In a previous post, I featured an example of “text speak” published in the Vincennes Western Sun way back in 1849. Here’s a few more linguistic oddities from early Hoosier newspapers.

If you drink German beer from a bottle, you might have seen a label on the side saying something like “Brewed according to the German purity law of 1516,” a reference to the famous “Reinheitsgebot” that regulated the brewing of beer (i.e., only water, barley and hops could go into it.) But since 2016 marks the 500th anniversary of the German beer law, in the meantime let’s talk about a different kind of “purity.”

Denglish is a term used today in Germany, Switzerland, and Austria to refer to the mixing of “Deutsch” with “English.” Globalization has made English the dominant language on earth, and it’s not at all uncommon in Germany to hear things like ich habe den File downgeloadet (I downloaded the file) or catch someone ordering ein Double Whopper mit Bacon und Cheddar Cheese. Why? German certainly has perfectly good words for bacon and cheese. Maybe since McDonald’s isn’t German and is even an exotic novelty for some Europeans, asking for ein Doppelwhopper mit Speck und Cheddar-Käse just sounds too traditional or even too strange. Better to just leave it in English. (And, by the way, we don’t always translate, either: look at sauerkraut, apple strudel, bratwurst. . .)

Though English and German are related, outside the realm of food, not many words have ever come from modern German into modern English. Linguistic purists in Europe, on the other hand, go through “periodic bouts of angst“ (a German word!) about the influx coming from the other direction. (I wonder if this kind of angst exists in Sweden, where Paul Dresser’s On the Banks of the Wabash Far Away became a very popular song when it was translated into Swedish as early as 1919. You can listen to Barndomshemmet — a.k.a., “Childhood Home” — over on YouTube.)

