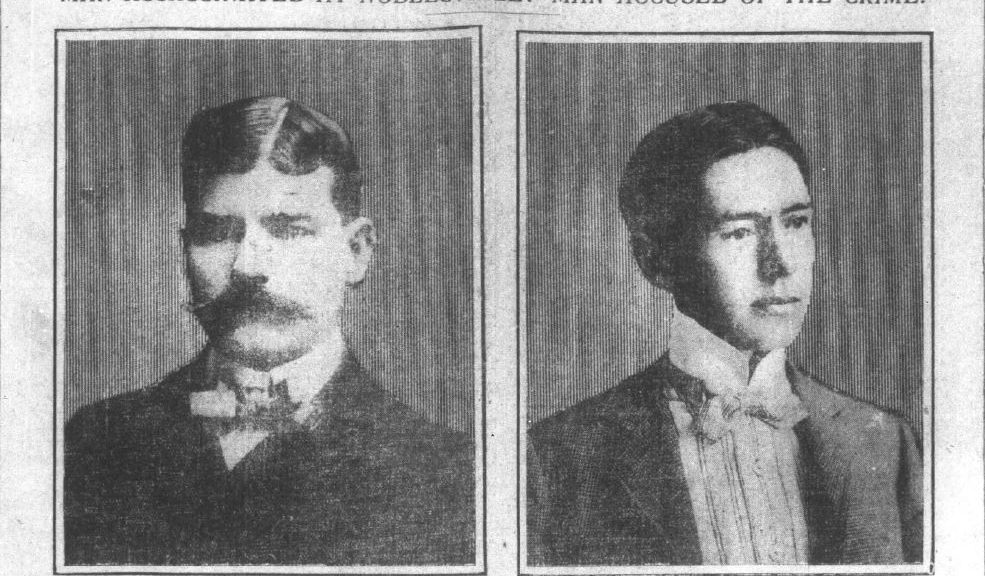

It turns out that James P. Hornaday’s coverage of the Martinique and St. Vincent earthquakes was not the only big story in the Indianapolis News in the summer of 1902. A heavily-covered murder trial also graced the front pages during those months. William Fodrea, a young man with a penchant for engineering, stood accused of the murder of John Seay, an employee of the Noblesville Mining Company. Seay’s mysterious death and Fodrea’s equally mysterious alibi opened up a tale of unrequited love, obsession, and murder that captivated readers of both the News and the Indianapolis Journal. The resulting trial took many twists and turns before the jury’s surprising, unexpected decision. In the end, many walked away from the trial with more questions than answers and the details of that fateful night still remain obscured.

