Indiana, a state claimed as “free” from its statehood in 1816, was nevertheless the 7th highest non-southern state with racial terror lynchings, with 18 separate incidents. When searching through Indiana newspapers, many stories emerge of outlaw vigilantes who terrorized and brutalized African-Americans, sometimes for nothing more than alleged crimes. Since many were lynched before they received equal justice under the law, many of their lives ended tragically through injustice under the lariat.

To learn more about Flossie Bailey, check out Nicole Poletika’s article from the Indiana History Blog.

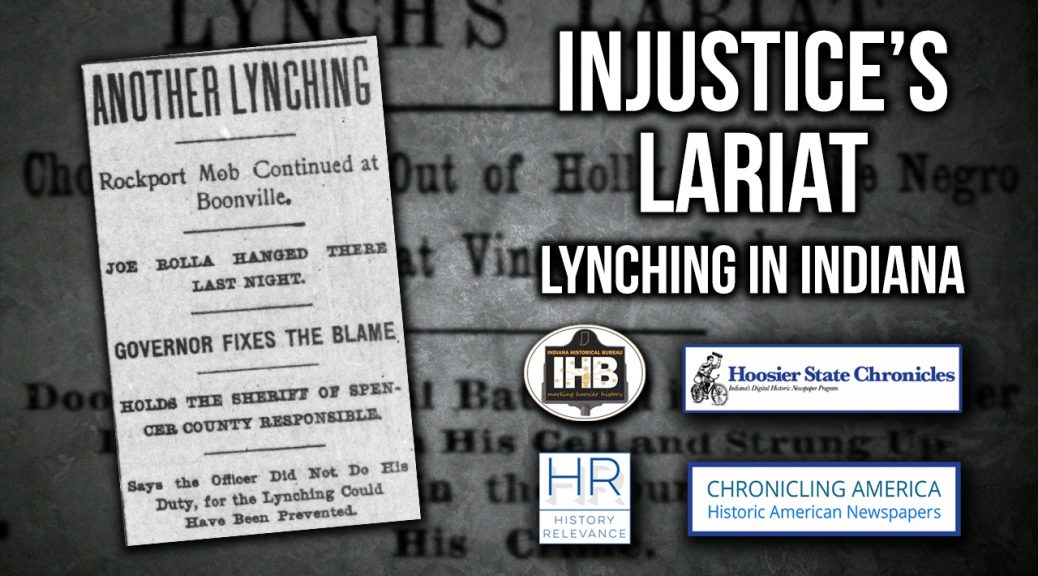

Learn about other stories of lynching at Chronicling America (https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/) and Hoosier State Chronicles (www.hoosierstatechronicles.org).

Learn more Indiana History from the Indiana Historical Bureau: http://www.in.gov/history/

Visit our Blog: https://blog.newspapers.library.in.gov/

Learn more about the history relevance campaign at https://www.historyrelevance.com/.

Please comment, like, and subscribe!

Credits:

Written and produced by Justin Clark.

Footage from CNN, PBS Newshour, the Guardian, Dryerbuzz, and the Equal Justice Initiative

Photo by Citizensheep on Foter.com / CC BY-NC-SA

Photo by Fraser Mummery on Foter.com / CC BY

Photo by Claire Anderson on Unsplash

Music: “Ether” by Silent Partner, “Dramatic, Sad Ambient Song” by MovieMusic, and “Slow, Dramatic, Acoustic Song” by MovieMusic.

Full Text of Video

The United States, regardless of its successes, has a dark past that we still grapple with today. A new and powerful reminder to the injustice of the American past is the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, located in Montgomery, Alabama. On the six-acre memorial stand “800 corten steel monuments, one for each county in the United States where a racial terror lynching took place. The names of the lynching victims are engraved on the columns.” Additional, blank monuments have been added to include yet-undiscovered lynching.

The monument was the brainchild of the Equal Justice Initiative, a nonprofit “committed to ending mass incarceration and excessive punishment in the United States, to challenging racial and economic injustice, and to protecting basic human rights for the most vulnerable people in American society.” In its 2017 report, “Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Terror,” the EJI “uncovered more than 4,400 victims from 1877 to 1950, including 800 previously unknown cases.”

While the vast majority of lynching occurred in the south, a sizable portion occurred in the Midwest. Indiana, a state claimed as “free” from its statehood in 1816, was nevertheless the 7th highest non-southern state with racial terror lynchings, with 18 separate incidents. One way historians have uncovered these horrific crimes is with newspapers. When searching through Indiana papers, many stories emerge of outlaw vigilantes who terrorized and brutalized African-Americans, sometimes for nothing more than alleged crimes. Since many were lynched before they received equal justice under the law, many of their lives ended tragically through injustice under the lariat.

One of the earliest lynchings in Indiana newspapers was chronicled by the Marshall County Republican on November 23, 1871. Three African-Americans, whose names were only given as “Johnson, Davis, and Taylor,” were accused of the murder of the Park family in Henryville, Clark County. Matthew Clegg, “a shystering lawyer” from Henryville, had a dispute with the Parks and when he likely had them murdered, he pushed the blame to the three local African-American men. When the grand jury couldn’t find enough evidence to indict them, the local vigilance committee took matters into their own hands. They broke through the jail, grabbed the three men, placed nooses around their neck, and dragged them through the street. They were then strung up next to each other on a tree. The Republican described their bodies in painful detail; Taylor’s description was the most gruesome: “His form was nude, save the slight remnants of a white shirt that was stretched across his lower limbs, while the hangman’s knot under his chin threw his head back in, a gasping movement, and his white teeth and distended lips grinned with a fiend-like scowl . . . .” It is unclear from the newspaper account if anyone was tried for the lynching.