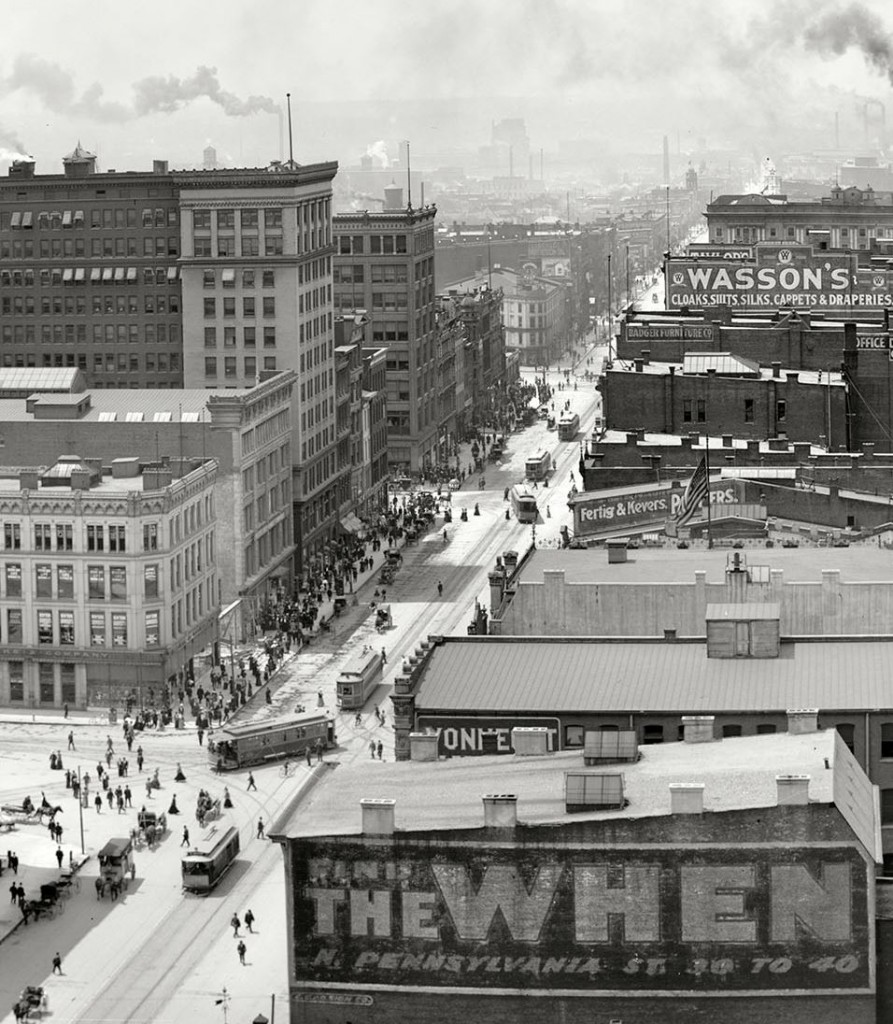

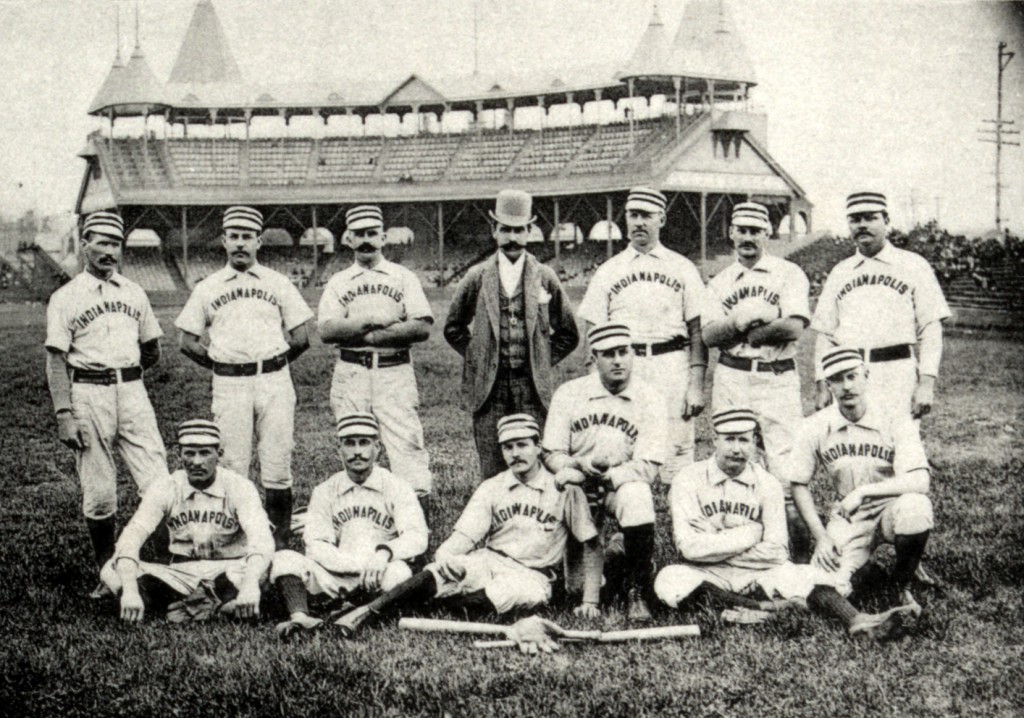

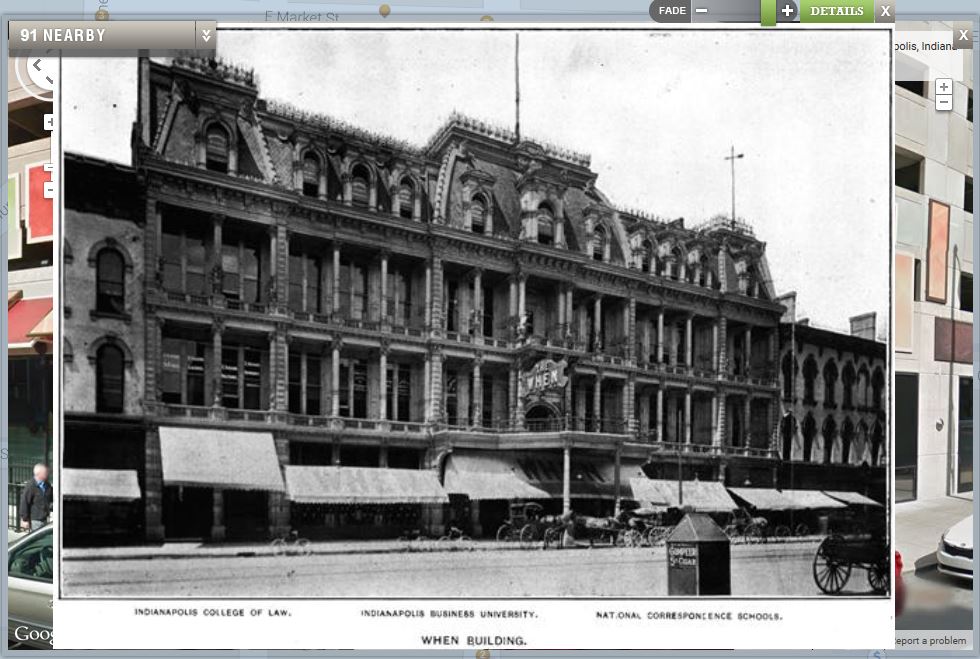

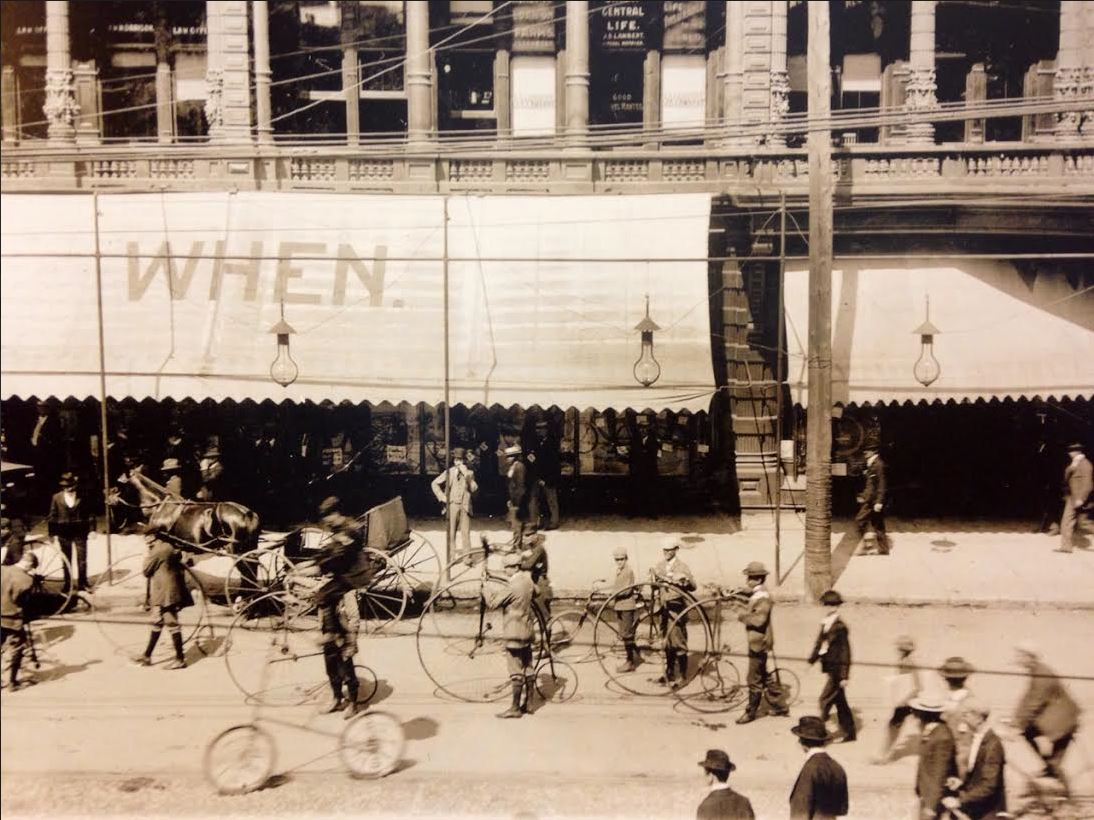

The influx is nothing new. In Indianapolis, Indiana, just after the Civil War, the town had a large German population and several important German-language newspapers — the Täglicher Telegraph (the weekly edition was called the Indiana Volksblatt und wöchentlicher Telegraph) and the Indiana Tribüne.

The Tribüne survived until World War I, when anti-German feeling helped silence it in June 1918. An advertisement in the Indianapolis Star on May 31, 1918, called on American boys to ““Kill Germans – kill them early, late and all the time but kill them sure.” Even Hoosiers with German names joined in the irrational hatred of everything German, like William Leib of Elkhart. Others supported the war against the Kaiser, like Richard Lieber — an immigrant from Düsseldorf, the founder of Indiana’s state park system, and a reporter for the Tribüne.