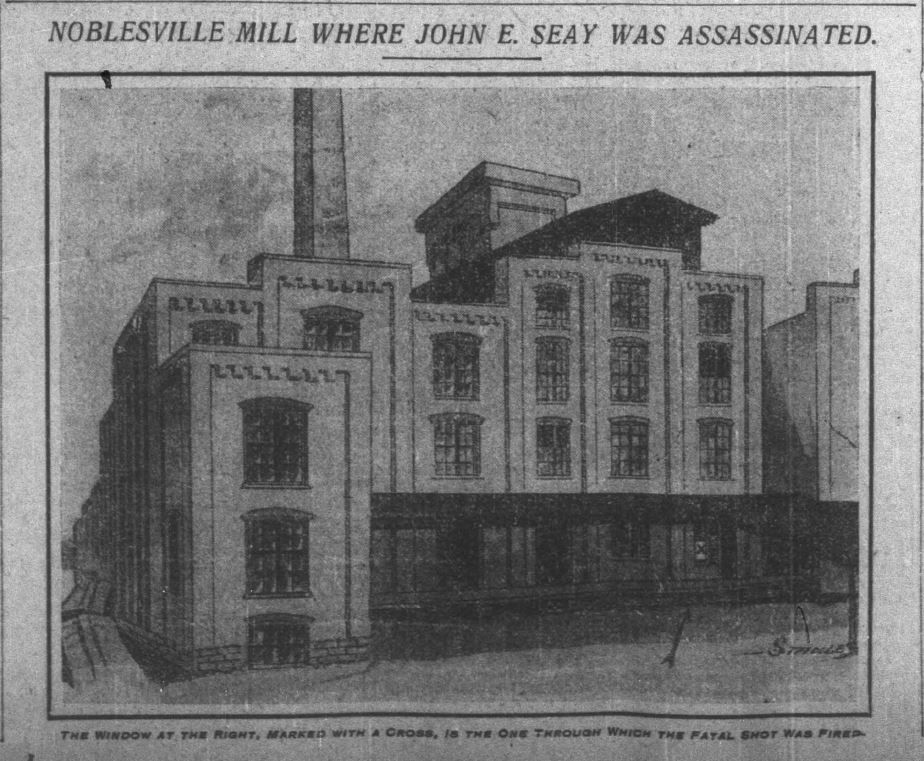

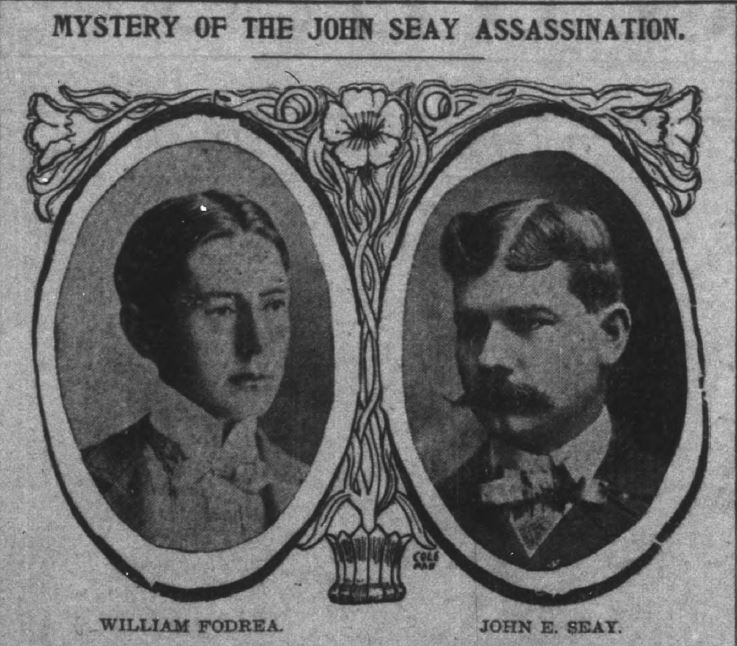

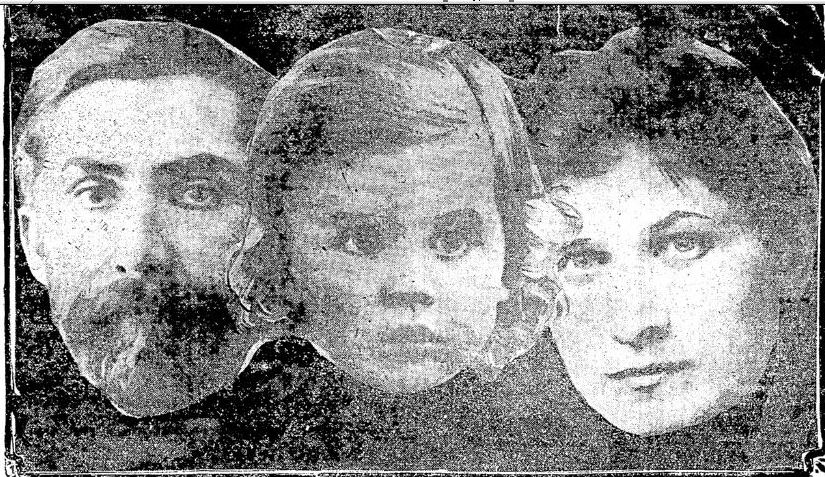

The murder of John Seay occurred on a cold, snowy night in 1901, just three days before Christmas. “About 1 o’clock yesterday morning,” the Indianapolis News reported, “while John E. Seay, in the employ of the Noblesville Milling Company, was resting on a stairway, a load of buckshot, fired by an assassin through a nearby window, entered his neck and head and he fell dead.” Within hours of the murder, attention turned to likely culprit William Fodrea, the twenty-five-year-old son of a former county prosecutor and aspiring engineer. Fodrea’s name rose to the top of officials’ list because he was reportedly obsessed with Seay’s girlfriend, nineteen-year-old Carrie Phillips. “Fodrea was infatuated with the girl and insanely jealous, and, it is said, made threats against Seay,” the News wrote. When Phillips rejected his advances, Fodrea increasingly fixated on her, “lingered” in her neighborhood, and was even “found hiding under the veranda” of her home. When she chose Seay instead, he was said to have lost all composure, resulting in the other suitor’s murder.

Fodrea, “perfectly calm and collected when arrested,” claimed total innocence. Even so, local authorities used a “‘sweat box’ examination,” but it “failed to compel the accused to implicate himself.” For context, a “sweat box” was an often-used torture device in US prisons that isolated the incarcerated in a small room with a tin roof. Due to a lack of ventilation, these small rooms greatly increased in temperature during the day and made prisoners “roast in the grueling heat, enough in some cases to cause death, or little better, madness.” It apparently did neither to Fodrea and he stayed locked up in the Hamilton Country jail while authorities began to sort out the crime.

