This article is based on a talk I gave at the Digital Public Library of America’s DPLA Fest conference on September 21, 2018.

Disclaimer: I am not a lawyer and this is not professional legal advice. This article is for educational purposes only. Please consult counsel concerning any potential digitization projects your institution is interested in pursuing.

Introduction

Good afternoon. Thank you very much for attending this session. I’m Justin Clark, Project Manager of Hoosier State Chronicles, our state-wide historic digital newspaper program at the Indiana State Library. We are a part of the National Digital Newspaper Program (NDNP), a joint venture between the Library of Congress and the National Endowment for the Humanities. To date, we’ve digitized nearly a million pages of historic Indiana newspapers, of which over 300,000 have gone into NDNP’s Chronicling America database of nearly 14 million digitized newspaper pages from across the county.

When digitizing historic newspapers for NDNP, one of the most important things to consider is whether the paper is under copyright. You could have picked the perfect title, had it approved by your institution, and completed all of the arduous work of collation, but if you don’t check its copyright status, your work could all be for naught. This is why a basic understanding of fair use, the public domain, copyright, and conducting copyright research is essential to any newspaper digitization project. This talk will provide a general overview of what fair use is, how it relates to newspaper titles, and how you can complete the necessary research to ensure your desired title for digitization is acceptable. Doing this work gives you not only an expanded scope of potential titles for digitization, but it also provides peace of mind that you won’t hear from any lawyers in the future, besides your institution’s counsel, of course.

Now, before we begin our stroll through copyright, I must say this. I AM NOT A LAWYER . . . nor have I played one on TV. This talk is only an educational overview of what I’ve learned about copyright research for digitizing newspapers. Other materials such as photographs, 3D objects, and written documents may not follow the same procedures or guidelines. It is imperative that you consult your institution’s legal counsel before making any concrete decisions to digitize anything. This saves you a visit from an irate lawyer who is upset that you’ve digitized materials that are still in copyright. And this little disclaimer saves ME a visit from an irate lawyer who got the call from the other one about copyrighted materials. In short, the only lawyer you want visiting your office should come from your institution. Now, with that out of the way, let’s start with fair use.

What Is Fair Use?

In the United States, copyright holders possess considerable legal rights for the protection of their intellectual property. This is a great thing – copyright holders can use their hard work to ensure an income and that scammers will keep their greedy hands off of work that doesn’t belong to them. But there are exceptions. One such exception to US copyright law plays a vital role in our emerging digital landscape: fair use. Fair use, according to the U.S. Copyright Office, “is a legal doctrine that promotes freedom of expression by permitting the unlicensed use of copyright-protected works in certain circumstances.” Essentially, fair use allows someone to use a copyrighted work for a completely different purpose than the copyright holder originally intended, which usually falls in the categories of “criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, and research.” These protections fall under Section 107 of the Copyright Act.

To determine whether or not a use of a copyrighted work is fair use, four general guidelines are followed. The first is the “purpose and character of the use.” Most of the time, if a person is using a copyrighted work for non-profit and/or educational purposes, it generally falls under fair use. This is especially the case if the use is “transformative” meaning that it “add[s] something new, with a further purpose or different character, and do[es] not substitute for the original use of the work.” In NDNP’s case, taking a newspaper which was originally created for immediate public consumption at a profit and transforming it into a digital historical artifact at no cost to the researcher usually falls under fair use. This guideline is not ironclad; sometimes, a copyright holder will object to their work being used in this way. Nevertheless, this guideline is generally applicable to NDNP and newspaper digitization as a whole.

Second, the “nature of the copyrighted work” is considered when determining fair use. This guideline is a little harder to pin down, but it basically means whether or not your use of a copyrighted work is too close to the original to be considered fair use. Specifically, “using a more creative or imaginative work (such as a novel, movie, or song) is less likely to support a claim of a fair use than using a factual work (such as a technical article or news item).” For our purposes, taking informational works such as newspapers and digitizing them for researchers changes the nature of the work, from a paid periodical into a free primary source document. In most cases, this would count as a fair use.

Third, the “amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole” plays a role in deciding fair use. In other words, if a person just blatantly copied the entirety of a copyrighted work and then sold it for their own benefit, it would not be fair use. However, for material that falls under the public domain (more on that below), recreating the entirety of the work is more than fine and falls under fair use. NDNP projects often have syndicated columns and cartoons that are copyrighted but the newspaper as a whole is not copyrighted. In those instances, the amount of non-copyrighted work outweighs the copyrighted work and the digitization of a newspaper is then considered fair use. We will unpack this more in the copyright research section.