At one time, the Hoosier State also had a small number of other newspapers published in languages besides English. (The Macedonian Tribune began in Indianapolis in 1927 and is still published today in Fort Wayne. South Bend once had papers in Hungarian and Polish.) Today, La Voz de Indiana, a Spanish-language paper, is printed in the capitol city.

While I haven’t run across any examples of Indiana writers mixing English and German grammar, here are some great examples of Denglish from the early Hoosier newspapers. I culled these from random issues of the Indiana Tribüne and the Täglicher Telegraph between the years 1866 and 1910. Any issue from those days will turn up plenty of Denglish.

The old German Fraktur script can be a challenge to read if you’re not familiar with it, but if you can read any German at all, see if you can figure these out!

Meanwhile, enjoy this little bit of “Deutsches Theater in English’s Opernhaus.”

If you had Durst in Terre Haute in 1866, you might go to ein Saloon.

Habst du Hunger? (Und by the way, was sind Wahoo Bitters?)

This ad has more English than German in it. Buy ’em by the bushel crate:

While on Georgia St., you might be interested in grabbing some

Like seafood? Your slimy lunch was just delivered fresh all the way from Baltimore, even in the 1860s:

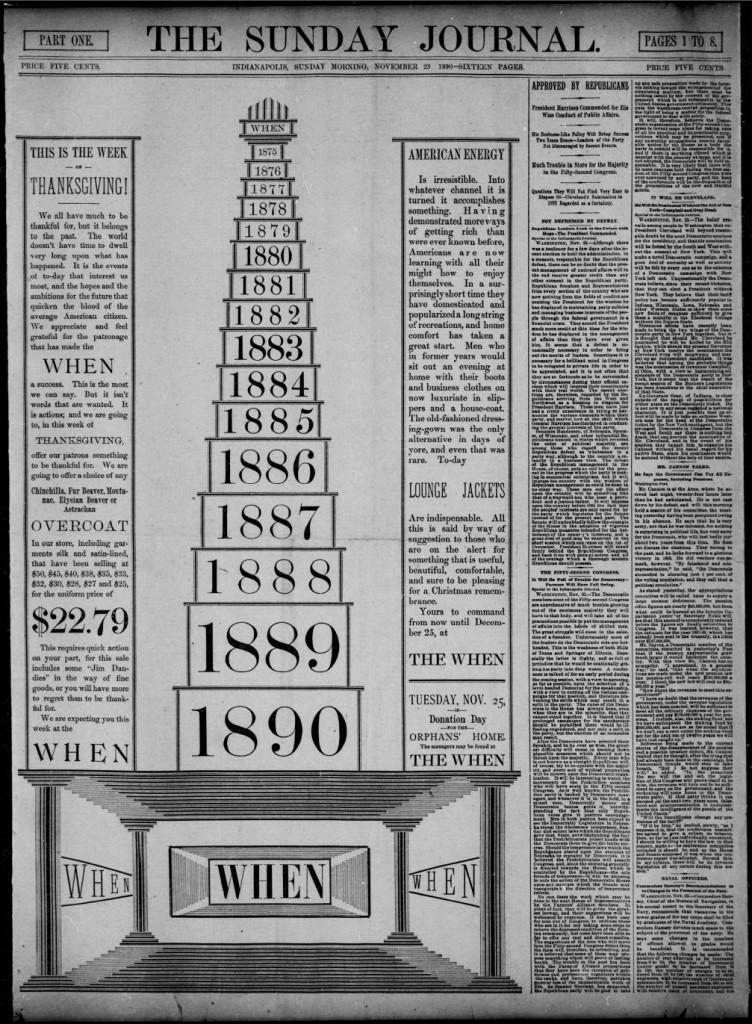

For dessert, treat yourself to something sweet. “All kinds” of this treat are available:

Rauchst du? It’s a bad habit, but if you’ve got to do it, make it a Hoosier Poet, and make sure it’s a real Havana:

Hausjacken on sale right now, $4.75:

Do you give your kids any of these before bed? Probably shouldn’t.

Und was trinken Sie? Before Prohibition, hundreds of breweries, many run by Germans and Czechs, dotted the American landscape. (A lot of these were rural areas, but city folk, of course, drank beer, too. The 1855 Lager Beer Riots in Chicago erupted partly because Mayor Levi Boone, descendant of Daniel Boone, didn’t like Germans boozing on Sundays. But he also he hated their radical politics and wanted to keep them from getting together at their watering-holes, where they talked about socialism and Chicago politics.)