From the initial investigations and throughout the trial, only circumstantial evidence linked Fodrea to the crime. Fodrea claimed to have never known Seay, and when asked to identify him in a photo, said that, “So far as that man is concerned, I never saw him before.” Despite his claims of innocence, other clues began to trickle in. The first piece of evidence found was a gun barrel, discovered by “school boys under a brush pile on the outskirts of the city.” As for testimonial evidence, Carrie Phillips and her mother both claimed that Fodrea’s obsession bubbled into a frenzy, with him finally declaring that “if he could not go with the young woman no one else could.” Phillip Karr, night manager of the Model Mill, said he saw Fodrea “loafing about the place late one night about a week before the shooting.” While these developments seemed damning on the surface, authorities noted that “these incidents will fall far short of being sufficient to convict him, if there are no new developments in the case.”

Ralph Kane, a veteran prosecutor, replaced J. Frank Beals after he withdrew from the case, citing his wife’s familial relationship to Fodrea. Judge William Neal began the process of establishing a grand jury to investigate the murder in more detail. The Hamilton County Council also convened, “acting on a petition signed by fifty business men,” to appropriate funds towards “a reward for the arrest and conviction of the assassin of John E. Seay.” One indication that the prosecution might have a case against Fodrea was that Seay did not appear to have any enemies in his former home of Richmond, Virginia. The grand jury first met on February 18, 1902. The Journal noted that, “Judge Neal, in his instructions to the jury, said no indictment could be returned against Fodrea unless there was a probability of guilt.” The case still hinged on circumstantial evidence. As such, Judge Neal further “instructed the jury to devote all of its time to the inquiry.”

By March of 1902, the investigators were still continuing their search, but were confident that they had “unearthed much new evidence against him.” In the meantime, the Hamilton County Council “appropriated $600 for the defense of William Fodrea” and “$1,000 for the prosecution of the same cause.” By April, Hamilton County’s Circuit Court teased a trial date, likely sometime in the summer term.

