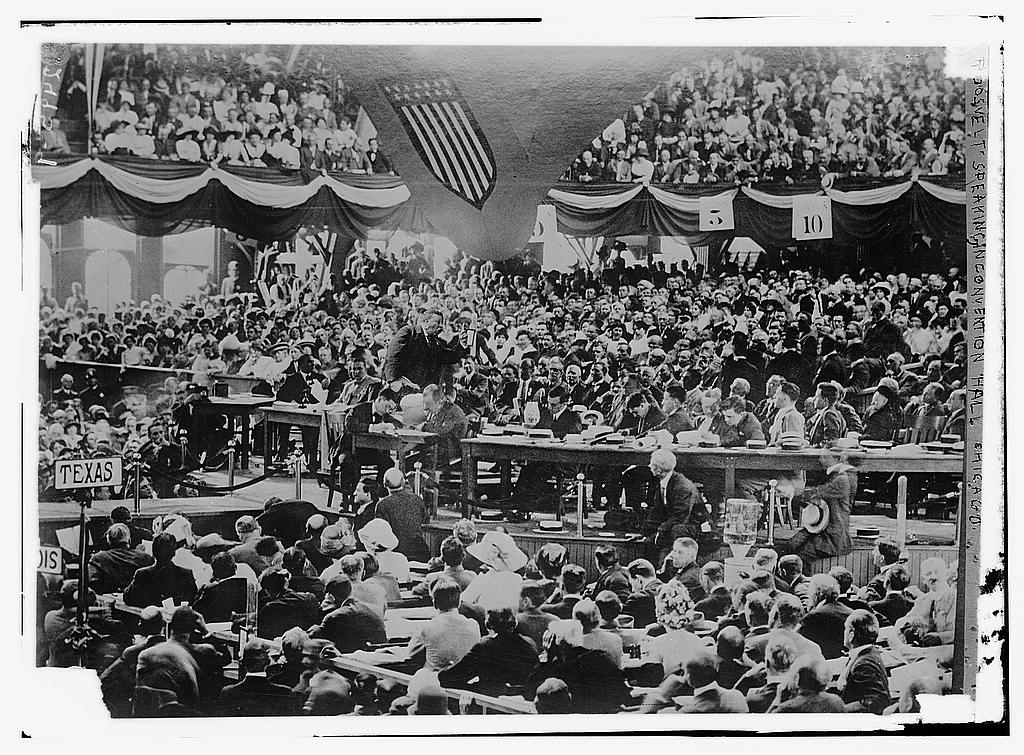

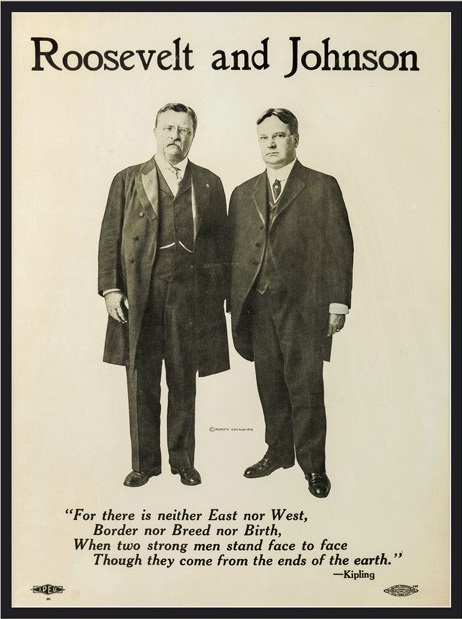

Social media today disseminates news faster than any other time in history. Our contemporary political atmosphere, dominated by the 24/7 news cycle and social media, often churns through stories faster than bills can be drafted and carefully-worded messages honed. One article from Mashable, entitled “The Future of Social Media and Politics”, examined how important social media outlets are to current grassroots campaigns and shaping political influence through direct communication with candidates. Another article, this time from The Atlantic, examines how charisma influences our perceptions of leaders and in what standing we hold them in.

Social media today disseminates news faster than any other time in history. Our contemporary political atmosphere, dominated by the 24/7 news cycle and social media, often churns through stories faster than bills can be drafted and carefully-worded messages honed. One article from Mashable, entitled “The Future of Social Media and Politics”, examined how important social media outlets are to current grassroots campaigns and shaping political influence through direct communication with candidates. Another article, this time from The Atlantic, examines how charisma influences our perceptions of leaders and in what standing we hold them in.

