Newspaper history is full of myths, “viral” stories, and tall tales. Folklore and journalism are often close cousins, especially the colorful “yellow journalism” that sold outright lies to rake in subscriptions. In the annals of Hoosier and American journalism, one persistent, tantalizing tale continues to baffle the sleuths at the Oxford Dictionary of Quotations.

Who wrote the famous slogan “Go west, young man, and grow up with the country”? It’s one of the great catch phrases of Manifest Destiny, an exhortation that echoes deep in the soul of Americans long after the closing of the frontier. But when you try to pin down where it came from, it’s suddenly like holding a fistful of water (slight variation on a Clint Eastwood theme) or uncovering the genesis of an ancient religious text — especially since nobody has ever found the exact phrase in the writings of either of the men who might have authored it.

“Go west, young man” has usually been credited to influential New York Tribune editor Horace Greeley. A New Englander, Greeley was one of the most vocal opponents of slavery. Antebellum Americans’ take on “liberal” and “conservative” politics would probably confuse today’s voters: a radical, Greeley famously opposed divorce, sparring with Hoosier social reformer Robert Dale Owen over the loose divorce laws that made Indiana the Reno of the nineteenth century. A religious man, he also promoted banning liquor — not a cause “liberal” politicians would probably take up today. Greeley helped promote the writings of Margaret Fuller, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Henry David Thoreau and even took on Karl Marx as a European correspondent in the 1850s. (Imagine Abraham Lincoln the lawyer reading the author of The Communist Manifesto in the Tribune!) In 1872, the famously eccentric New York editor ran for President against Ulysses S. Grant, lost, and died before the electoral vote officially came in. Greeley won just three electoral votes but was a widely admired man.

Though Greeley was always interested in Western emigration, he only went out west once, in 1859 during the Colorado Gold Rush. Originally a utopian experimental community, Greeley, Colorado, fifty miles north of Denver, was named after him in 1869. The newspaperman often published advice urging Americans to shout “Westward, ho!” if they couldn’t make it on the East Coast. Yet his own trip through Kansas and over the Rockies to California showed him not just the glories of the West (like Yosemite) but some of the darker side of settlement.

“Fly, scatter through the country — go to the Great West,” he wrote in 1837. Years later, in 1872, he was still editorializing: “I hold that tens of thousands, who are now barely holding on at the East, might thus place themselves on the high road to competence and ultimate independence at the West.”