The trial for the murder of John E. Seay began on June 9, 1902, at the Hamilton County Circuit Court. Billy Blodgett, a titan of turn-of-the-century investigative journalism, covered the proceedings for the Indianapolis News. The prosecution argued that William Fodrea shot Seay at close range while he was resting on a step. The alleged round from Fodrea’s shotgun “struck Seay in the neck and head, tearing a ghastly wound in his throat, and several of the grains of shot penetrating his brain.” Despite the cursory investigations indicated “no trace of the murderer,” a police officer had heard that Fodrea made threats against Seay. Fodrea, maintaining his innocence, “said he had gone downtown between 7 and 8 o’clock that evening, and visited different places, returning home about 10 o’clock. Being unable to sleep, he went back down-town an hour later, and for some time sat on the steps on the north and west sides of the court house.” He returned home around 2am. Due to the immense cold that wracked Noblesville that December night, the police were not sold on Fodrea’s story, especially his lounging on the courthouse steps. He was arrested soon thereafter.

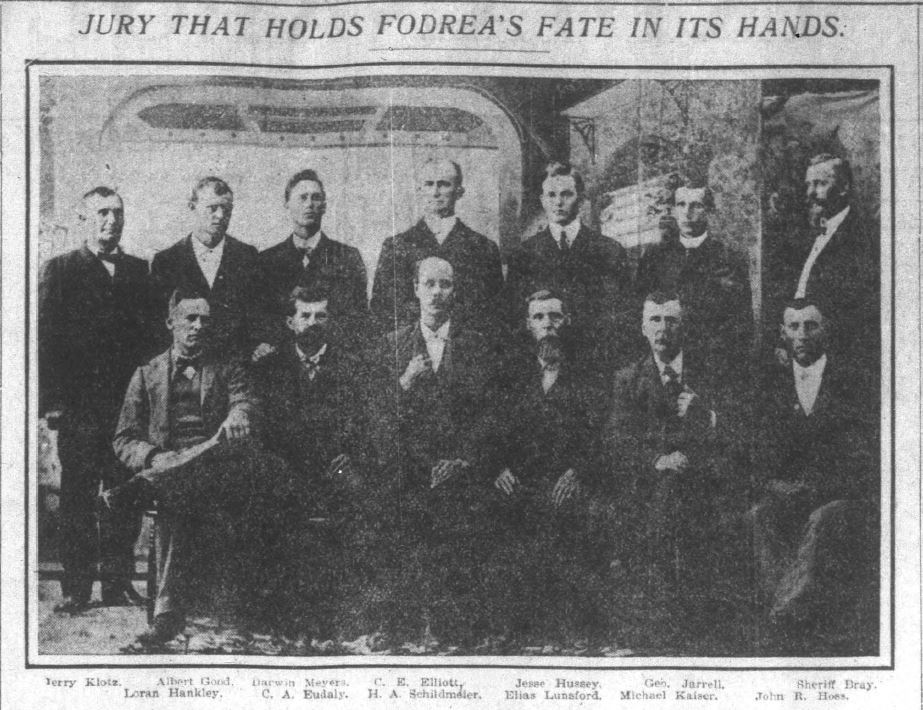

The prosecution hung the success of their case on the testimony of Carrie Phillips. They again remarked of his odd behavior directed towards Miss Phillips—the passing her by home every day, hiding under her veranda, and his intense jealousy of Seay’s apparent courtship of Phillips. Her mother recalled that Fodrea called on the young woman shortly before the murder, asking for her whereabouts and the full name of her new suitor. Fodrea “said he would get even before long,” according to the State. These circumstantial accounts, while wholly based on the imperfect testimony of other people, painted a grim picture of the young man. The murder also highlighted a growing problem within Hamilton County. As Blodgett wrote in his first article for the News, “The killing of Seay was the third crime committed in Hamilton County within a short time, and consequently there was great indignation, not only at the murder, but because of what is termed ‘the epidemic of crime’.” The first day also focused on the selection of a jury, of which only two of twelve men would be over forty. This measure was taken to accommodate Fodrea, who was only 25 at the time and to ensure a fair trial. Leota Fodrea, William’s sister and a “prominent schoolteacher of the county,” showed “her devotion to her brother by her consistent presence by his side.”