These strategies, while utilizing the most up-to-date technology, are not new. The rise of John F. Kennedy over Richard Nixon was as much a response to his policies as it was his appearance in the first televised debates. The charismatic and good-looking Kennedy swayed many followers away from the established politician Nixon, and helped to shift the public perception on his ability to lead the country.[1] The power of messaging and personality is certainly a powerful tool in getting many leaders elected and crafting their image once in office.

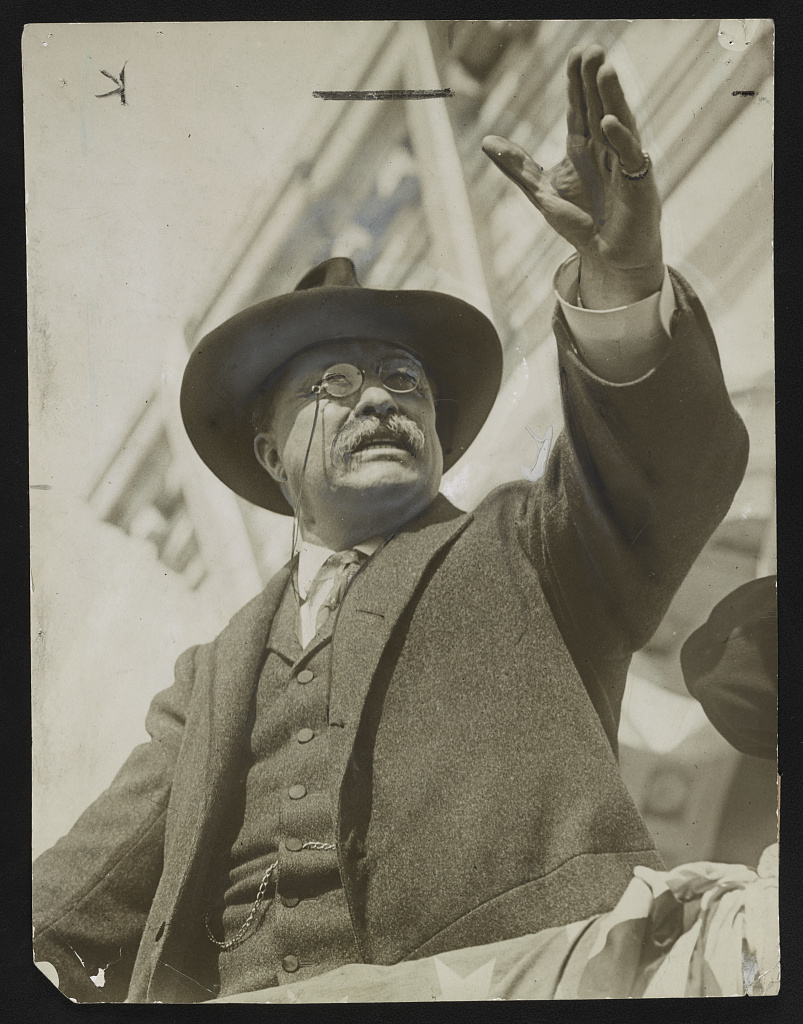

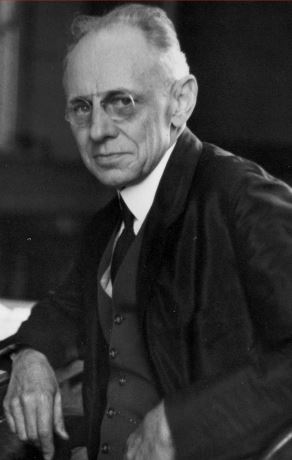

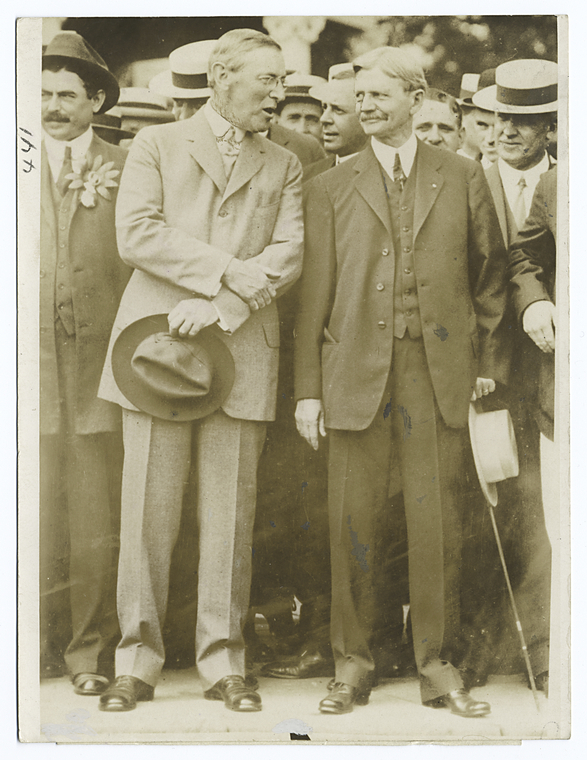

Politics in Indiana during the first part of the 20th century was serious business. It was often dominated by political machines, the Ku Klux Klan, and larger-than-life political figures. However, two-time Republican Indianapolis mayor Samuel Lewis Shank, had no interest in either machine politics or joining the Klan. “Lew,” as he was called, did, however, like the idea of being a larger-than-life politician. Particularly during his first term as mayor, he frequently used the media as an outlet for showy political stunts and self-promotions. While he garnered a reputation as a colorful and outspoken figure, his well-covered tactics were not enough for him to go down in Indiana history as a masterful politician. Indeed, he resigned in late November 1913 with one month left of his mayoral term and was not elected to another political position for nearly a decade before one more stint as mayor.

The popularity of Lew Shank derived from the crafted image of his plainspoken nature, and the fact that he presented himself as the common man. This folksy-geniality endeared himself to the public, and the papers, for years. His career in auctioneering (which continued during both terms as mayor) and time on the stage as a vaudeville performer also provided him the skills to captivate crowds with outrageous stories. The unusual press Shank received during his years in politics, as demonstrated in Hoosier State Chronicles, certainly kept his name in the headlines, for better or worse.