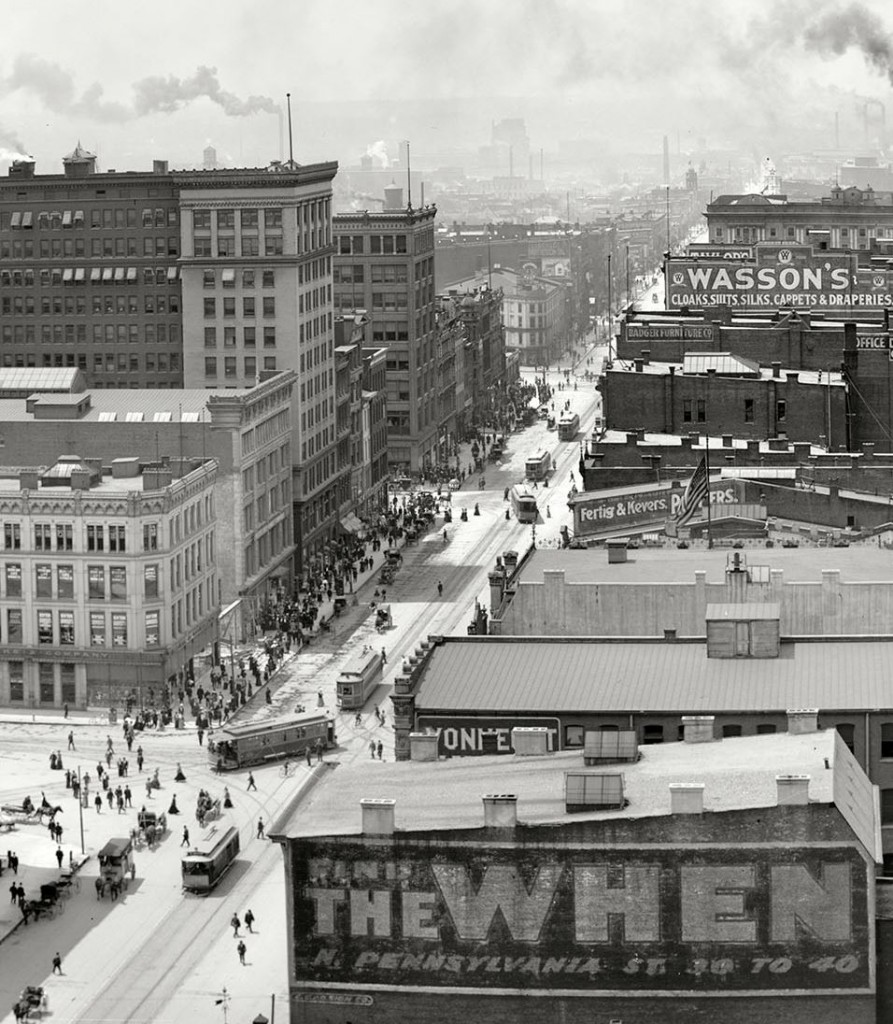

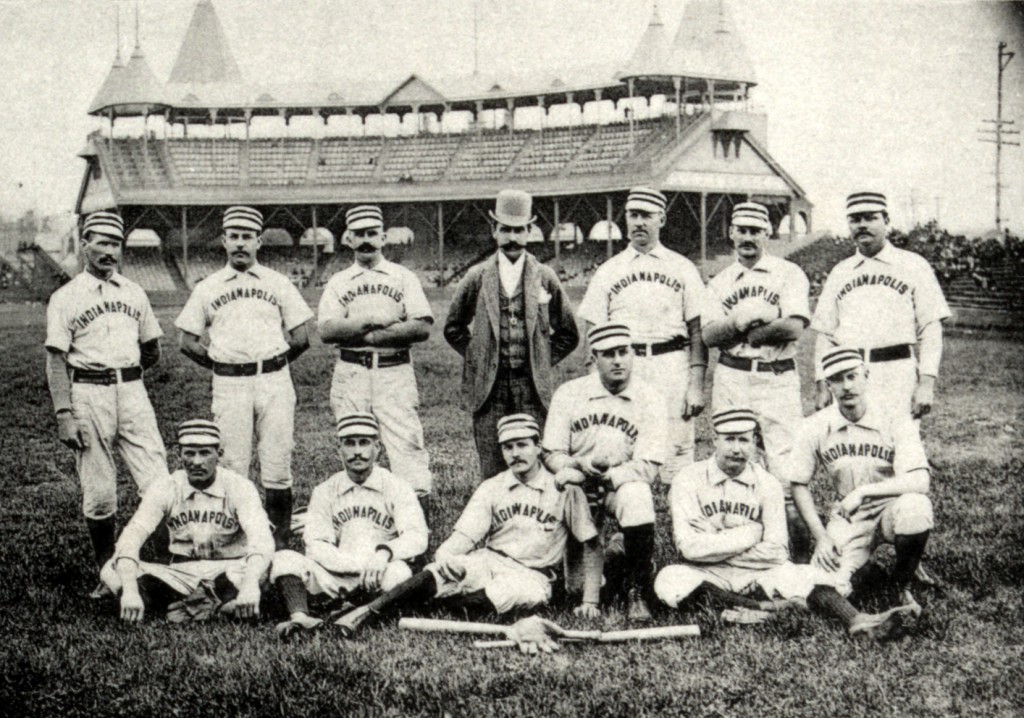

“At the West” included the Midwest. Before the Civil War, Indiana was a popular destination for Easterners “barely holding on.”

