tooth-yanking feud with a Frenchwoman engaged “in a similar line of business.” She was dressed as an “Indian princess.” The bizarre fight that followed deserves to be restored to the annals of history.

Lighthall may have engaged in just such a “contest” in Indianapolis:

After he left Louisville and the Jeffersonville area one summer, moving north to Seymour and Columbus, the Jeffersonsville News reported that local dentists were busy repairing the damage Doc Lighthall had done to Hoosier jaws.

For better or worse, the Indian doctor’s (and yanker’s) own days were numbered. By January 1886, he had headed south for the winter, encamping in San Antonio, where he was reported to be successfully filching Texas greenhorns of their greenbacks. Tragically, a smallpox epidemic broke out in un-vaccinated San Antonio that month. The 30-year-old’s medical knowledge couldn’t save him. He “died in his tent” on January 25, 1886. Several men from Fort Wayne who were performing with his troupe may also have succumbed to small pox.

News of his demise quickly flashed over Midwestern newspapers, in towns where he had become well-known in days just gone by:

Though rumor had it that Lighthall owned an expensive mansion and a medicine factory back in Peoria, he was buried at San Antonio’s City Cemetery #3, not far from The Alamo. Fittingly, there are bellflowers carved onto his gravestone:

He’s been forgotten today, but Dr. J.I. Lighthall’s fame briefly lived on, with at least one Hoosier writing to ask if he was alive or dead in 1888:

“Indian doctors” weren’t yet on their way out the door when Lighthall died in Texas in 1886. In 1900, in spite of efforts to regulate the practice of medicine, the patent medicine business was still reckoned to be worth about $80 million a year. Several major traveling shows thrived into the 1950s. By then, industrial pharmaceuticals and the discovery of antibiotics had launched medicine into a new era, but the entertainment aspect of the business kept it alive until radio and television killed it off.

Whatever the medicine shows did for the human body, they were definitely good for the soul, as the early 20th-century troupes helped fuel the rise of jazz, blues and country. In 1983, folklorist Steve Zeitlin and filmmaker Paul Wagner were still able to find some old medicine show performers in a rural North Carolina town — the subject of their documentary Free Show Tonight.

Contact: staylor336 [AT] gmail.com