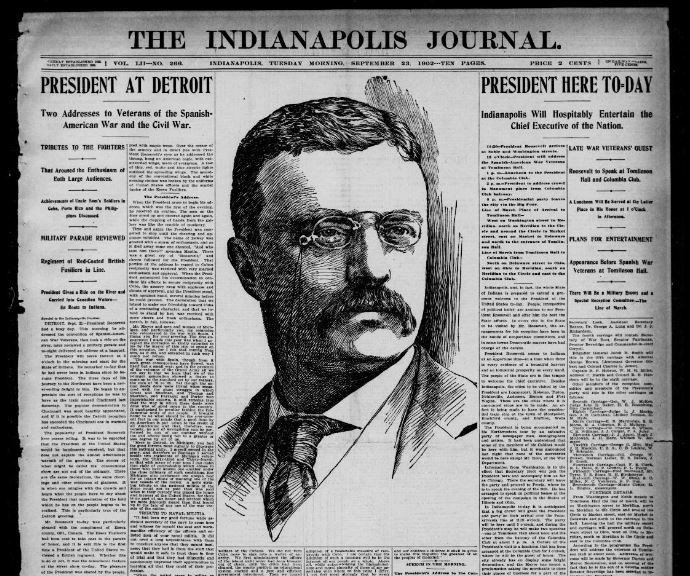

American politics often repeats itself every generation or two. In light of some of the top stories in the media in 2015 — including Pope Francis’ U.S. visit and the first major candidacy of a Socialist for the White House since 1920, that of Vermont’s Bernie Sanders — one fascinating, overlooked tale from the Indiana press is worth retrieving from the archives.

The story starts in Terre Haute, hometown of Eugene V. Debs, the great American labor leader who, as a Socialist, ran for president not once, but five times. A passionate leader of railroad strikes — Terre Haute a century ago was one of the major railroad hubs of the nation — Debs was also a founding member of the Industrial Workers of the World and a vocal opponent of American entry into World War I. When he clashed with President Wilson over the military draft in 1918, he was sent to prison under an espionage act. Debs spent over two years of a ten-year sentence at a federal penitentiary in Atlanta, where he ran for the presidency in 1920 — the only candidate ever to run a campaign from a jail cell.