In 1886, the Indiana State Sentinel reported the lynching of Holly Epps, who had been accused of the murder of a local farmer in Greene County. Around 12:50 on the morning of January 18, a “crowd of masked men” brandishing “sledgehammers and various other implements” descended on the Knox County jail. After failing to cajole the sheriff to open the door, the horde broke in, smashed through the jail cell, and dragged Epps out into the cold of night. Using the closest tree they could find, the mob strung Epps up and “for fully fifteen minutes he struggled for life, when death came to his relief.” The mob left his hanging remains on the courthouse grounds to be found by the county prosecutor. The sentiment of the citizens of the county, as recorded by the Sentinel, was one of satisfaction. “Citizens of all classes justify the lynching, and the moral sentiment is that the Greene County vigilants did a justifiable act in summarily removing the fiend from the face of the earth,” the Sentinel commented. The lynch mob were never prosecuted for their actions.

The 1889 lynching of Peter Willis in northern Kosciusko County received weird and contradictory coverage in the Indianapolis Journal. In its July 22, 1889 issue, the Journal ran a nondescript blurb about Willis’s lynching at the hands of a mob after he was charged with assaulting a little girl. The South Bend Tribune and the Indiana State Sentinel also ran stories with the same details. Then six days later, completely disregarding its previous coverage, the Journal published an editorial claiming “the assault and lynching episode referred to by the Sentinel [as well as the Tribune] never occurred, and is wholly an imaginary tragedy . . . .” The editorial further noted that “the only truth contained in the item is the superfluous information concerning the geographical location of Kosciusko county, which it says ‘is not in Mississippi or South Carolina,’ . . . and the further assertion that ‘it is the banner Republican county of Indiana.’” There’s nothing named Kosciusko in South Carolina and only a town named that in Mississippi; it was the Sentinel’s and Tribune’s way of saying it was in Indiana and highlighting that this can happen in the north. If the Journal thought they could drive a wedge of doubt through their phrasing, they were wrong. Furthermore, the fact that a county has Republican leanings says nothing about whether a lynching can occur there. This editorial was likely a political device to stave off criticism against a northern, Republican-leaning Indiana county. Sadly, it was misleading people about the unlawful execution of a person who had not yet been proven guilty in a court of law.

The beginning of the new century brought with it the same kinds of lawlessness that led to lynching, despite the Indiana General Assembly passing anti-lynching laws in 1899 and 1901. George Moore, an African American accused of assaulting two women and fleeing law enforcement, was lynched on the evening of November 20, 1902. He was “hanged to a telephone pole” in Sullivan County after a mob of roughly 40 men fought against the sheriff’s department. Moore had been a fugitive, attempting an escape to Illinois when he was captured by authorities in Lawrenceville, Illinois. The mob “beat him over the head with their weapons” before they hanged him. Governor Winfield T. Durbin was troubled by the situation and tried to stop it, but the requisite military and law enforcement officers couldn’t get there in time. It was another instance of mob violence instead of real justice, and the Indianapolis Journal said as much two days later in an editorial. “It is no excuse for mob law to say that the legal penalty in such cases is inadequate,” the Journal declared, “That is not for any mob or any community to say. If the penalty is not severe enough let the law be changed in a regular way, but while the law stands it should be observed.”

Over the next thirty years, lynching began to decline in Indiana; it had become a national issue with near-passage of a federal anti-lynching law. Indiana’s last-known racially-motivated lynching was in 1930, in Marion, when Abe Smith and Thomas Shipp were hanged by a mob. The crime was so horrific that the Indiana General Assembly, urged by Indiana NAACP President Katherine “Flossie” Bailey and others, passed another anti-lynching law in 1931. This law required that any sheriff serving in a county were a lynching occurred be suspended or dismissed as well as repealed many past statutes that limited the victims or their families legal recourse. It was a partial solution to a definite problem, one Indiana contended with for decades.

It is a common notion that lynching, much like racism, was a southern phenomenon in the United States. These select stories from Indiana newspapers illustrate just how wrong that notion is. The prejudice that people felt motivated them to take the law into their own hands, with disastrous consequences. Justice should be applied by democratic institutions, not by mob rule. That’s how we ensure the principle of equality under the law. But animus against African Americans was stronger than the virtue of justice. As a group of preachers declared in a 1910 article for the Indianapolis Recorder:

. . . so long as wild men will be permitted to roam at will with ropes, shot and torch, so long will a cloud of national shame hang over the government. It is known that almost all of the lynched are members of the colored race, and in many instances the color of their skin is their only crime. It is also known that in the section of the country where almost all this barbarous and un-Christian practice is loved and cherished the colored people have no voice at the courts of mercy.

In knowing these stories, we can begin the process of healing. It will neither be swift, nor easy, but it is vital for our democracy. We owe it to the names engraved on each corten steel beam in Montgomery, Alabama, of at least 18 are from the Hoosier state.

Thanks for watching. Please click “like” in you enjoyed this video and make sure to subscribe to keep updated on all new videos. To learn more about Flossie Bailey, check out Nicole Poletika’s article from the Indiana History Blog. Learn about other stories of lynching at Chronicling America and Hoosier State Chronicles. The links are in the description. Finally, have you visited the National Memorial for Peace and Justice? Were you aware of lynchings in Indiana before? What do you think we can do today to advance peace and justice? Leave your answers in the comments below. We want to hear from YOU.

Articles from Chronicling America and Hoosier State Chronicles