A major cradle of Midwestern settlement was Maine, birthplace of John Soule, Greeley’s competitor for authorship of the mystery slogan. As the logger, writer, and popular historian Stuart Holbrook wrote in his 1950 book Yankee Exodus, Maine’s stony soil and the decline of its shipping trade pushed thousands of Mainers to get out just after it achieved statehood in 1820. The exodus was so bad that many newspaper editors in Maine wrote about the fear that the new state would actually be depopulated by “Illinois Fever” and the rush to lumbering towns along the Great Lakes — and then Oregon.

One Mainer who headed to the Midwest in the 1840s was John Babson Lane Soule, later editor of The Wabash Express. Born in 1815 in Freeport, Maine — best known today as the home of L.L. Bean — Soule came from a prominent local family. His brother Gideon Lane Soule went on to serve as president of Phillips Exeter Academy, the prestigious prep school in New Hampshire. Though the Soules were Congregationalists, a likely relative of theirs, Gertrude M. Soule, born in nearby Topsham, Maine, in 1894, was one of the last two Shakers in New Hampshire. (She died in 1988.)

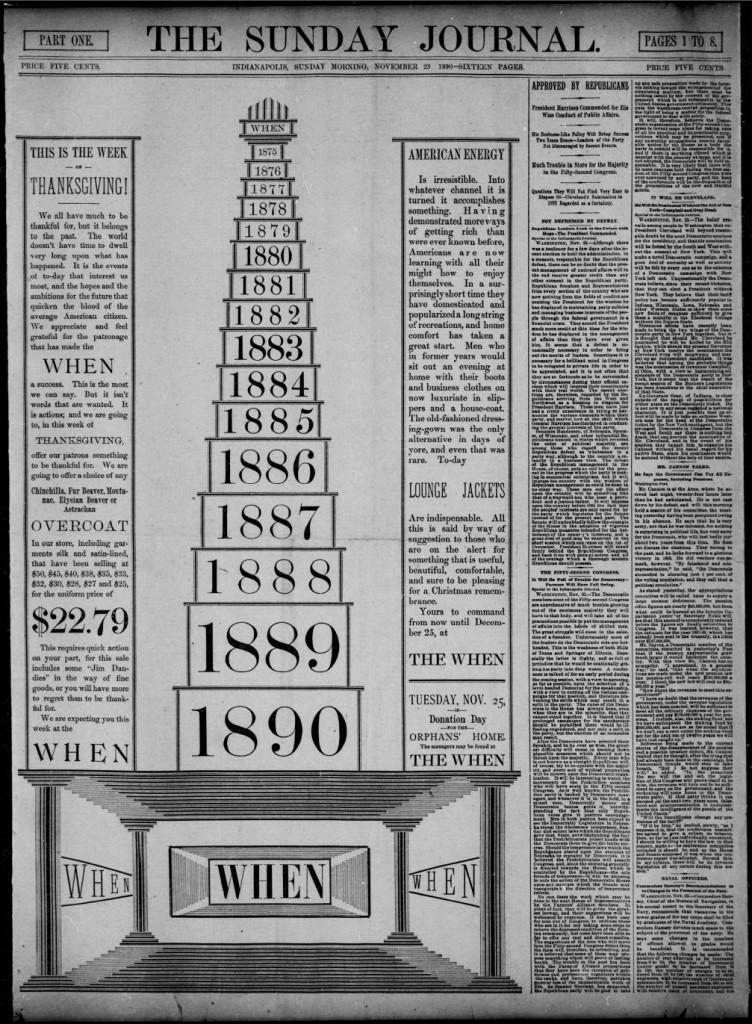

J.B.L. Soule — whom an 1890 column in the Chicago Mail claimed was the man who actually coined the phrase “Go west, young man” in 1851 — was educated at Bowdoin College, just down the road from Freeport. Soule became an accomplished master of Latin and Greek and for decades after his move west published poems in New England literary magazines like The Bowdoin Poets and Northern Monthly. A poem of his called “The Wabash” came out in Bowdoin’s poetry journal in August 1840, so it’s safe to assume that Soule had moved to Terre Haute by then. By 1864, he was still writing poems with titles like “The Prairie Grave.”

