Almost exactly 111 years ago, in January and February 1904, readers of the Indianapolis Journal and Sullivan’s Union and Democrat encountered this news.

An “eccentric” Sullivan County resident — the Hermit of the Wabash, journalists were calling him — had just survived a winter flood on the river. A late-January thaw sent at least two feet of ice water into the hut he called home. Unable to get to higher ground, the 74-year-old recluse passed two frigid days and nights without heat or food, cooped up under his roof, waiting for the flood to recede. The man was “greatly prostrated by this terrible experience.” Doctors were treating him for exposure.

Many readers around Sullivan and Merom knew this “hermit,” or at least of him. He read and wrote poetry, looked like Tolstoy or John Muir, and lived in a remote rustic shack, like his near-contemporary Henry David Thoreau.

Ruth Eno Durham, a Graysville historian of half a century ago, who probably met the hermit when she was a girl, wrote in 1959: “He was a naturalist, a philosopher, a man of culture and refinement living the life of a mussel man, fisherman and outdoorsman.”

Sullivan County historian Tom Frew even believes the “Hermit of the Wabash” is at the center of one of the great photographic mysteries of the Civil War era. Frew may be right. While identifying the “quiet philosopher” as the mystery man of 1859 is uncertain, he was undoubtedly nearby when that iconic image was made, during one of the meteoric events that led up to the war.

How did this ex-Confederate, nature lover, and happy recluse get to a remote corner of the Hoosier State?

Back in 1885, as Ruth Durham recalled, a “small boat with a lone occupant” came up the Wabash and landed at Merom, next to some men out fishing the river for mussels. Midwestern rivers then were full of these creatures. The meat provided food, while their glistening shells were shipped to thriving button factories in Cincinnati. Several small Indiana river towns prospered in the button industry in those days. Mussel harvesting was not banned until 1991.

The lone stranger announced himself. He was “Captain Roland Smythe,” a pseudonym. “He went up the ferry road,” Durham writes, “got some supplies and rowed on up the river.” Easing into the mouth of Turman’s Creek where it flows into the Wabash, the strange boatman met Ruth’s father-in-law, Dr. John L. Durham, “who was standing there and owned the land.”

Smythe and the doctor became friends right away. Durham let him build a two-room hut, christened “Solitude,” on the property he owned with his wife, Mary Mann Durham. The mysterious newcomer lived there for more than twenty years. “Solitude” sat on a high bank of the Wabash, a spot less prone to flooding — though in 1904, his luck ran out.

George Bicknell, a minor Hoosier poet from Sullivan, went out to meet the hermit at Turman’s Creek one summer. His article in Craftsman magazine (September 1909) describes the visit.

Bicknell and others reported that the fascinating hermit was intensely religious, though (like John Muir) unconventionally so. A graduate of the University of Virginia, Smythe was “able to express his thought brilliantly [and] has often been urged to write for publication, but he always refuses . . . [He] says always he prefers to live his song rather than sing it.”

Like Thoreau, who “traveled a great deal in Concord,” discovering the multitude of life in a small place, Captain Smythe was not always solitary. “Hundreds of people visit him every year,” Bicknell wrote. “Many unusual and curious questions are asked him . . . His understanding and knowledge of the classics is unusual. He probably has not seen a set of Shakespeare in forty years, yet there are whole passages from any of the plays which he can give you word for word . . . “

Hundreds of visitors came to “Solitude” to see how he lived the so-called “simple” life. Eventually, the hermit’s own children came. Around 1900, a daughter who lived back East “followed his trail” out to Indiana. Two years after the flood, a 1906 article in the Hutsonville Herald claims:

this daughter, a member of the wealthy inner social circles of New York, found him cooking a meal on his broken-down stove. There was a pathetic scene. She sat on the river banks pleading his return to ‘civilization’ . . . It was then he declared that the ‘wilderness of houses’ and the cramped life held nothing out to him. ‘I will stay near to nature and live with her,’ he declared.

The true identity of “Captain Roland Smythe” was probably not known to anyone in Sullivan County then. He was born Robert Alexander Caskie in Richmond, Virginia, in 1830. The Hutsonville Herald writer mistakenly thought he came from an aristocratic Old Virginia family, “blue bloods . . . whose forefathers dwelt in mansions on the James.” Caskie’s father, in fact, was an immigrant from Ayrshire, Scotland.

The future hermit was educated at the University of Virginia, one of the greatest southern universities during the period. On December 20, 1859, he married Amanda Gregory, daughter of a former Virginia governor, John Munford Gregory. When the Civil War broke out, Caskie went on to serve as captain of Caskie’s Rangers, a mounted company in the 10th Virginia Cavalry. He fought in many of the major battles of the war, including the last one, at Appomattox, where he was mustered out, having been promoted to colonel in February 1865.

A broken man at war’s end, Robert Caskie went back to his family’s tobacco business. But with the South in ruins, he eventually took his family west, becoming one of the biggest tobacco merchants in Missouri. In the late 1870s, the Caskie family was living at Rocheport, on the Missouri River, just west of Columbia.

