In the wake of one presidential hopeful’s recent call to ban Muslims from entering the U.S., we thought it appropriate to share a humorous anecdote about Muslim immigrants in Hoosier history. This story also evokes a mostly-forgotten episode that saw Chicago’s great film companies use the Indiana Dunes as a stand-in for Mexico and the Sahara Desert.

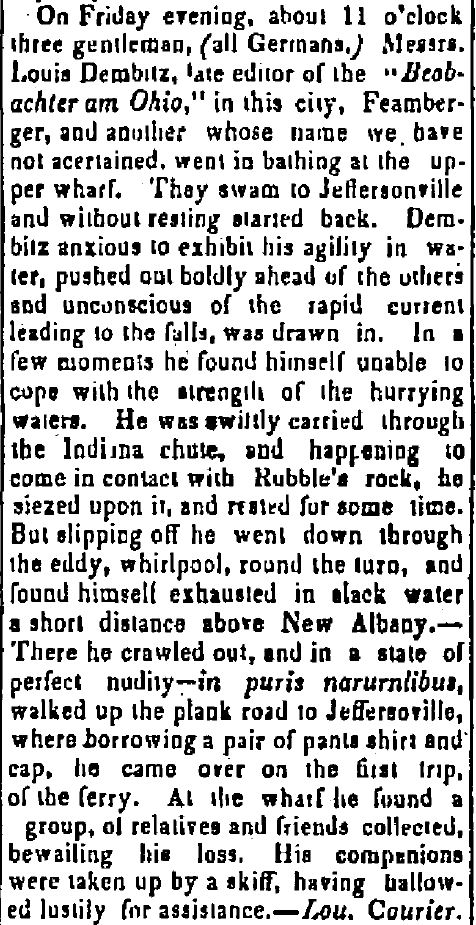

The story came out in both the Gary Daily Tribune and Chicago Record-Tribune. In the summer of 1910, if we can trust the Chicago reporter, some Muslim steel workers shouted excitedly, and maybe even suffered a bit of homesickness when the following scene played out in the streets of the new town of Gary.

(Chicago Record-Tribune, June 14, 1910.)

The Gary Daily Tribune had a different take:

(Gary Daily Tribune, June 13, 1910.)

(Gary Daily Tribune, June 13, 1910.)

In the early days of the silent movie industry, Chicago’s Essanay Studios predominated. Not until the 1920s did the big film producers relocate to Hollywood. Founded in 1907, Essenay’s headquarters were located in Chicago’s Uptown neighborhood. While best known for producing a series of fourteen Charlie Chaplin comedies in 1915 (The Tramp is the most famous), the company also turned out a few American movie “firsts” — including the first American Sherlock Holmes movie (1916) and the first American film version of Charles Dickens’ classic A Christmas Carol (1908). This producer of silent films also scored hits with actor Francis X. Bushman (1883-1966), once hailed as “the handsomest man in the world.” One website calls him the “Brad Pitt of his day.”

(Bushman played the corrupt Roman tribune Messala in director Fred Niblo’s 1925 adaptation of another Middle Eastern tale with Hoosier connections. Ben-Hur, A Tale of the Christ was based on the 1880 novel by Indiana author Lew Wallace, who served as U.S. Minister to Turkey from 1881-1884.)

Chicago’s own sand dunes had mostly been destroyed by 1910, though just a hundred years earlier, they had been the scene of the dramatic beheading of frontier Hoosier soldier and Indian agent William Wells. (Wells, a white captive from Kentucky after whom Wells County was later named, was killed on the beach during the Battle of Fort Dearborn in 1812.) With the growing city looming up on Lake Michigan’s western shore, historic films set in exotic or far-away places had to be filmed across the lake in Indiana. In spite of its proximity to Chicago, swampy northwest Indiana was the last part of the state to be settled and was still largely undeveloped in 1900.

Some of the films Essenay at least partially shot in the area that became Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore include one called Lost in the Desert. That movie seems to have gotten lost itself, but it was apparently part of a series of films by American actor William V. Mong. (Two of his earlier films are entitled Lost in the Jungle and Lost in the Arctic.)

According to an article in The Times of Northwest Indiana, Mong played a “British officer who escapes from Bedouin bandits and wanders aimlessly in the desert until the cavalry rescues him. . .”