Despite these somewhat unusual headlines, Shank was serious about politics. Shank’s political aspirations began at the age of eighteen. Shank attempted a campaign to become city councilor but was defeated. Undaunted, Shank mounted an ambitious campaign to not only raise his political profile, but also capture the seat of county recorder, wherein he was responsible for maintaining legal documents and records. This campaign included taking out self-promotional advertisements in local papers, partnering with companies to produce objects with his name imprinted on them, (like cigars and chewing gum), and engaging in several publicity stunts. These tactics not only won him the seat of county recorder, but also raised his popularity in local and national papers.

Although a long shot (even for the Republican nomination spot), Shank was able to turn his success as county recorder into a viable campaign for mayor of Indianapolis in 1909. Edging out the favored Republican nominee and then his Democratic opponent, Shank won nine of fifteen wards of Indianapolis with a total of 1,625 votes. [2] Yet he was not above resorting to dishonest tactics to win. Shank recalled to the New-York Tribune in 1912 that he gained an advantage in the mayoral election with the African-American community by stating that his political opponent removed his daughter from an integrated school. He openly admitted lying—his opponent had no daughters at all. [3]

Once arriving in office, Shank had a great deal to prove to the citizens of Indianapolis and within his own party. He relied on theatrics and courted the media. One such effort included the enforcement of saloon laws in Indianapolis, particularly laws which prevented the sale of alcohol on Sundays. Shank, of course, handled the issue with his own particular brand of showmanship. Indeed, he insisted that Indianapolis saloon keepers’ licenses were revoked until they sat through a Sunday church service, among other requirements:

Shank again entered the spotlight with his “High Cost of Living” campaign, a reaction to food pricing throughout the state. Shank, believing the mark-up of food to be excessive, went straight to the suppliers, purchased sundries, and then sold the products to the public at cost on the steps of the State Capitol building. What many could see as a cheap publicity stunt proved to be a boon to Shank’s popularity and actually led to lower prices of groceries in Indianapolis.