The next day, the prosecution laid out its case in greater detail. Ralph Kane, lead prosecutor for the State, reiterated the problematic behavior of Fodrea and his supposed threats to Seay and Carrie Phillips. He argued that witnesses claimed to have seen Fodrea “lurking around the mill late at night and was seen standing at another time on the spot at the mill where the murderer stood” as well as “peering into the mill when Seay was there.” He also “caused a sensation when he declared that the State will show that the night of the murder, William Fodrea was seen within two squares of the mill with a shotgun in his hand.” These conclusions were based on the testimony of twenty-five witnesses, one of which was Frank Bond, a co-worker with Seay at the mill. He discovered the body as well as “12-gauge shotgun wads near it.” Bond then called Dr. Fred A. Tucker, another witness, who examined the body and concluded that Seay died instantly. Head miller Daniel H. McDougall also testified against Fodrea and claimed that he had applied for a job at the mill multiple times and even visited the grounds on three separate occasions.

The second day also provided the jury with details about the lives of both Fodrea and Seay. Fodrea, in his mid-twenties, called Hamilton County his home for most of his life. As the News wrote, “he has always been modest and unassuming and did not have a large circle of friends.” His life had taken for the worse after his laundry business went belly up as a result of a bad business partner, which prompted the young man to say, “It seems as if everyone that has anything to do with me beats me.” Seay, much like his accused assailant, lived a quiet life and kept to himself, likely the result of a speech impediment. He had very few close friends and lived modestly, dying with only a few hundred dollars to his name. What linked these two seemingly innocuous men was their relationship to Carrie Phillips.

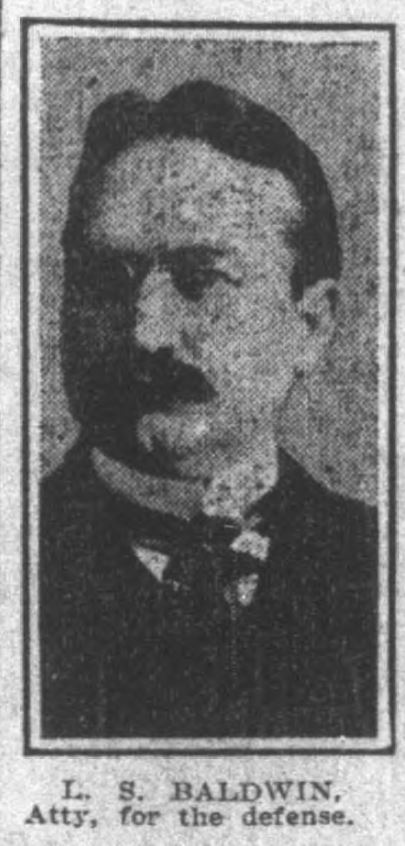

Fodrea’s defense, led by Linnaeus S. Baldwin, sought to poke holes in the prosecution’s case by establishing doubts about the circumstantial evidence. This proved to be a difficult task; a gun barrel was found near the murder scene and further eyewitness testimony suggested that a “man wearing a long overcoat” had been spotted close to the mill. The defense leaned on character witnesses for Fodrea, specifically his family.

Fodrea’s mother and father corroborated that their son was at home during the times he described and spoke of his good character. In particular, his mother noted that he was “very fond of machinery and wanted a job at the mill,” which paints his intentions with the mill in a different light. Additionally, the court came to a near stand-still when Fodrea’s sister took the stand. “She told of the dolls he made her,” Billy Blodgett’s wrote in the News, “the mechanical toys he constructed and the engines he built. Everyone in the room realized that the delicate sister was pleading for her brother, and it had effect at the time.” In all, the defense produced nearly 20 character witnesses for Fodrea, who all spoke positively of him and doubted the claims of the prosecution.

