Digitized newspapers provide a rich boon to researchers about American medical history. From quack medicine ads to stories about diseases, from under-appreciated tales of wartime doctors to a gory list of “1000 Ways to Die,” old papers are gold mines.

Alcohol, of course, is part of medical history. Prohibition-era journalists were divided on whether America should turn off the tap. Indiana was one of several states to preempt the Federal ban on booze. the Volstead Act of January 1920, which officially ushered in Prohibition nationwide. As early as 1855, the Hoosier State tried out a liquor-ban. That law was repealed in 1858. Yet agitators kept on fighting against the bottle and the bier stein. In 1918, Indiana officially went “dry” again.

Nineteenth-century Americans were far heavier drinkers than today, and alcohol percentages tended to be higher. On-the-job drinking was allowed, sometimes even encouraged. Prohibitionists might seem prim today, but attempts to abolish beer and liquor were often tied to some real public health concerns. “Liberal” and “conservative” politics have changed over the last century. Many, perhaps most, anti-alcohol crusaders were progressives who also spearheaded the movement for women’s rights and child labor reform — and whose public health campaigns were frequently inspired by religious belief. Patriot Phalanx, a Prohibition Party newspaper started by Quaker Sylvester Johnson in Indianapolis, was a prominent mouthpiece.

Unfortunately, shutting down saloons, often had as much to do with racial, ethnic, and religious tension as it did with health concerns, and the whole law was primarily directed at the poor. Indiana’s powerful Ku Klux Klan was, at least officially, anti-liquor — partly because of booze’s association with German and Irish Catholics, whose leader at the Vatican the Hoosier KKK was virtually at war with during the 1920s, over issues like public schools. And the urban poor were very often Catholic.

One of the real perils of Prohibition was this: heavy drinkers and alcoholics still had a huge thirst to quench. Chronic tipplers had a few legal sources, like medicinal alcohol — and communion wine. Yet they often had fatal recourse to intoxicating liquids that nobody, of course, would normally drink. A fascinating if sober aspect of Prohibition lies in the story of the “beverages” they sometimes resorted to.

“Rotgut,” cheap, low-quality, potentially toxic liquor, was a common news headline even before 1920.

The “detox” problem — how to help out alcoholics — must have crossed the minds of Prohibitionists. But where alcohol was banned, death began to follow in its wake. And toxic liquor had become a global problem.

In 1914, Tsarist Russia banned the sale of alcohol except in restaurants, partly as a war measure to keep soldiers from getting drunk. Throughout the Russian Revolution, until 1924, in fact, the ban survived. But Russians’ sudden inability to get their famous national drink, vodka, led to many deaths. The Jasper Weekly Courier reprinted a litany of shocking tales about the lengths to which Russians would go to get a stiff drink during World War I. Forlorn men turned to guzzling perfume, cologne, khanza (red pepper mixed with spices and wood alcohol), and kvasok (a concoction of cider, yeast, wild hops, and snuff). Kvasok, incidentally, is the Czech word for “sourdough.”

American newspapers had been advertising the dangers of wood alcohol for years. Called methanol by chemists (not to be confused with methamphetamine), wood alcohol traditionally was produced like other spirits, through distillation. Ancient Egyptians had figured out the process and often used the resulting spirit — called the “simplest alcohol” — in embalming the dead. In the West, methanol was employed in a variety of industrial and other trades as a cleaner, in photography studios, and in tin and brass works. Around 1914, barbers were using it in a lotion called bay rum. Baltimore physician Dr. Leonard K. Hirshberg warned Americans that year about the danger of their barber causing them to lose their eyesight, since imbibing or inhaling wood alcohol could lead to blindness, even death.

Industrially, methanol is used as a feedstock in making other chemicals. Changed into formaldehyde, it is converted for products as diverse as paints, plastics, explosives, deicing fluid for airplanes, and copy-machine fluid. As the automobile age dawned, methanol came to be a component of antifreeze. Doctors as well as newspaper reporters were keen on reminding drivers and mechanics that too much exposure to the chemical, whether through breathing or touching, could cause blindness or worse. At the time Dr. Hirshberg was writing, there was probably a lot of wood alcohol around Indianapolis and South Bend, pioneer towns of the auto industry. Today, methanol is used as fuel in dirt trucks and monster trucks. It’s also the required fuel of all race cars at the Indianapolis 500, adopted as a safety feature after a deadly crash and explosion at the Hoosier track in 1964.

You can imagine the perils of chugging the stuff. Yet back in 1903, a couple in Columbus, Indiana, drank a deadly wood alcohol toddy, either by accident or through fatal ignorance of its effects. A year later, three artillerymen, thinking wood alcohol was a joke, died at Fort Terry in New London, Connecticut. In Philadelphia, the proprietor of a hat-cleaning shop who used the liquid in his trade had to mix red dye in it to try to deter his employees from stealing and drinking the stuff out back. The trick didn’t work, and he claimed “they’re used to it” now. It proved an effective means of suicide, as in the case of an 18-year-old girl in South Bend who fell in love with a high school teacher.

Some people said that refined wood alcohol smelled like old Kentucky rye. The toxic effects usually took a few hours to kick in, so group deaths often occurred after bottles of it were passed around among chums having a “drink orgy.”

After Congress passed the Volstead Act on January 17, 1920, the news was soon full of stories about desperate attempts to quench the literally killing thirst — and of unscrupulous efforts to profit off drinkers’ desperation.

A Brooklyn undertaker, John Romanelli, and four other men were indicted in 1920 on charges on selling wood alcohol mixed with “water, burned sugar and flavoring extracts.” They had sold the batch for $23,000 and the resultant “whiskey” caused “scores of deaths” in New England around Christmas-time and New Years’. In St. Paul, Minnesota, in March 1920, nine imbibers died in a 24-hour period.