In a strange tale of life imitating art, [Mong] became lost in the Dunes after he fell asleep under a tree and the crew left without him. Mong was made up for his role, his clothing in tatters and a leopard skin covering his shoulders.

When he awoke, Mong couldn’t find his way out of the Dunes and was forced to spend the night, suffering from a lack of water and tormented by mosquitoes.

The next morning a trapper from the village of Crisman, making his way through the marshes, was startled to see a ragged, unkempt, half-naked man with long hair and a beard. The strange figure was stumbling through the sand, carrying a club. At times it paused, tried to shout, then moaned inarticulately, and went on his way. The frightened trapper hurried back to Crisman to tell what he had seen. A sheriff’s posse tracked down and rescued the lost man about sunset.

The trapper might have been even more scared if he’d come across Mong in the costume he wore in a 1921 film adaptation of Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court. Mong appeared as the wizard Merlin.

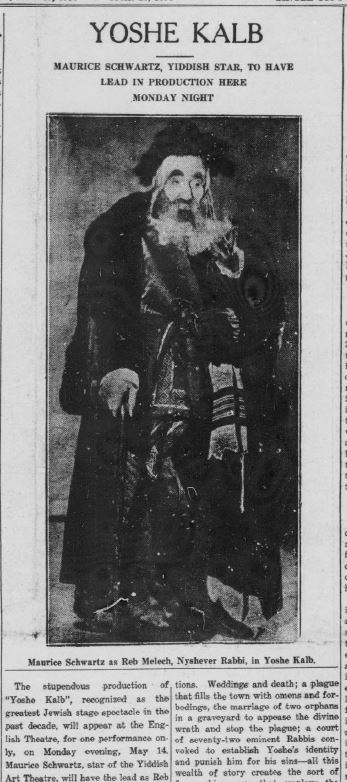

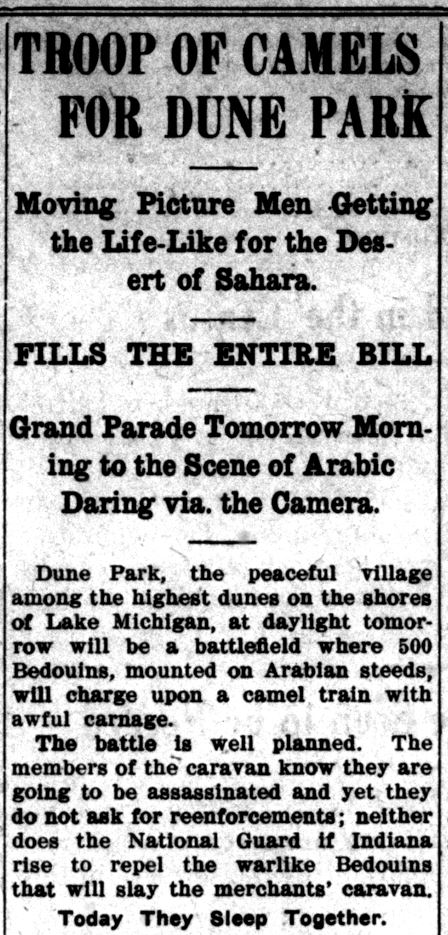

A similar film was made in the Dunes in June 1910, Lost in the Soudan, by the Selig Polyscope Company. This was definitely the film that brought an unusual camel caravan parading through the streets of Gary, Indiana — to great acclaim from a segment of the town’s Muslim steelworkers. Lost in the Soudan starred the great cowboy actor Tom Mix, an early predecessor of John Wayne.

(Filmmakers on the set of Lost in the Soudan, partly filmed in the dunes near Miller Beach, Indiana, in the summer of 1910. Other films made there include The Fall of Montezuma, set during the Spanish Conquest of Mexico, and The Plum Tree, a tale of the Mexican Revolution. The Plum Tree used a regiment of the Illinois National Guard, who impersonated “Revolutionists” and “Federals” in a pitched battle filmed in an Indiana ravine.)