Even though many people testified to the goodness of Fodrea’s character, the testimonies of Carrie Phillips and Myrtle Levi described a completely different man. “Miss Phillips said she had known Fodrea for four years, and that during that time she had frequently told Fodrea that she did not want him to come to see her any more, but that he persisted in making calls at different times,” wrote the Journal. Phillips’s mother corroborated her daughter’s impressions of Fodrea and further noted that he threatened her and Seay. The defense pounced on this, arguing that “the State could not prove that Phillips went with other company, unless it also proved that Fodrea knew of it and talked about it.” The court agreed, the testimony was challenged, and Phillips was asked “not to say when she began going with Seay.” Regardless, her testimony displayed a man obsessed and incapable of thinking clearly about his relationships. Conversely, Myrtle Levi’s testimony proved more compelling, because she was the only one who directly connected Fodrea to the crime. As written in the News, “She testified that she knew Fodrea, and that on the night of the murder he and a companion came to her house and tried to enter.” He was accused of holding a shotgun, which two other witnesses claimed they saw on his person when he appeared at Levi’s residence. The defendant, asked by his lawyers not to take the stand to defend himself, calmly watched the proceedings as they developed.

On June 16, 1902, after six days of deliberation, the jury shockingly acquitted William Fodrea of all charges; a unanimous verdict was reached on the fourth ballot. The Journal described the atmosphere of the courtroom:

When the verdict, “We, the jury, find the defendant not guilty,” was read there was a sigh of relief from the crowd. Fodrea was as calm and undisturbed as any person in the room. His mother was the first to clasp his hand. Quietly he took the hand of each juror and thanked him while a smile played over his face. His relatives and friends then engaged in a love feast that lasted some time. His devoted sister Leota was not present when the verdict was returned, but after met and embraced him and escorted him to the home from which he had been absent for six months.

Some last-minute developments likely changed the direction of the jury. Thomas Levi, Myrtle Levi’s father, told the court that she did not originally identify Fodrea as one of the men who visited her home. While this important detail likely persuaded the jury, Levi’s personal life may have influenced them as well. As Hamilton County Historian David Heighway pointed out, Levi was a well-known prostitute in the community whose lifestyle might have weighed heavily on their verdict. Heighway’s evidence about her lifestyle comes from the Hamilton County Ledger.

This explanation seems incomplete, in some respects. First, the changing nature of her testimony could have had a stronger impact on the jury’s decision. Second, some of the jury may not have taken her lifestyle into consideration or may have not even known about it. Third, her profession should not have had any bearing on whether her testimony was true or not. The last of these hypotheses is sadly anachronistic; at the turn of the century, Victorian values were still in full swing and it is less than likely that the jury, if they had known about Levi, would have ignored it. Biases are an inherent part of everyone’s experiences, so the jury may have been biased against her from the start. Heighway’s explanation only answers part of this puzzle.

Alongside the knowledge of Levi’s lifestyle and changing testimony, it should be noted that Fodrea was accused of stalking, intimidation, threats, and eventually murder. It is not absurd to suggest that he could have killed Seay as a tragic conclusion to a failed courtship. Yet, as his defense pointed out, Fodrea was only connected to this crime via the woman his alleged victim was interested in. A full murder weapon was never found, eyewitnesses only described a gentleman in an overcoat at the mill, and the only witness who directly connected him to the crime had changed her story before it came to trial. There was enough doubt to acquit Fodrea, but the newspaper accounts of the trial acknowledge that Fodrea’s acquittal came from a weak prosecution, not a strong defense.