While Soule’s conventional, classical poetry might be hard to appreciate today, he was hailed as “a writer of no ordinary ability” by the Terre Haute Journal in 1853. Additionally, Soule and his brother Moses helped pioneer education in Terre Haute, helping to establish the Vigo County Seminary and the Indiana Normal School (precursor of Indiana State University) in the 1840s. J.B.L. Soule taught at the Terre Haute Female College, a boarding school for girls. The Soule brothers were also affiliated with the Baldwin Presbyterian Church, Terre Haute’s second house of worship.

John Soule later served as a Presbyterian minister in Plymouth, Indiana; preached at Elkhorn, Wisconsin, during the Civil War; taught ancient languages at Blackburn University in Carlinville, Illinois; then finished his career as a Presbyterian pastor in Highland Park, Chicago. He died in 1891.

He seems like a great candidate to be the author of “Go west, young man,” since he did exactly that. But it’s hard to prove that Soule, not Horace Greeley, coined the famous appeal.

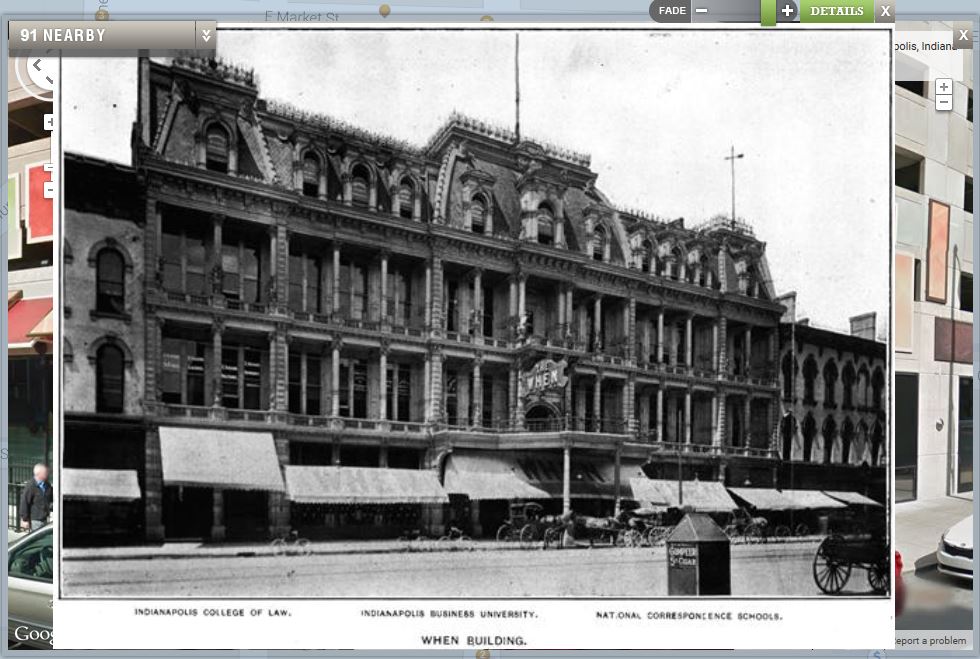

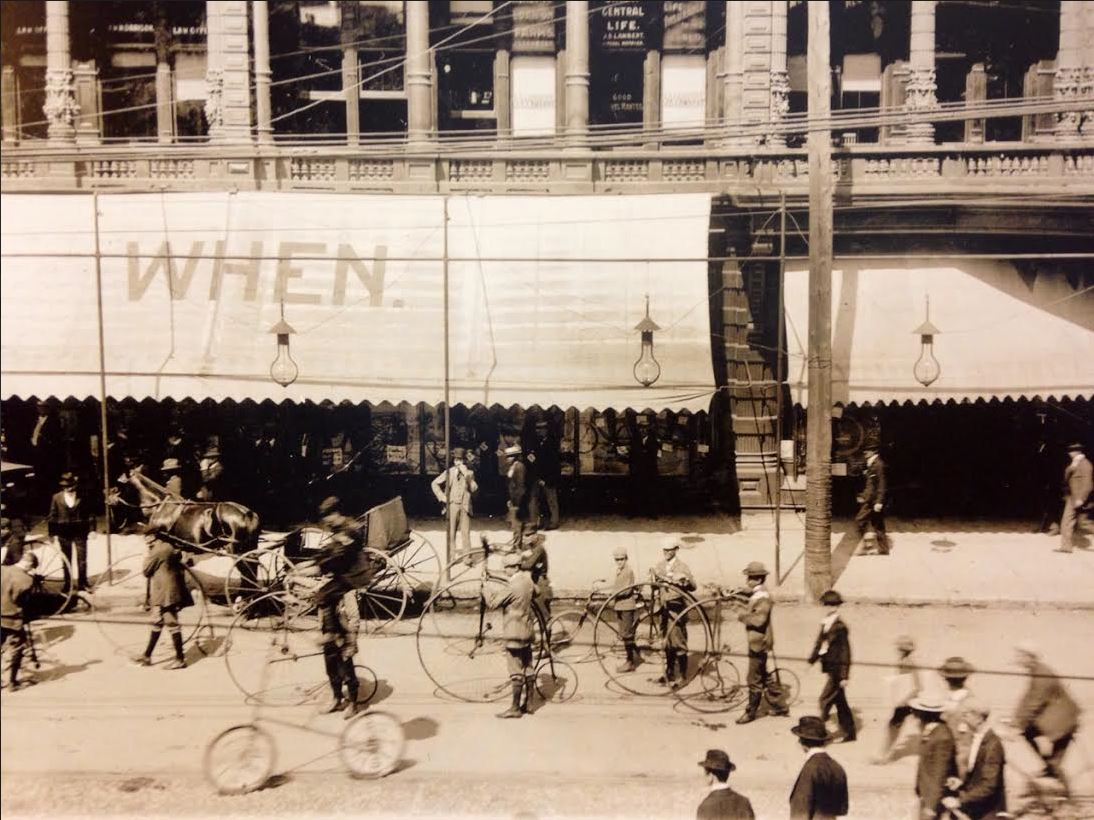