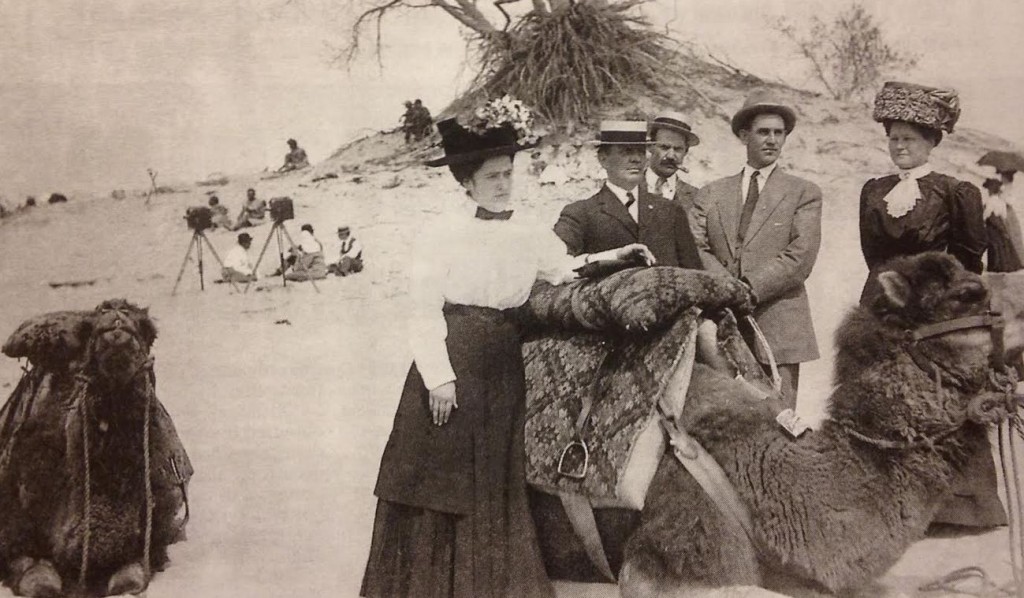

(Ex-president Theodore Roosevelt, left, riding a camel in Egypt or the Sudan, 1910. The man riding the other camel is the English-Austrian soldier, General Rudolf Carl von Slatin, who publicly converted to Islam to win the support of his soldiers.)

We take the Chicago Record-Herald’s statement on faith that the crowd who encountered a film company’s camel caravan in Gary in 1910 were actually Muslim. While some of the first immigrants ever to come over the Atlantic were Muslim — including an estimated 15-30% of the slaves carried here from Africa — the great wave of voluntary Muslim immigration to the U.S. didn’t really begin until just before World War I.

Yet according to a recent history of Islam in America, Bosnian Muslims had settled in Chicago and Gary, Indiana, by 1906, and they may have been the group that shouted “Allah! R-r-r-uum!” at the movie camels on Broadway in Gary. In the 1910s, Bosnians were also working in the copper mines around Butte, Montana, in and played a role in the labor struggles there. In 1906, Bosnian Muslims established a Dzemijetul Hajrije (Benevolent Society) in Chicago to provide mutual aid and help pay for funerals and healthcare. That society soon had a branch in Gary. By 2007, it was estimated that three-quarters of Bosnian Muslims in the U.S. lived in the Chicago-Milwaukee-Gary area.

As the Ottoman Empire collapsed, Muslim immigration picked up after 1918. It’s an interesting fact that one of the first mosques and Muslim cemeteries in the U.S. was founded by Syrian Muslims in Ross, North Dakota, in 1929. (Ross, a town in North Dakota’s remote Badlands, had a population of just 97 in 2010, though those numbers were much higher a hundred years ago.) Another mosque was soon built in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, in 1934. Contrary to popular images, the Midwest has long been one of the cradles of Islam in America, with large numbers of Muslims, for example, settling around the auto factories of Dearborn, Michigan.

Several hundred thousand Middle Eastern Christians, mostly from Syria and Lebanon, also came to the U.S. in those years. (Famous Syrian Americans include former Indiana governor Mitch Daniels, tech wizard Steve Jobs, filmmaker Terrence Malick, and actor F. Murray Abraham, who played composer Antonio Salieri in Miloš Forman’s Amadeus.)

As for camels in the U.S., their history, too, goes back farther than you might think.

In a 1909 article in Popular Science Monthly, Walter Fleming, who taught at Louisiana State University, claimed that the Spanish had brought camels to Cuba for work in mines and that the English had unsuccessfully tried out the use of dromedaries in Virginia in 1701. Fleming wrote that the English also gave camels a go in Jamaica, but the beasts were rendered useless when their feet got infested by Caribbean “chiggers” — a bug well-known to anybody who has hiked around grassy Hoosier fields in the summer.