Finally, fair use is determined by the “effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.” Put simply, does the use of a copyrighted work ruin its value in the marketplace? In the case of digitizing newspapers, a newspaper’s value stemmed from its original sale date, which was years or decades before. If a newspaper title is already in the public domain, its original market value is already gone and can be used by others in a myriad of ways. For NDNP projects, turning a newspaper into a primary source historical document does not destroy the market value of the original paper nor does it harm copyrighted works therein (syndicated columns and cartoons). Potential researchers are using the digitized newspapers for scholarly purposes, not for the resale of copyrighted material. As with the other three guidelines, the “market value” guideline is generally met.

This overview of fair use is not exhaustive. Definitely review material on fair use from the U.S. Copyright Office and the Copyright Alliance for more information.

What is “Public Domain”?

Alongside fair use, a clear conception of public domain is essential for working on NDNP-related projects. Works in the public domain, according to the Stanford University Library, are:

. . . creative materials that are not protected by intellectual property laws such as copyright, trademark, or patent laws. The public owns these works, not an individual author or artist. Anyone can use a public domain work without obtaining permission, but no one can ever own it.

A work enters into the public domain via three avenues: it can’t be copyrighted (i.e., titles, names, facts, ideas, government works), the creator of the work places it in the public domain, or its copyright term has expired. With NDNP, the last of these three is the most important.

Have you ever wondered why the vast majority of NDNP’s content, and most digitized newspaper content, ends around 1923? It’s for a very simple reason: all works published in the United States before 1923 are in the public domain. No copyright research is necessary for this material; it’s free and clear for you to use. However, NDNP announced in 2016 that it has expanded its date range for newspaper titles, from 1836-1922 to 1690-1963. Thus, post-1923 works are in the public domain if a copyright claim was never filed from 1923 through 1977 or if the copyright was never renewed from 1923 through 1963. All NDNP projects that follow these public domain guidelines will easily determine if their potential title is ready for digitization.

To learn more about public domain, visit these online resources from the Stanford University and Cornell University libraries.

Conducting Copyright Research

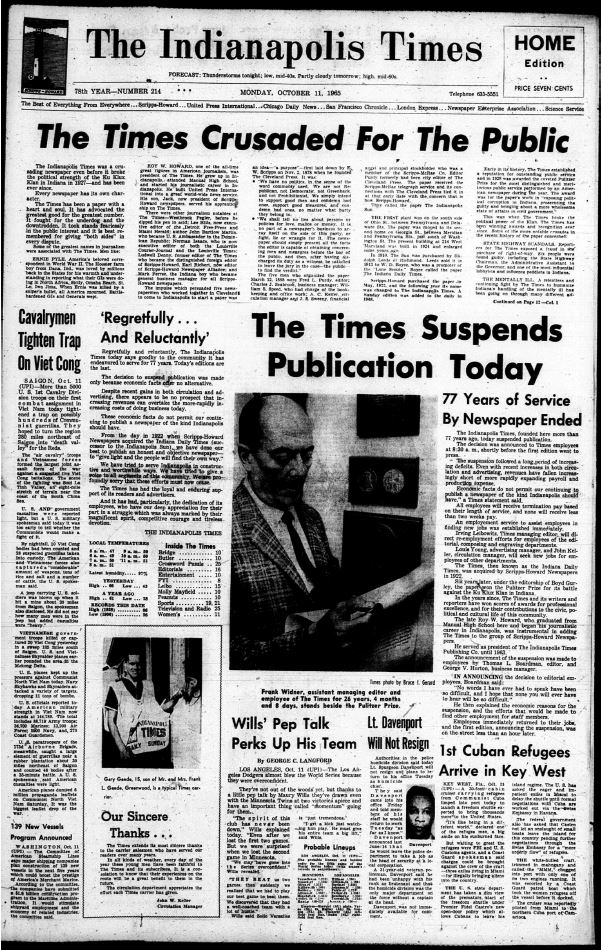

Now that you know how fair use and the public domain work, you can begin the necessary research to determine the copyright status of a newspaper title. Here in Indiana, we wanted to know the copyright status of one of Indianapolis’s premier papers of the 20th Century: the Indianapolis Times. The Times ran from 1888 (when it was titled the Sun) until 1965, a pretty impressive run for a daily metropolitan newspaper. From 1922 until its end, the Times was owned and operated by Scripps-Howard, a major publishing corporation based out of Cincinnati, Ohio. Knowing that such an influential publishing company owned the Times from 1922 until 1965 put an increased responsibility on us to make sure that the paper was either in the public domain and/or that its digitization would be considered fair use.