In November 1853, the Soule brothers bought the Wabash Express from Kentuckian Donald S. Danaldson, who had acquired it in 1845. Danaldson tried to make the paper a daily in 1851, but it failed in less than a year. John Soule and Isaac M. Brown worked as editors on Danaldson’s paper from August to November 1851, when it went under the name Terre Haute Daily Express. By the time J.B.L. Soule’s name appears on its front page for the first time on November 16, 1853, the paper was only being printed weekly and was called The Wabash Express. Soule, who also edited the Courier in nearby Charleston, Illinois, served as editor of The Wabash Express for less than a year.

Four decades later, in October 1891, an anonymous writer in the Chicago Mail reported a tale from an equally anonymous “old-timer,” told in an anonymous Chicago bar. The “Dick Thompson” of this story is Richard Wigginton Thompson. Originally from Culpeper, Virginia, Thompson moved out to Bedford, Indiana, to practice law, and settled in Terre Haute in 1843. During the Civil War, Dick Thompson commanded Camp Dick Thompson, a training base in Vigo County. Oddly for a man from almost-landlocked Indiana, he served as Secretary of the Navy under President Rutherford B. Hayes from 1877 to 1880. He died in Terre Haute in 1900.

Supposedly based on Thompson’s own memory, the story showed up in a column called “Clubman’s Gossip” in the June 30, 1890, issue of the Chicago Mail.