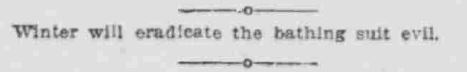

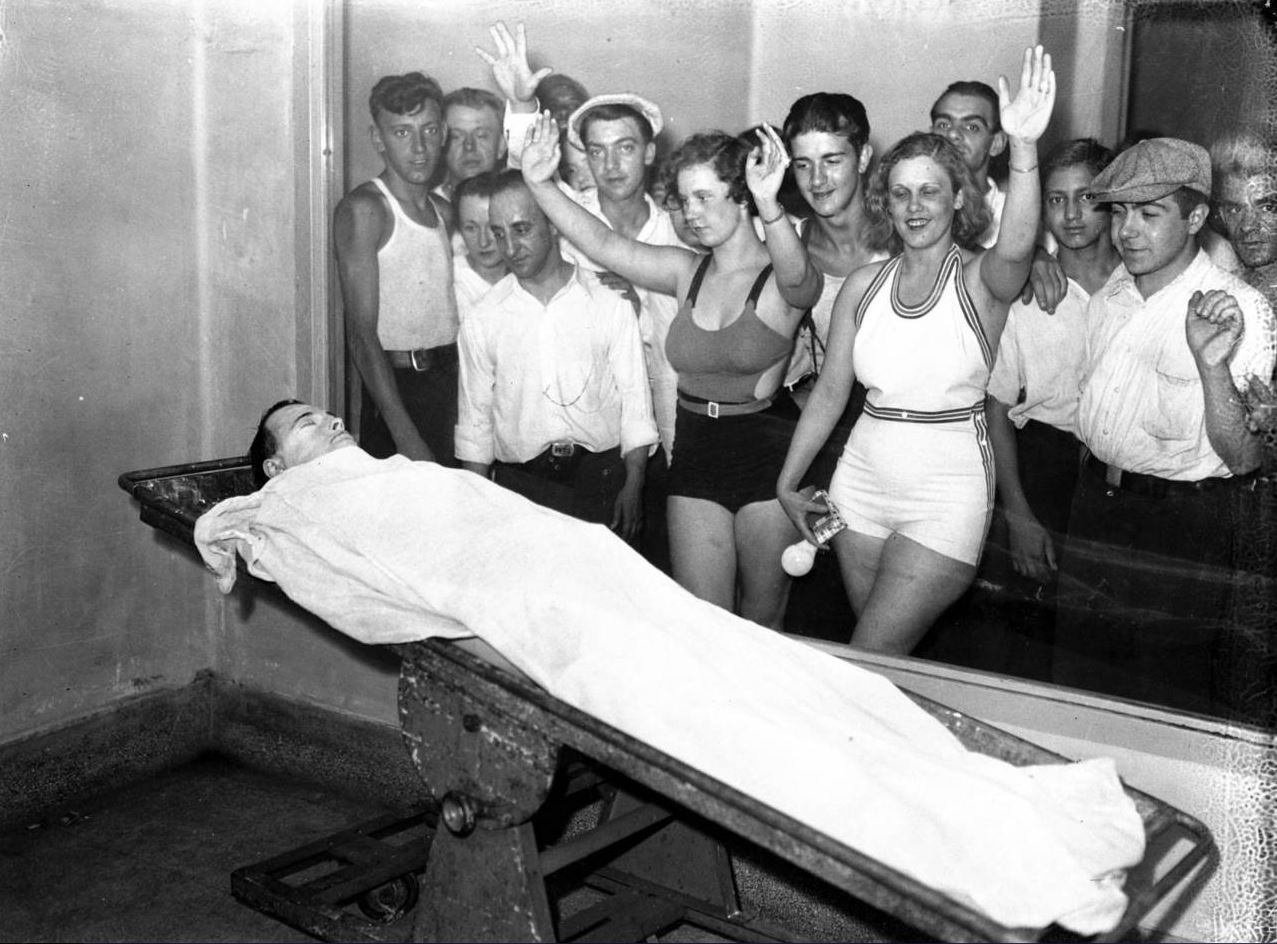

In the summer of 1913, however, Eugene Debs came to the defense of a scorned young woman tossed into Terre Haute’s own city jail. Slandered in the press, she’d been called a “woman in scarlet,” a “modern Magdalene” and a street-walker. Local papers and the American Socialist press jumped on the story of how Debs showed compassion for her, but today the tale is almost unknown.

The alleged prostitute was Helen Hollingsworth Cox (sometimes spelled Hollinsworth in the papers.) Born in Indiana around 1888, she would have been about 25 when her case electrified the city, including its gossips. Helen was the daughter of the Reverend J.H. Hollingsworth, a Methodist minister in Greencastle, Newport, Terre Haute and probably several other Wabash Valley towns.

As Mont Casey, a writer for the Clinton Clintonian, explained, the Reverend Hollingsworth had angered some of his flock by preaching the gospel of Jesus of Nazareth rather than giving “more attention to society and the golf links.” Though Debs was a famous “non-professor” when it came to religion, he and Hollingsworth saw eye-to-eye on issues like poverty, it seems. (In fact, the agnostic Debs, son of French immigrants, had been given the middle name Victor to honor Victor Hugo, author of Les Misérables, the great novel of the poor.) Yet Mont Casey wrote that the Socialist and the Methodist were close friends.

(Greencastle Herald, July 28, 1913.)

(Greencastle Herald, July 28, 1913.)

Some papers had apparently gotten their version of Helen’s “fall from grace” wrong, prompting Casey to explain her “true history.” Set among the debauched wine rooms and saloons of Terre Haute, Casey’s version ventures into the city’s once-flourishing red light district near the Wabash River and the world of the “soiled doves,” a popular euphemism for prostitutes. The scene could have come straight from the urban novels of Terre Haute’s other famous son in those days, Theodore Dreiser, whose Sister Carrie and Jennie Gerhardt were banned for their sexual frankness and honesty.

(Greencastle Herald, July 28, 1913.)

Helen’s minister father may have been denied a pulpit because of his interpretations of the gospel. He also may have been living in poverty and unable to help his daughter. This isn’t clear.

Whatever the truth is, the story went international, perhaps through the efforts of Milwaukee’s Socialist press. (The Socialist mayor of Milwaukee, Emil Seidel, had been Debs’ vice-presidential running mate in 1912.) The tale eventually made it overseas, as far away as New Zealand, in fact, where The Maoriland Worker, published out of Wellington or Christchurch, mentions that Debs was a designated “emergency probation officer” in Terre Haute.

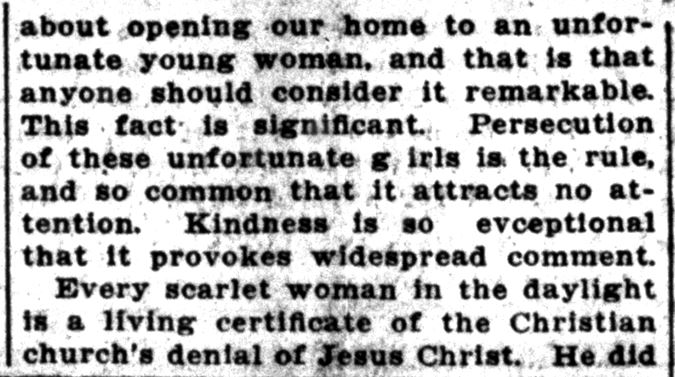

The fires were being stoked. Terre Haute’s well-heeled “Pharisees” — the same type, many pointed out, who had killed “the rebel Jesus,” as Jackson Browne and the Chieftains put it in an Irish Christmas song — apparently weren’t happy about Debs coming to Helen Cox’s defense. When he took the “modern Magdalene” directly into his home (the phrase refers to Jesus’ female disciple, who was also falsely labeled a prostitute in popular memory), Debs declared that his “friends must receive her.”