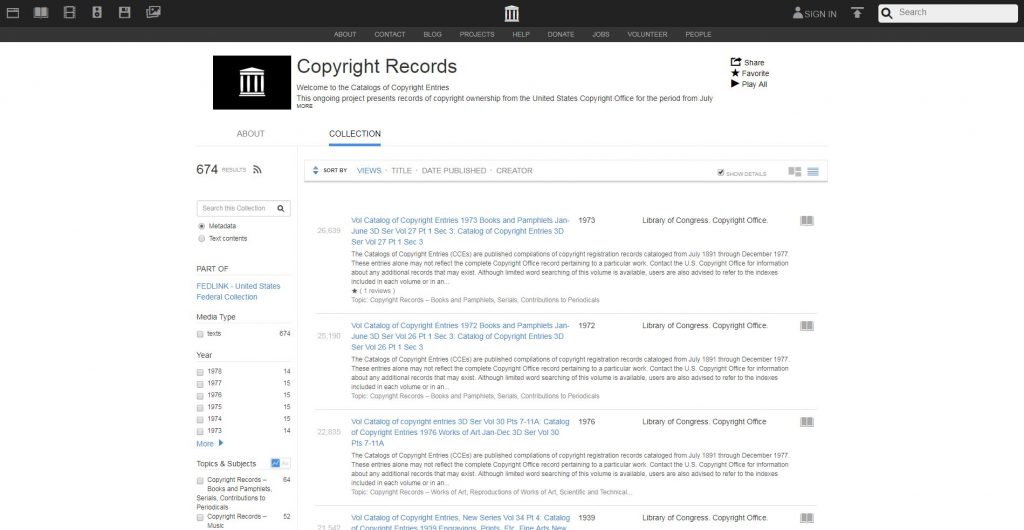

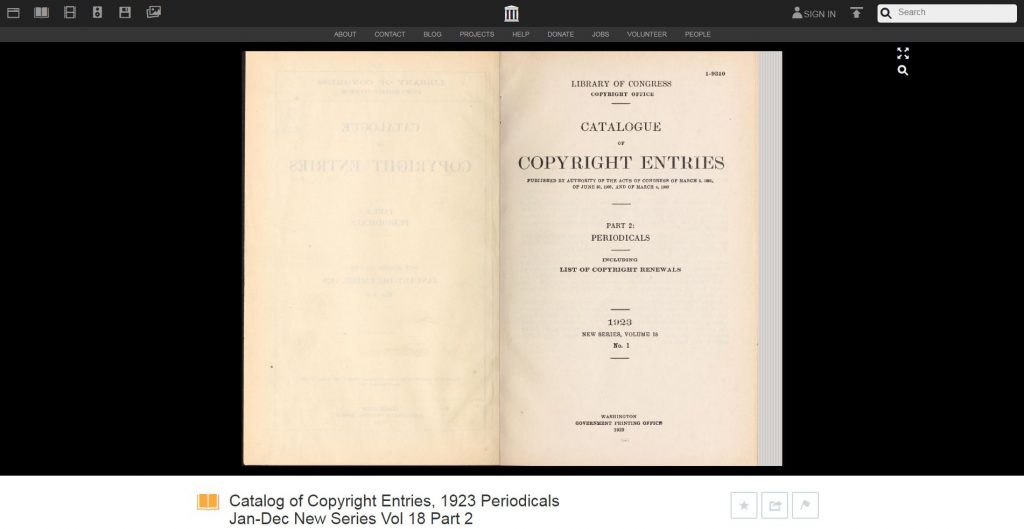

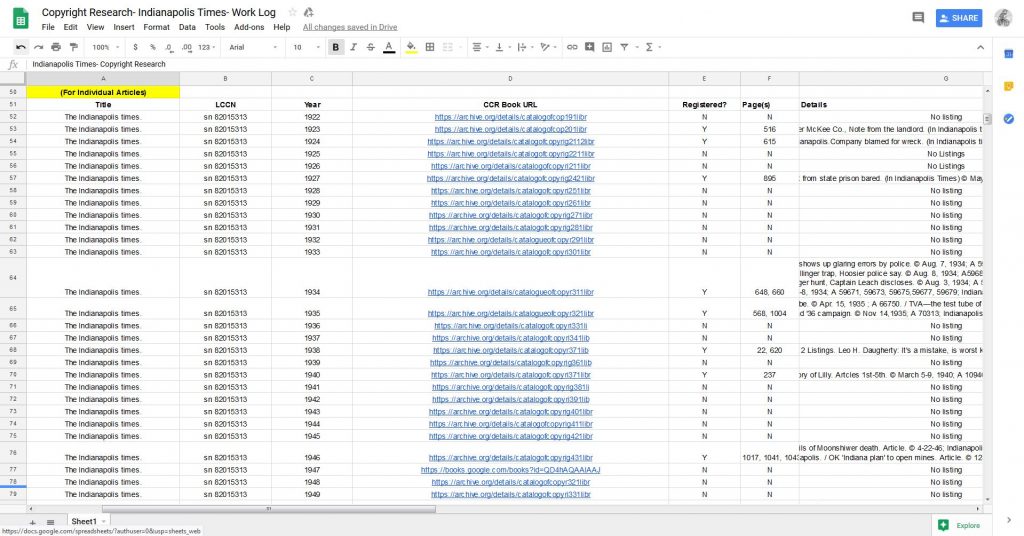

To figure this out, we examined its copyright as a complete title as well as the copyright of individual articles and/or syndicated content, to get a sense of how much material within the newspaper was copyrighted. Three resources allow you to complete this research: the Catalog of Copyright Entries (1906-1977) (published by the Library of Congress), the Public Catalog of Copyright Entries (1978-present) (online; published by the Library of Congress), and the Indianapolis Times newspaper microfilm collection (courtesy of the Indiana State Library).

The Catalog of Copyright Entries (1906-1977) is available at Internet Archive (www.archive.org) in a readable, PDF format. It comes with Optimal Character Recognition (OCR), so it is text-and-word searchable. To begin, view the 1923 Catalog of Copyright Entries, Part 2, which provides the copyright and copyright renewal for all periodicals published in the United States that year. For all the following years, look for the volume devoted to periodicals. In the search field, type the name of your title. If nothing comes up, search the catalog’s index for the title. If nothing is