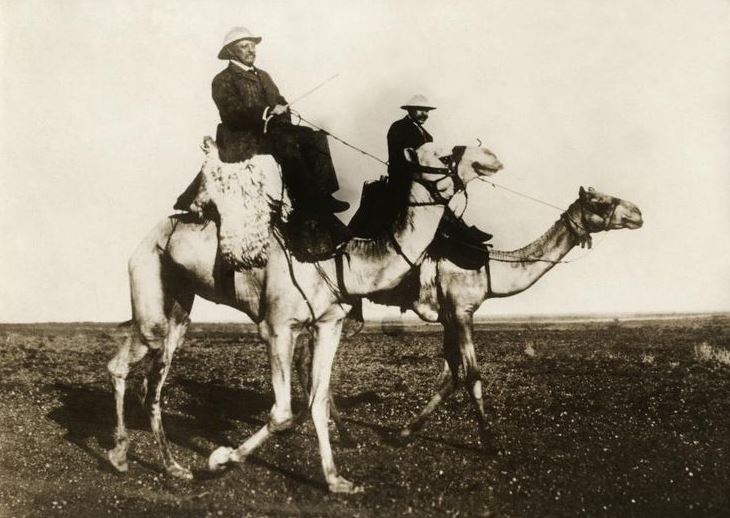

In the wake of the Mexican War, the U.S. Army experimented with a short-lived camel corps in the 1850s. During Franklin Pierce’s administration, the War Department — then headed by Mississippi Senator Jefferson Davis — tried out the practicability of using camels in the arid Southwest, which prior to exploration Americans still thought of as mostly a barren, useless desert. Under the command of U.S. Admiral David Dixon Porter, who had previously served in the Mexican Navy, the navy vessel USS Supply sailed to the Mediterranean and picked up thirty-three camels in North Africa, Turkey, Malta and Greece.

(An awful drawing from the Report of the U.S. Secretary of War, 1857, showing the transport of Middle Eastern camels on a ship bound for Texas.)

(U.S. Secretary of War Jefferson Davis helped start the Camel Corps. The experiment led to the arrival of a group of Muslim caretakers for the camels.)

Jefferson Davis had seen Texas and the Southwest himself as a colonel in the Mexican War. Fleming wrote:

Davis, late colonel of the Mississippi Rifles, made extensive studies in regard to the different breeds of the animal, its habitat, the proper care of it, and its adaptability to the arid plains of Texas, New Mexico and California. . . In March, 1851, he proposed to insert in the army appropriation bill an amendment providing the sum of $30,000 for the purchase of fifty camels, the hire of ten Arabs, and other expenses. In support of his measure he made a speech reviewing the history of the camel as a servant of man and explaining the need for the animals in the west.

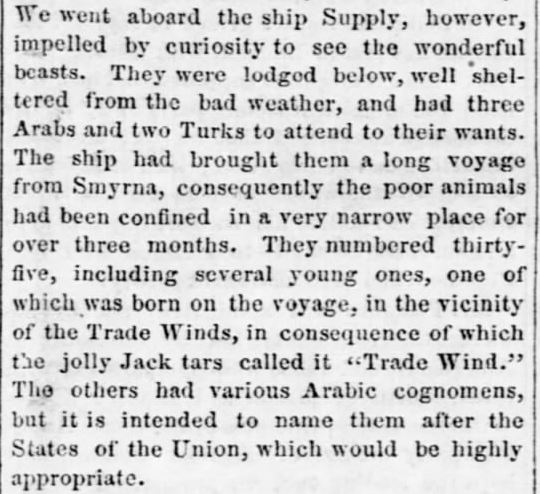

According to a correspondent for the Times-Picayune, “three Arabs and two Turks” landed with the USS Supply in New Orleans in 1856. They traveled with the camels on to Matagorda Bay, Texas, and beyond “to attend to their wants.” Some sources claim these men were actually Greek.

(Raftsman’s Journal, Clearfield, Pennsylvania, July 2, 1856.)

These Middle Eastern dromedaries were used in the Federal government’s war against the Mormons in Utah in the 1850s. While they came to be well-liked by some soldiers, the advent of train transportation made them impractical. The U.S. Army tried using camels to carry the mail between New Mexico Territory and California during the Civil War, though the camels were based primarily out of Camp Verde in the Texas Hill Country.