“Do you know,” said an old–timer at the Chicago club, “that that epigrammatic bit of advice to young men, ‘Go west,’ so generally attributed to Horace Greeley, was not original with him? No? Well, it wasn’t. It all came about this way: John L.B. Soule was the editor of the Terre Haute Express back in the 50’s, and one day in ’51, if I remember right, he and Dick Thompson were conversing in the former’s sanctum. Thompson had just finished advising Soule to go west and grow up with the country and was praising his talents as a writer.

“‘Why, John,’ he said, ‘you could write an article that would be attributed to Horace Greeley if you tried.’

“‘No, I couldn’t,’ responded Mr. Soule, modestly, ‘I’ll bet I couldn’t.’

“‘I’ll bet a barrel of flour you can if you’ll promise to try your best, the flour to go to some deserving poor person.’

“‘All right. I’ll try,’ responded Soule.

“He did try, writing a column editorial on the subject of discussion—the opportunities offered to young men by the west. He started in by saying that Horace Greeley could never have given a young man better advice than that contained in the words, ‘Go West, young man.’

“Of course, the advice wasn’t quoted from Greeley, merely compared to what he might have said. But in a few weeks the exchanges began coming into the Express office with the epigram reprinted and accredited to Greeley almost universally. So wide a circulation did it obtain that at last the New York Tribune came out editorially, reprinted the Express article, and said in a foot note:

“‘The expression of this sentiment has been attributed to the editor of the Tribune erroneously. But so heartily does he concur in the advice it gives that he endorses most heartily the epigrammatic advice of the Terre Haute Express and joins in saying, ‘Go west, young man, go west.'”

Though the story shook the foundations of the slogan’s attribution to Greeley, even on the surface the Chicago Mail piece is doubtful. What would Dick Thompson — no literary man — have to get J.B.L. Soule (a graduate of Phillips Exeter and Bowdoin College and one of the best writers in Terre Haute) to get over his modesty? The story also makes Thompson out to be a patriarch giving advice to the young. In fact, he was only six years older than Soule. It’s hard to imagine Thompson acting the father figure and “advising Soule to go west and grow up with the country” while they sat in a “sanctum” in Terre Haute — which was the West in 1851. Soule, from Maine, had already come farther than Thompson, from Virginia. And he kept on going.

The bigger problem is that there’s only a few surviving copies of the Terre Haute Express from 1851, and nobody has ever actually found the exact phrase “Go west, young man, and grow up with the country” in its pages or in any of Horace Greeley’s extensive writings. It would be understandable if the “old-timer” of the Chicago Mail or Richard W. Thompson got the date wrong after forty years, but researchers who have scoured all extant copies of the Terre Haute papers and Horace Greeley’s works have never found a single trace of the famous slogan in its exact wording.

J.B.L. Soule got mentioned in East Coast papers at least once: the Cambridge, Massachusetts Chronicle lauded his wit in their September 30, 1854 issue. So it’s plausible that a “Go west” column by him could have made it back East from Terre Haute. If so, it hasn’t appeared.

The exact phrase probably never got written down at all, but entered popular memory as short-hand for Greeley’s exhortations to migrate. Iowa Congressman Josiah B. Grinnell, a Vermont expatriate, used to be identified as the “young man” whom Greeley urged to get out of New York City and go west in 1853. But Grinnell himself debunked claims that he got that advice from Greeley in a letter. Even the oral advice Greeley gave Grinnell wasn’t the precise phrase we remember him for. Instead, he said “Go West; this is not the place for a young man.”

Wherever the phrase originated, as late as 1871, a year before his death, Greeley was still urging New Englanders and down-and-out men tired of Washington, D.C. to hit the western trails. However, the editor himself mostly stuck close to the Big Apple, venturing only as far as his Chappaqua Farm in Westchester County, New York during the summertime. While only at the big city’s edge, Greeley continued to play the role of western pioneer.