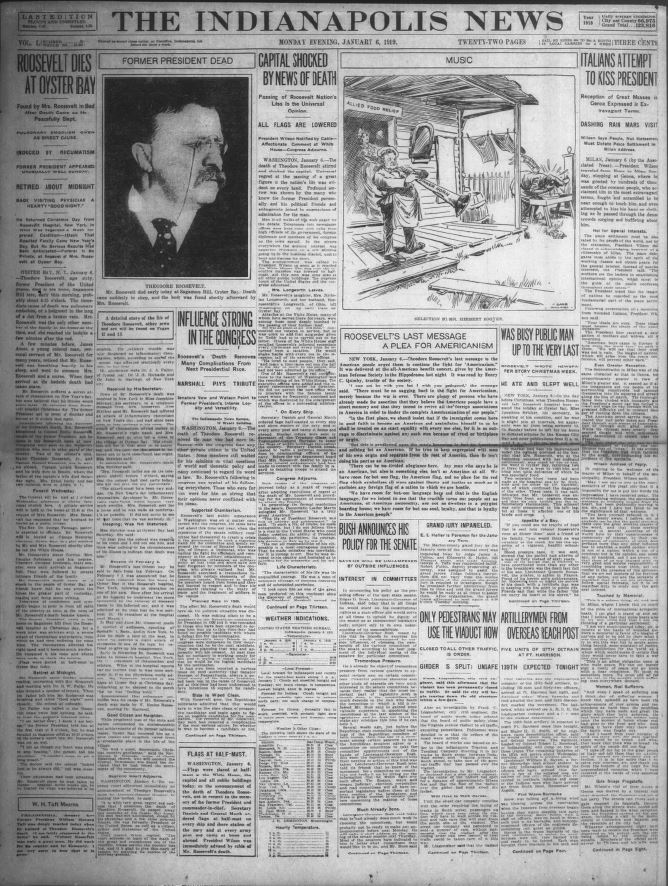

However, his flashier tactics could not resolve the streetcar strikes in November of 1913, which ultimately led to his downfall. The Indianapolis Traction and Terminal employees began a wage and benefit strike. On November 2, the company president brought in strikebreakers, which led to open warfare. A violent clash between strikebreakers and striking workers led to injuries and two deaths. The owners of the line called in strike-breakers to get the lines running again, and requested help from the Indianapolis police department to protect the company men. Due to disagreements between Shank, the police chief, and officers, law enforcement did not provide an adequate response. This did not aid Shank’s standing for many in the city.

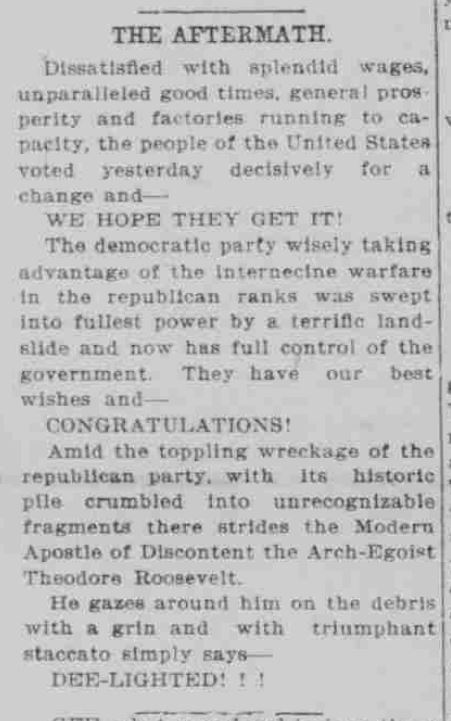

Eventually, after threats of impeachment and another impending strike, Shank resigned his job as mayor, one month short of the end of his term. It is possible this too was a publicity stunt, as he had already signed a contract for, as the Encyclopedia of Indianapolis notes, “the vaudeville circuit with a monologue about his time as mayor.” It would be nearly nine years until Shank would be elected again to public office, and his exit was met with a generally negative response:

During his second stint as mayor of Indianapolis in the early 1920s, he actively opposed the Klan through such methods as banning masked parades and burning crosses. [4] Although easily defeated, he ran in the Republican primary for governor in 1923 against the Klan-backed nominee (and eventual winner), Ed Jackson, in an effort to stem the statewide power of the Klan. Despite his non-traditional career path and aspirations for higher office, Shank’s rise in politics, led by his ability to capture media attention, was an improbable example of both the powers and limits of charismatic politics.

[1] For more information about the Nixon-Kennedy debates, see Time magazine’s article, “How the Nixon-Kennedy Debate Changed the World”

[2] The Indianapolis News, Wednesday Evening edition, November 3, 1909, p. 1.

[3] “Mayor Shank Tells How a Brace of Imaginary Daughters Helped Elect Him”, The New-York Tribune, February 25, 1912, p. 19. Accessed February 2, 2019. https://www.newspapers.com/image/467701598/

[4] “Samuel Lewis (Lew) Shank,” Encyclopedia of Indianapolis, edited by David J. Bodenhamer and Robert G. Barrows, (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994), 880.

The Ogden Standard-Examiner, Ogden, Utah, February 11, 1923.

The Ogden Standard-Examiner, Ogden, Utah, February 11, 1923.

Lake County Times, December 5, 1916.

Lake County Times, December 5, 1916.