there, check the title within the book in the new copyright section as well as the renewal section. If nothing comes up, your newspaper title filed neither a new copyright nor a copyright renewal and it is in the public domain. Consult all remaining years of the catalog (in the periodical section) for any new copyright notices or copyright renewals. If you do find that your title was published with a copyright notice and a renewal from 1923-1963, it is not in the public domain and will remain under copyright for 95 years after the publication date. However, if the title was published from 1923-1963 with an initial copyright notice but was not renewed during that time, it is in the public domain and you are free to digitize.

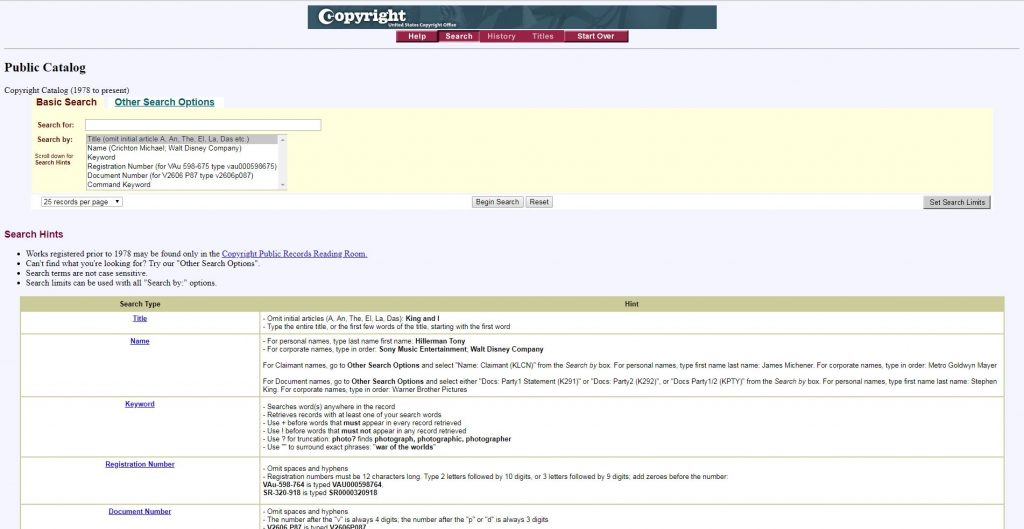

If you need to check anything after 1977, use the online Public Catalog of Copyright Entries, which covers 1978 to the present. This search is much easier than combing through the scanned versions at the Internet Archives. All you have to do is type in your title in the search bar; if you get no results, no copyright renewals were filed and you’re good to move forward. If there are copyright renewals, the title will remain under copyright for 95 years after its initial publication date.