Bankrupted by a lawsuit back in Virginia, around 1884 the desperate tobacco dealer abandoned his family. On the verge of being driven into poverty, he seems to have chosen it on his own terms. It was then that he rowed up the Wabash, seeking (it seems) a remote place to hide from creditors and his family alike. Durham thought he was too proud to live on his wife’s money.

Robert Caskie had become “Captain Roland Smythe.”

Whatever else his visitors knew about his life, it was an event he had witnessed back in 1859, just a few weeks before he married the daughter of the ex-governor of Virginia, that really stuck in their minds.

In October of that year, the radical abolitionist John Brown tried to spark and arm a massive slave revolt by raiding the Federal armory at Harpers Ferry on the Potomac. Brown’s raid failed catastrophically, inducing anxiety among Virginians. Considered the greatest “terrorist” of his time, the much-hated Brown was scheduled to be hanged on December 2.

To increase security while Brown languished in a Charlestown prison a few miles from Harpers Ferry, Virginia governor Henry Wise had organized several militia companies. One formed in Richmond was known as the “Richmond Greys.” Robert Alexander Caskie appears in their roll book and, as he told the poet George Bicknell, he went to Charlestown that November.

Stopping at the jail where John Brown was being held, Caskie managed to strike up a conversation and friendship with the condemned abolitionist. The 29-year-old Caskie even got permission from Brown’s guard to bring him the newspapers. He also claims that it was he who finally convinced Brown to send a telegram to Philadelphia for his wife.

On December 2, 1859, Caskie watched as Brown stepped up to the gallows, his body on the way to “mouldering in the grave,” as the famous enemy of slavery was memorialized in a Civil War song. Many years later, Caskie described what he saw to George Bicknell:

The wagon was driven through the line and up close to the gallows. John Brown jumped to the ground and skipped up the steps to the platform as though he were a mere boy.

The gallows was unusually high, giving a view of a landscape unsurpassed for its beauty and grandeur. The sun shone with all its brightness, the grass was still green.

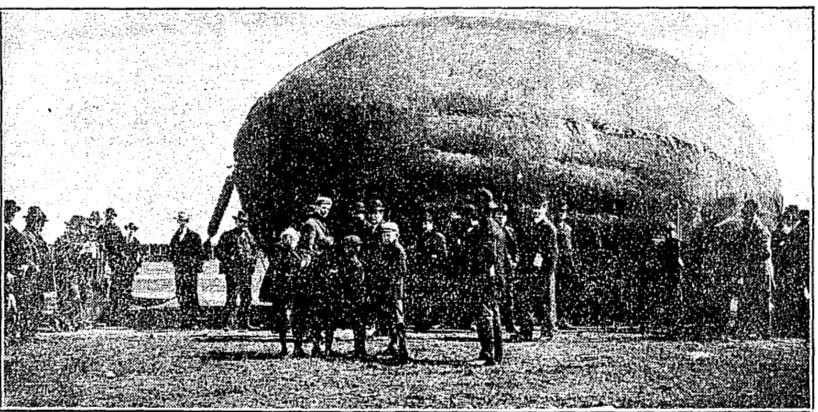

It is possible, even likely, that Robert A. Caskie appears in two of the most famous images taken at the time of that event. These are two ambrotypes — a “relative” of the daguerreotype — that languished in obscurity until 1911. Historians generally agree they depict the Richmond Greys and were made in Charlestown just before Brown’s execution. The first one, known as “RG #1,” has become one of the iconic images of the Civil War era. (It was featured in Ken Burns’ famous documentary and book.)

Robert A. Caskie, the “Hermit of the Wabash,” might be the man with the mustache and goatee standing in the middle of “RG#1.” Comparing this to the few other images we have of him, including in old age, the faces are similar.

“RG #1” is a famously contentious image. At least three of the men depicted here — including the one now thought to be Caskie — have been “forensically” examined and identified as John Wilkes Booth. The other two men stand in the left corner.

Lincoln’s assassin, in fact, saw John Brown’s hanging. It is thought that Booth was leaving a theater in Richmond when the Richmond Greys marched by, and the 21-year-old Shakespearean actor bought a uniform from them. Booth definitely witnessed Brown’s last moments.

Booth, too, has a surprising connection to Indiana. His father, the English actor Junius Brutus Booth, fell ill and died on a riverboat on the Ohio River across from southern Indiana in 1852, while en route from New Orleans to Cincinnati, probably after drinking river water.

Under pressure from his children, and “after he became too old to stand the rigors of the river,” Robert Caskie finally left the Wabash Valley around 1910.

In June 1931, a writer for the Sullivan Union remembered that after he left “Solitude,” “Captain Smythe” lived with Ed Salee’s family in Sullivan, then moved off to Indianapolis with the Salee family. One of Caskie’s sons eventually came out to Indianapolis from New York or Philadelphia. “This was the last that was ever heard of the old hermit of the Wabash by the Salees or anybody in this community.”

But the hermit’s adventure was not done. In 1922, aged 90, he applied for a passport and traveled to France and Switzerland, where he lived with a daughter.

Aged 98, Col. Robert Caskie died of heatstroke in Philadelphia in August 1928 and was buried there. In later years, “The Hermit” was reburied at Richmond’s historic Hollywood Cemetery, near many of the honored Confederate dead.