At one time, the Terre Haute Brewing Company, founded in 1837 by German immigrant Matthias Mogger, was one of the largest beer-producers in the United States. The company’s nationally-famous beer “Champagne Velvet,” begun by Bavarian immigrant Anton Meyer, was recently resurrected by Upland Brewing in Bloomington. Germans enjoyed this and many other local beers on tap over a century ago in the Hoosier State:

Wait, too much drinking for you. Better make a special trip upstairs to see this technological wonder of the nineteenth century:

If you’re ready for another binge, hey, be family-friendly now and take them out on one of these:

Yes. That says “Big Picnic of the German Military Union.” Sound scary? Many German immigrants fought in the Civil War while serving in Hoosier regiments. This 1903 ad announces low rates for a train trip down South to erect the Indiana Monument at the Shiloh Schlachtfeld:

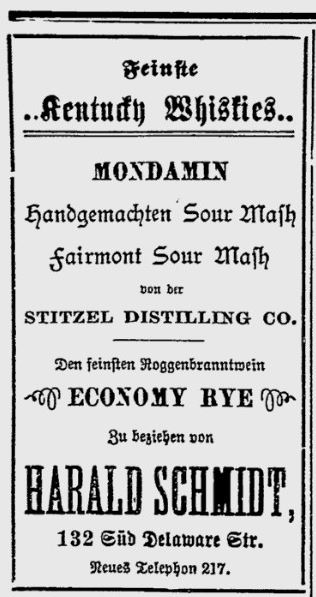

On your stopover in Paducah, grab a bottle of the finest Kentucky whiskey.

Plan on having the family portrait taken? Take the kids to Cadwallader and Fearnaught, Meisterphotographen, at their studio on Ost Washington Strasse in downtown Indy. And “bring the babies”:

Maybe you need a job. If you get an office job, you’ll also need some stationery.

(Office tape! In 1866!)

If you bite down too hard on one of those Star Pencils, or if ein Paper Clip gets stuck in your teeth, here’s a German-speaking Zahnärzte at your service:

There was even a female dentist in Indianapolis back in those days, Mary Lloyd, across from Fletcher’s Bank and the New York Store:

Dentists also dealt with problems caused by this stuff:

Got oil in your headlights? This brand is geruchlos (odorless):

ACHTUNG!! Watch out for das Manhole!

Keep your precious treasures safe. Bank with Mr. Fletcher:

Or keep your fortune safe at home with this hefty beast:

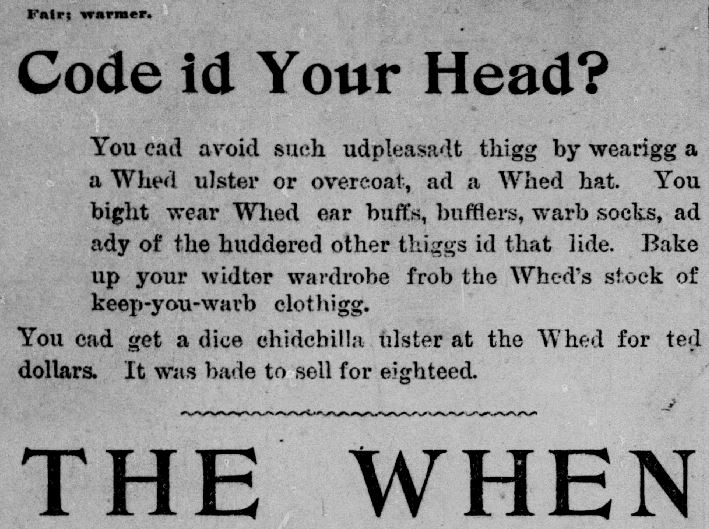

You can also protect your money by doing some bargain-shopping. Germans are famous for thrift, aren’t they?

Or skip shopping altogether and just take your kids to see Santa Klaus and let him provide the gift. Hier ist dein Ticket:

If Santa is in the neighborhood, that means it’s getting cold outside. Get a “honey comb quilt” or some serious old-school heating:

If you do get sick this winter, try one of these handy home remedies:

OK, that’s enough Denglish for me. I’m off on the Eisenbahn. And I’ll be traveling in style.

Run across any other great examples of Denglish? Have any personal stories to share? Bitte schicken Sie mir eine E-mail: Stephen Taylor at staylor336 [at] gmail.com

Like this:

Like Loading...