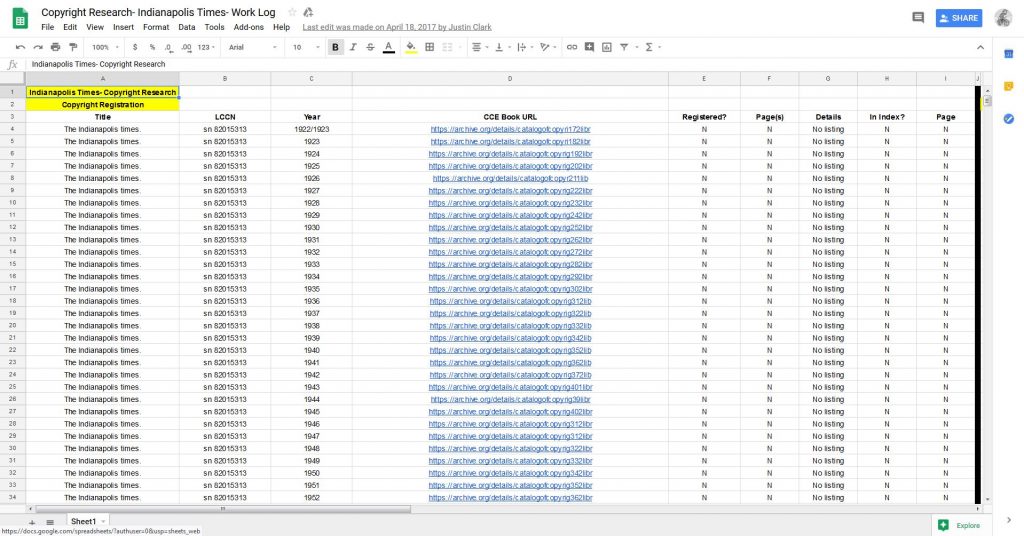

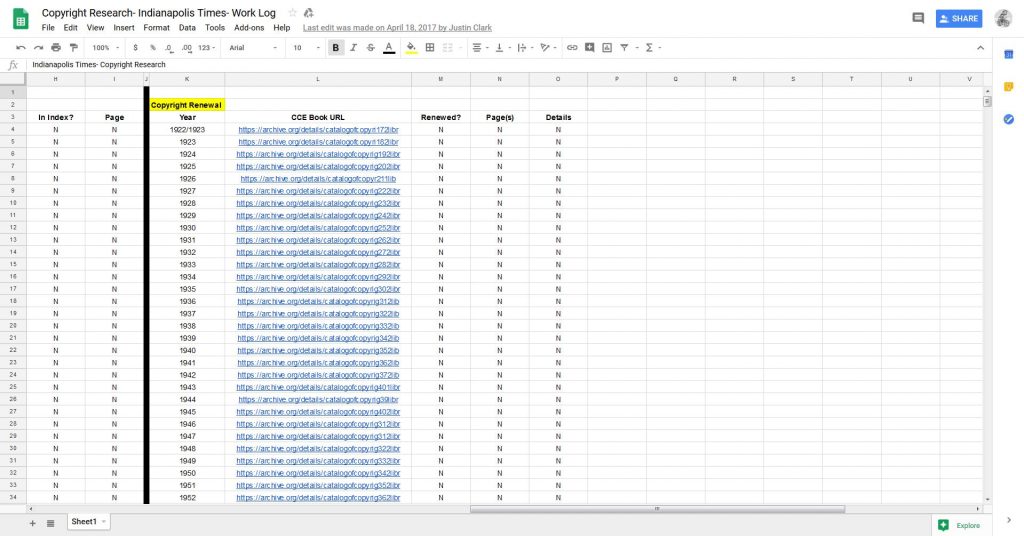

For our research, we started with 1922, the year that Scripps-Howard Newspapers purchased the Times and the final year it could have been in the public domain (this research was done in 2017, before the public domain covered 1923). According to listings in the Catalog of Copyright Entries and the Public Catalog of Copyright Entries, Scripps-Howard Newspapers never filed the Times for copyright between 1922-1965 or for subsequent renewals from 1965-present. Therefore, the Times as a complete newspaper is within the public domain and eligible for digitization.