Lincoln’s war secretary Edwin Stanton ordered the beasts to be auctioned off in September 1863, yet sixty-six of them were still in army possession at war’s end. A few had fallen into the hands of Confederates during a raid on Camp Verde. One camel was said to have been at Vicksburg, Mississippi — in Jeff Davis’ home state — when that town was under siege in 1863.

Walter Fleming also reports that in the 1870s, miners were using some of the ex-army camels to transport salt and cord-wood between California and Nevada silver mines. Others figured into a popular camel race in Sacramento just after the Civil War. Like those who remained in Texas, however, these may have been interbred with commercially-imported animals brought in at a later date by speculators in San Francisco who thought the animals would prove popular in mining, logging, and perhaps even agriculture. By 1910, however, the only industries that found camels especially useful were the Ringling Brothers Circus and Chicago’s film industry.

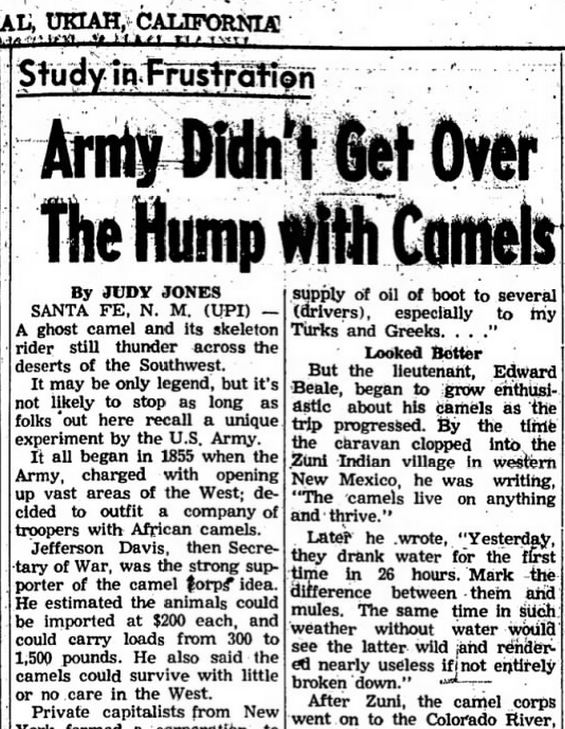

(Ukiah Daily Journal, Ukiah, California, May 9, 1968.)

Most of the beasts brought over from the Mediterranean aboard the USS Supply — or their descendants — had apparently vanished by the early 1890s, when the last of them was reported to have been seen in Arizona. That one might have been shot. In fact, strange, scary stories had begun to circulate about the creatures.

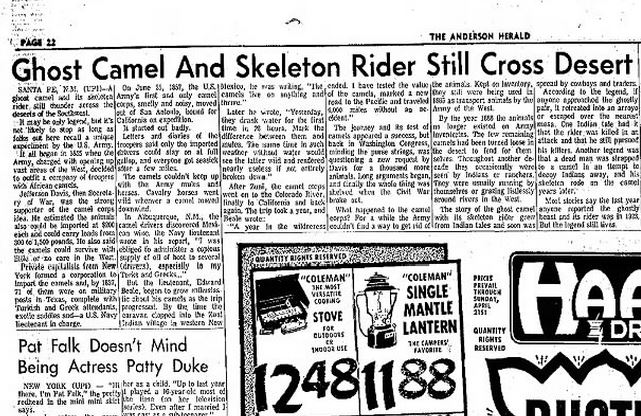

By 1890, “ghost camels” had entered the folklore of the desert Southwest. At least one of these tales about the feral descendants of Jefferson Davis’ Army Camel Corps followed an old trajectory of Irish and American folklore. The humped creature carried around a headless rider. In another version, the devilish-looking beast carried the full skeleton of a rider who had died atop its back. Still another tale involved a Southwestern camel that was seen eating a bear.

News reports about the survival of these wandering dromedaries, believed to have been the abandoned beasts of the Army Camel Corps, kept on coming in. In April 1934, one alleged survivor who had been taken to the Los Angeles Zoo was crippled by paralysis and had to be put down by zookeepers there. Another siting of a “ghost camel” occurred near the ghost town of Douglas, Texas, in 1941. Newspapers were still syndicating these stories in 1968. Smithsonian Magazine even saw fit to re-tell a bit of the story earlier this year.