Just two weeks before the new law went into effect, a Gary, Indiana, woman, Ella Curza, got a 60-day prison sentence and a $50 fine for possession of eighteen bottles of wood alcohol that she was allegedly peddling as an intoxicant. Hammond’s Lake County Times was already covering glimmers of the story — including the sale of methanol cocktails to unwitting men and U.S. soldiers stationed in Gary during the 1919 national steel strike.

By 1922, with the crackdown on hootch in full swing, the editors of the South Bend News-Times — a liberal-minded paper — issued figures on the estimated toll of wood spirits. “Wood alcohol is now killing 260 and blinding 44 Americans a year . . . In Pennsylvania the known deaths due to wood alcohol poisoning last year totaled 61 . . . Including unreported cases, wood alcohol’s death toll probably exceeds 1,500 a year.”

In New York, in the first six months of 1922 alone, 130 deaths and 22 cases of blindness were reported, a figure some officials thought “incomplete.”

Future Hollywood comedic actor Charles Butterworth, who was a reporter in his hometown of South Bend in 1922, penned a story about a certain medical claim: that alcohol-related deaths were actually higher after the Volstead Act came into effect than before. The St. Joseph County Coroner, Dr. C.L. Crumpacker, and other local medical men thought this statement was preposterous, however:

Prohibition clearly failed and would be lifted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in December 1933. Yet as one latter-day journalist, Pulitzer Prize-winner Deborah Blum, has discovered, the U.S. government — faced with the continuing thirst that led some Americans to crime and the more ignorant to varnish and perfume — decided to try out a different tactic.

Just before Christmas 1926, federal agents deliberately began poisoning alcohols typically utilized by bootleggers. In an attempt to deter the public — even scare them into staying dry — the agents essentially turned almost all alcohol into undrinkable “industrial” alcohol. Bootleggers tried to re-distill what the government had actively poisoned, which led to the deaths of (by some estimates) 10,000 people, deaths indirectly caused by the government’s “poisoning program.”

Blum, who has taught journalism at MIT and the University of Wisconsin and is a columnist for the New York Times, is no conspiracy theorist. In 2010, Blum authored The Poisoner’s Handbook: Murder and the Birth of Forensic Medicine in Jazz Age New York — a book made into a PBS/American Experience documentary in 2014.

If you or someone you know is dealing with alcohol-related issues, please visit http://www.alcohol.org/ for resources on how to get help.

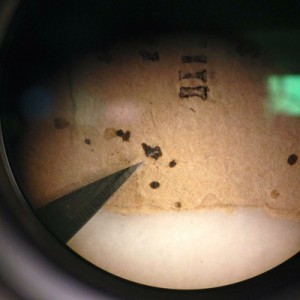

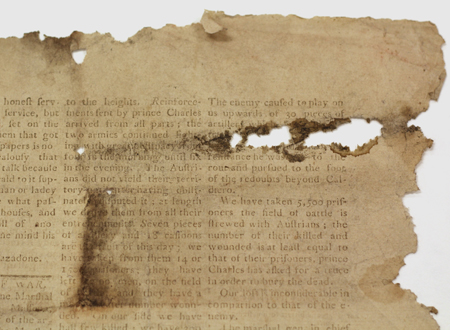

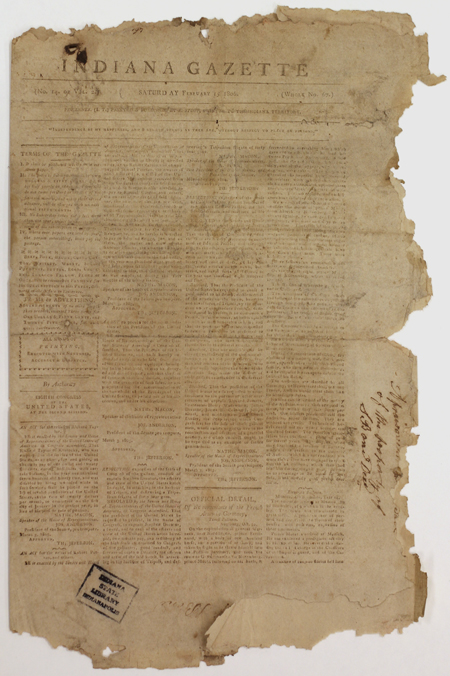

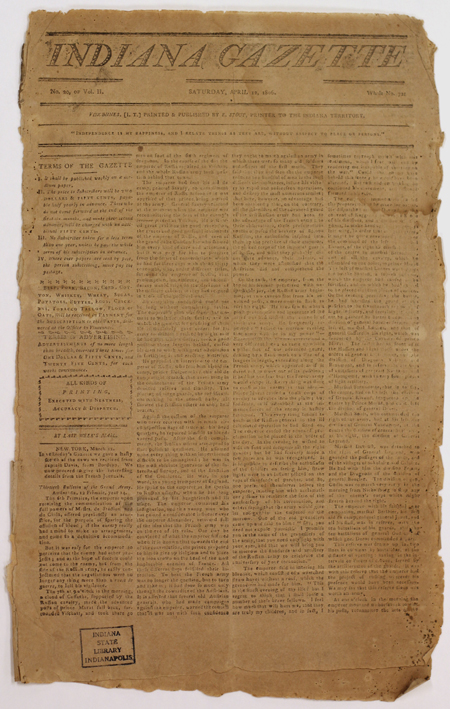

South Bend News-Times, May 19, 1920.

South Bend News-Times, May 19, 1920.