But your search doesn’t end there! The copyright of individual articles and syndicated content also needs to be established. Library of Congress policy for NDNP has generally been that individually-copyrighted content within the “context” of an entire newspaper in the public domain is not a problem, so long as it doesn’t account for over 50% of the entire work. This rule is a recommendation and not an absolute policy. It is still up to you as an NDNP awardee, your institution, and your legal counsel to establish the proper procedures for such content.

Start with the scanned Catalog of Copyright Entries at the Internet Archive. However, instead of viewing the volumes devoted to complete periodicals, look at the volumes usually devoted to books or pamphets. These volumes include copyright information on individual pieces published in periodicals. Then search the online Catalog of Copyright Entries. Remember to check for both an original copyright notice and a copyright renewal. As with the newspaper title as a whole, if the article was published with a copyright notice and a renewal from 1923-1963, it is not in the public domain and will remain under copyright for 95 years after the publication date. Additionally, articles published from 1923-1963 with an initial copyright notice but no renewal are in the public domain and you are free to digitize.

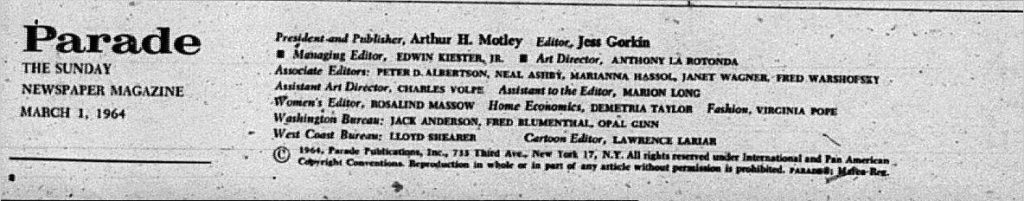

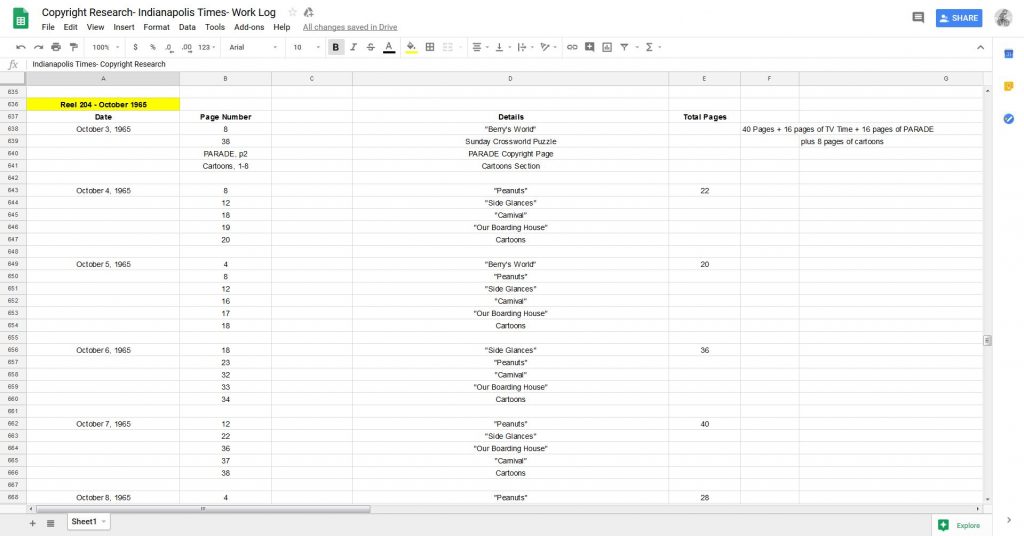

With our research of the Times, one type of syndicated content that showed up right away within copyright research was the Sunday supplemental, with PARADE magazine being an applicable example in the Times. From 1963-1965, PARADE was published with Sunday issues of the Times; it was copyrighted when it originally ran (and included in the Catalog of Copyright Entries) and was subsequently renewed (and included in the Public Catalog of Copyright Entries). As such, we decided not to include this supplemental in our NDNP deliverables. Regarding individual articles, we found 32 copyright listings in the Catalog of Copyright Entries from 1922-1965; only the initial copyright was listed and no renewals were found. These were then cross-referenced in the online Public Catalog of Copyright Entries to check for post-1978 renewals; none were found. These articles accounted for less than 10% of the entire field of research, way less than the more than 50% threshold for fair use. (So long as you consult your institution and its legal counsel.)