(Anderson Herald, Anderson, Indiana, April 18, 1968.)

The legend of the “Red Ghost,” in fact, lives on as an “Arizona oddity.” Likewise, the tomb of Hadji Ali. A Greek-Syrian born in 1828, Hadji Ali converted from Christianity to Islam, performed the Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca, and was living in Algeria working for the French Army when the USS Supply came looking for camels. Hadji Ali joined the U.S. Army service, coming to California as a camel tender in 1857, later becoming an American citizen in Arizona Territory in 1880. He worked as a scout and mule packer for the army and participated in the campaign against Apache chief Geronimo.

Nicknamed “Hi Jolly” by neighbors who couldn’t pronounce his name, Ali prospected for minerals on the edge of the Mojave Desert near the Colorado River until his death at Quartzsite, Arizona, in 1902. Following his death, the fascinating pyramid that marks his grave site — erected by fond locals — became one of the roadside attractions of the Grand Canyon State.

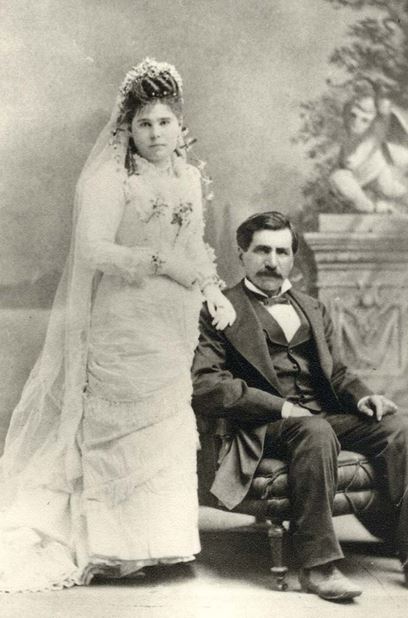

(Hadji Ali, alias “Hi Jolly,” and his bride Gertrudis Serna in Tucson, Arizona, 1880.)

Contact: staylor336 [AT] gmail.com

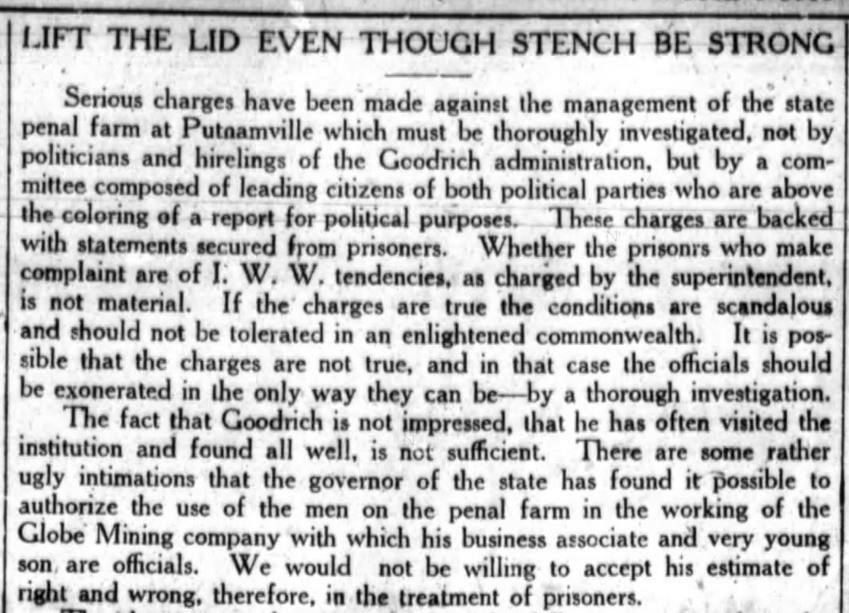

Muncie Post Democrat, August 4, 1922.

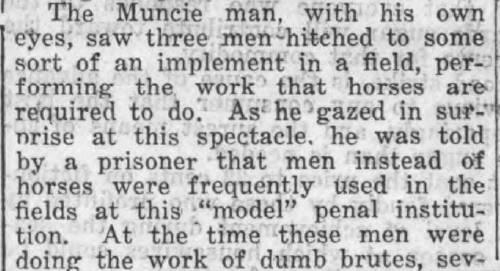

Muncie Post Democrat, August 4, 1922.