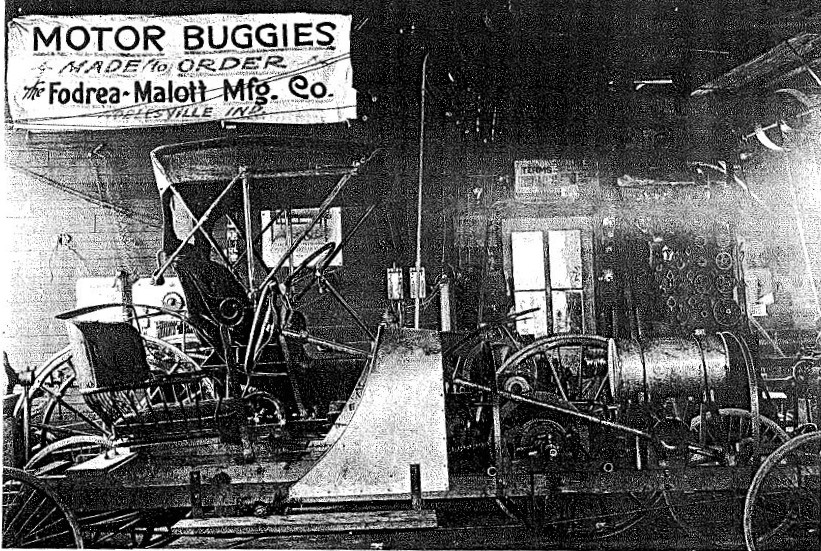

William Fodrea eventually picked up the pieces of his life, but in the most surprising way imaginable. Between 1908 and 1909, he co-founded the Fodrea-Malott Manufacturing Company, where he used his improved transmission design to build a better type of automobile. They developed only one vehicle during their lifetime, the “Beetle Flyer,” which was built by a staff of 8 (including Fodrea). When his partner, Charles Malott, suffered an auto accident in 1909 that destroyed much-needed supplies, the company folded. Malott moved to California and Fodrea moved to Arkansas, “to work on mechanical devices.” To this day, Fodrea-Malott remains the only known automobile company from Hamilton County. Fodrea died around 1945, according to Social Security and Census records.

The death of John Seay and the murder trial of William Fodrea captivated the citizens of Hamilton County and both of Indianapolis’s major newspapers. It displayed all the classic elements of a pulp-crime novel: unrequited love, intrigue, obsession, and murder, hence its extensive coverage by the News and the Journal. Fodrea’s acquittal put to rest, at least for the newspapers, whether or not he actually committed the horrendous deed, but his subsequent move to Arkansas suggests that it continued to haunt him. We may never know what exactly happened on that brisk, December night, but its effects left a deep influence on the community for years after.

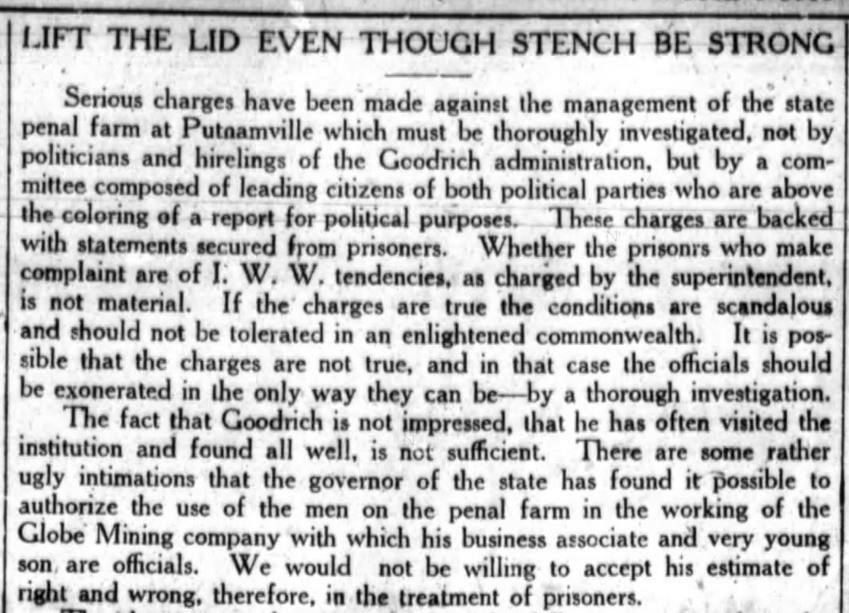

Muncie Post Democrat, August 4, 1922.

Muncie Post Democrat, August 4, 1922.

Lake County Times, December 5, 1916.

Lake County Times, December 5, 1916.

(Lake County Times, June 22, 1913. Hoosier State Chronicles recently portrayed Muncie’s

(Lake County Times, June 22, 1913. Hoosier State Chronicles recently portrayed Muncie’s