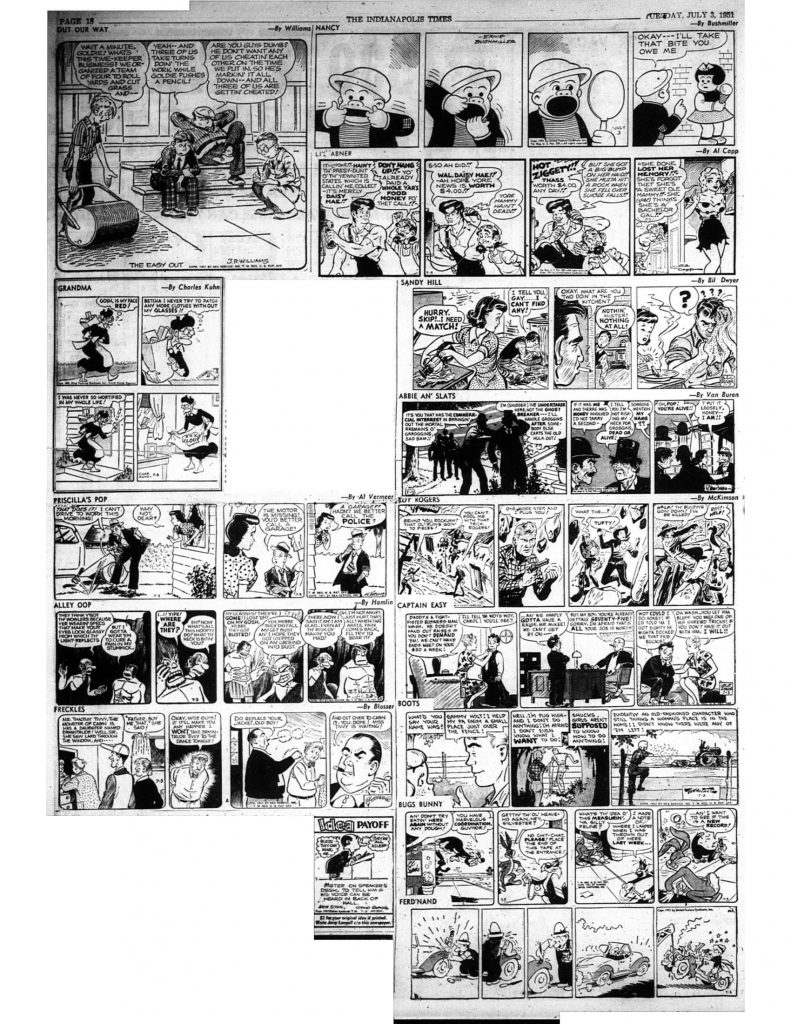

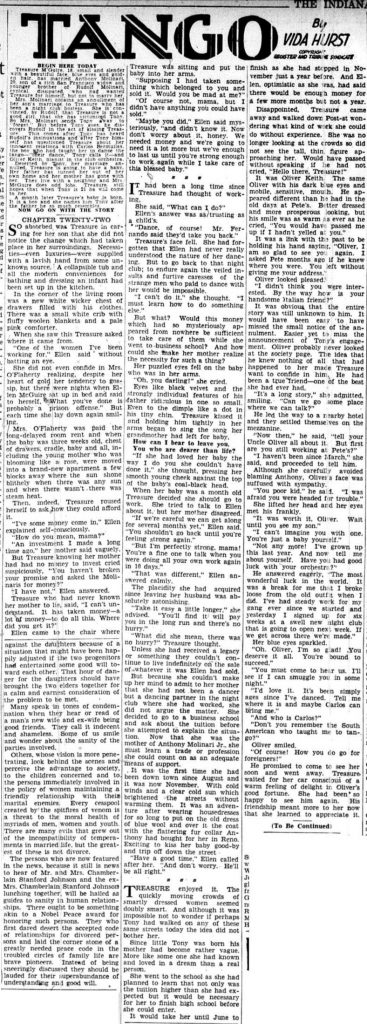

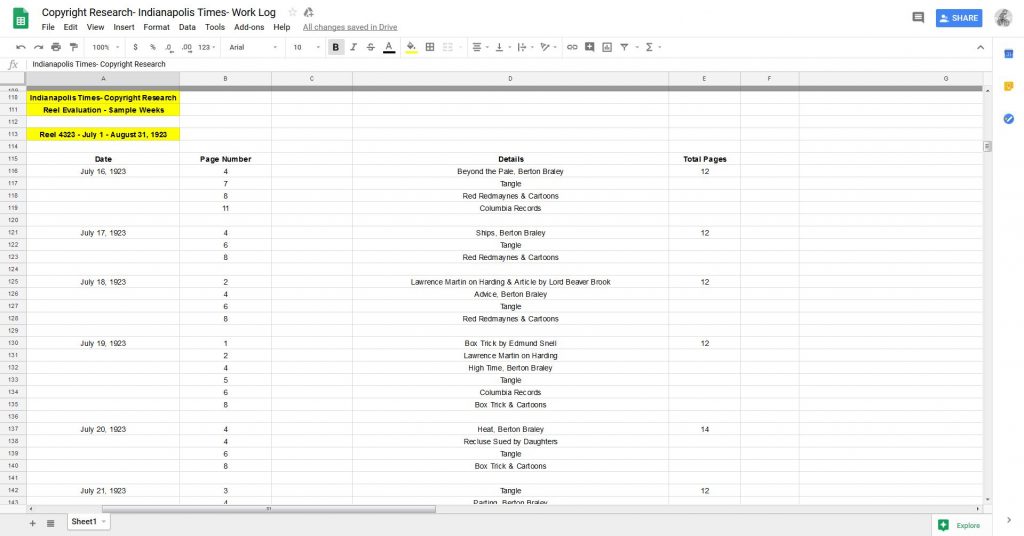

Now that you’ve thoroughly gone through the Catalogs, it’s also good policy to review the title’s microfilm. Here’s what we did. We chose three reels from each decade of the Times from 1923 to 1965 and scoured them for copyrighted content. We concluded that the vast majority of material on these reels fell within the public domain, in keeping the Times’s policy on copyright. As for what was copyrighted, it was mostly advertisements for still-existing products (Columbia Records, Bayer Aspirin), syndicated cartoons (individual cartoons scattered throughout the paper as well as one full page an issue), serialized fiction, and syndicated columns. These materials contained a copyright symbol and text, indicating its status. We concluded that these entries constituted a small minority of the newspaper content and largely will not affect the proprietary interests of the copyright holders (seeing as the content in question was digitized from second-generation microfilm, which itself come from first-generation preservation microfilm based photographed pages; the loss in resolution and quality should not urge copyright holders to pursue legal action). You can do more or less with your title’s microfilm than we have, but this should be enough to establish a broad consensus on your title’s copyright status.

Once you’ve done all of these procedures, it is best to draft a full report of your research and findings to your NDNP advisory board, as well as your institution’s legal counsel. Make sure to be as detailed as possible – this ensures they fully understand what you’ve done and saves you the trouble of having to answer a bunch of follow-up questions. For our research on the Times, I and my project director drafted our report and then sent it to the aforementioned parties. From there, we received approval to digitize the Times.

One more tip for your research: make sure to keep detailed notes of everything you do. You will be going through a lot of newspapers, so it will help you keep things straight. It also provides a paper trail that your institution’s leadership and legal counsel can consult if necessary. I suggest using Google Sheets and Docs to complete this research. It will be in the Cloud and can be easily shared with anyone who would like to see it. If Google is not your fancy, use Microsoft Office and back up your work to the Cloud or another hard drive. You don’t want to work diligently for months to have all of it lost because of computer issues.

Conclusion

Digitizing newspapers has been one the most rewarding things I’ve worked on in the public history and cultural heritage space. Seeing a title like the Indianapolis Times digitized and made available for researchers to use, for free, has been a real privilege. But all of this could not have happened without doing the long and often-tedious work of copyright research. Researching a title’s copyright ensures that it is free and clear for you to digitize—and a lawyer from King Features or PARADE magazine won’t come knocking on your door. Yet, copyright research can also be very rewarding. It gives you a big-picture view of the title you’re considering for digitization. You’ll see who its original audience may have been, the kinds of stories they covered, and how it fits in the context of your state’s, and the country’s, history. This, among many other things, makes copyright research worth it. Thank you.