Son of a formerly Catholic French mother but a freethinker himself, this was a remarkable moment for Debs — who famously said that he would rather entrust himself to a saloon keeper than the average preacher but who was anything but hostile to religion at its best.

(Lake County Times, June 22, 1913. Hoosier State Chronicles recently portrayed Muncie’s Alfaretta Hart, a Catholic reformer and policewoman who would have agreed heartily with Debs’ take on Imitatio Dei.)

(Lake County Times, June 22, 1913. Hoosier State Chronicles recently portrayed Muncie’s Alfaretta Hart, a Catholic reformer and policewoman who would have agreed heartily with Debs’ take on Imitatio Dei.)A clip from the Washington Post added this excerpt from the labor leader’s remarks to the press:

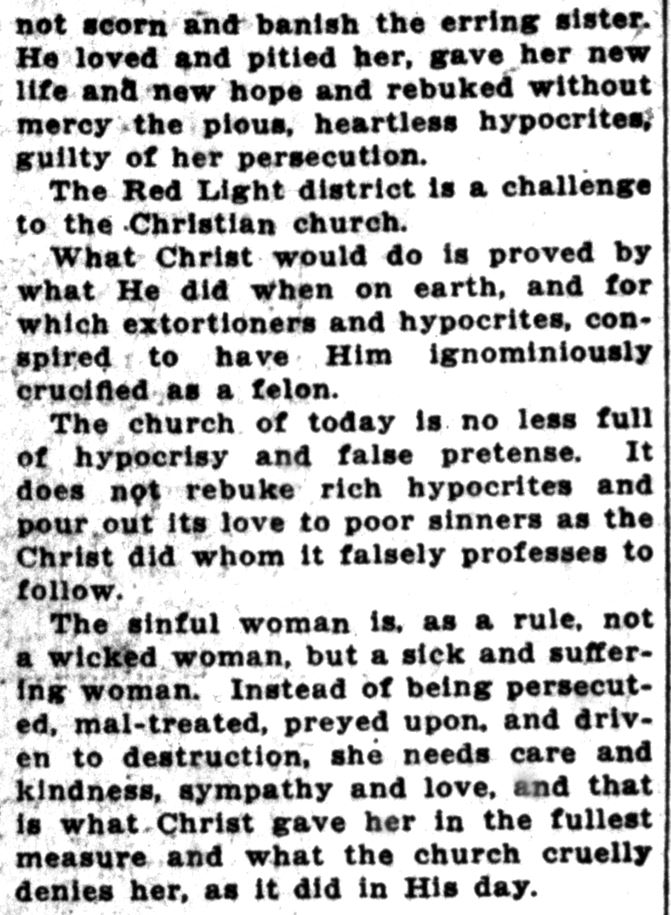

That summer, Debs’ healthy “challenge to the Christianity of Terre Haute” was taken up in the pages of a unique monthly called The Flaming Sword. Published at a religious commune near Fort Myers, Florida, the periodical was the mouthpiece of the Koreshan Unity, an experimental utopian community based partly on Socialist and Christian principles. The celibate group living on the outskirts of the Everglades had been founded by Dr. Cyrus Teed (1839-1908), a former Civil War doctor turned alchemist and messiah who came down to Florida from Chicago in the 1890s. Teed also propounded a curious “Hollow Earth” theory.

Dr. Teed was dead by the time Debs threw down his challenge to the churches, but the Koreshans printed a spirited, sympathetic editorial about it — written by fellow utopian John S. Sargent, a former Civil War soldier and Wabash Valley native.

Helen Hollingsworth apparently got back on her feet thanks to Debs’ help. But she did lose her daughter, Dorothy, born in 1908, who was raised by the wealthy Cox family and Helen’s “reprobate betrayer.” That was Newton Cox, “petted profligate of an aristocratic family,” who died in 1934. During the Great Depression, Dorothy Cox married a banker named Morris Bobrow. She died in New York City in 2000.

Helen’s father, Reverend J.H. Hollingsworth, passed away in 1943. The Methodist pastor had followed his daughter up to Michigan, where in the early 1930’s, she was living in Lansing and Grand Rapids, having married a news broadcaster named King Bard. The 1940 Census shows that the Bards had a 17-year-old “step-daughter” named Joan. The 1930 Census states that Joan was adopted, and that — confusingly — the married couple’s name was Guerrier, at first. It’s not clear why they changed their last name to Bard during the Depression. King’s birth name had been John Clarence Guerrier, the same name on his World War II draft registration card, which lists him as “alias King Bard.”

Eugene V. Debs died in 1926. Helen Bard retired with her husband to Bradenton, Florida, where she appears to have passed away in May 1974, aged 86.