Newspapers are an essential historical resource for researchers, journalists, and genealogists by capturing the lives and events of individuals in a particular area throughout the years as well as reporting national news. However, even under the best climate and preservation circumstances, the longevity of newspapers is hindered by the relatively short lifespan of newsprint, a thinner and lower quality of paper. One solution in the past was the use of microfilm or microforms. According to Managing Microforms in the Digital Age from the American Library Association, “microfilm has been used since the 1940s for the long-term storage of newspaper content because the medium preserves file integrity, maintains the proper sequence of the data, and discourages theft.”[i] Libraries and historical organizations have used these tools for years, but even microfilm has limitations. It takes up a great deal of space, is expensive to produce, and often requires on-site access.

Over the past twenty years, institutions have shifted their focus from microfilm to digital formats. To aid this transition, the Library of Congress, with funding by the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH), executed a nationwide newspaper project from 1982 to 2011 called the United States Newspaper Program, which cataloged and collected newspapers nationwide. However, in 2005, the Library of Congress and NEH formed the National Digital Newspaper Program (NDNP) and its digital newspaper database, Chronicling America, which offers free access to digitized historic newspapers from across the country via partnerships with statewide organizations.[ii] Indiana’s largest collection of digitized newspapers are housed within the Indiana State Library’s own database, Hoosier State Chronicles.

As a project, Hoosier State Chronicles focused on digitizing newspapers at the state and local levels- sometimes through the NDNP or institutional partners, but often by partnering with groups endeavoring to save their local papers. The efforts of these smaller organizations have been hindered by the lack of information about how to begin such a process, as well as securing the necessary resources to handle storage, digitization costs, and labor. This blog provides an introduction to the entire process of how newspapers are selected, organized, digitized, and publicly shared through Hoosier State Chronicles. To begin, let us start with the formation of Hoosier State Chronicles and its collection of digitized newspapers.

Indiana’s largest public repository of microfilmed newspapers is managed at the Indiana State Library and contains over 3,000 titles. In 2011, the Indiana State Library, Indiana Historical Bureau, and Indiana Historical Society collaborated on the first grant for Chronicling America, which digitized over 100,000 pages of Indiana newspapers. After the initial two-year grant cycle, the Indiana State Library and Indiana Historical Bureau, (now part of the Indiana State Library,) took over future efforts to digitize Indiana papers, eventually creating the Hoosier State Chronicles website in 2015 and receiving three more NDNP grants for digitizing newspapers. This included collaborations with Indiana colleges and universities to digitize partial collections, as well as partnerships with community organizations to digitize local papers through grants.

Today, Hoosier State Chronicles has a collection of over 950,000 pages and 124,000 issues, ranging from pre-statehood (The Indiana Gazette, 1804) to contemporary newspapers (The Muncie Gazette, 2011). The Indianapolis Recorder contains the longest run in the collection with 96 years of newspapers, but because it was a weekly paper, the whole run only contains around 5,000 issues. The largest number of issues for a single newspaper belongs to the Indianapolis News, with over 12,304 issues over 38 years, though The Daily Banner from Greencastle comes in a close second with 10,649 issues spread over 68 years.

An important element of Hoosier State Chronicles is an effort to digitize newspapers across all of Indiana. Of the state’s 92 counties, Hoosier State Chronicles contains newspapers from 54. This is not to say every county in our collection offers an equal number of newspapers or pages. The largest county in our collection by both number of newspapers and pages is easily Marion County, with 25 newspapers and over 43,000 issues. And the smallest? Posey County’s New-Harmony and Nashoba Gazette, or, Free Enquirer with one solitary issue. Does this mean that the counties with lower representation in Chronicles are less important? By no means! Limitations in access to historic newspapers, financial resources, or the quality of the papers have hindered our efforts to share titles from every area in the state. However, smaller or scattered issues may come to us as a part of a community effort to preserve some part of their history digitally. If even one newspaper represents a unique region, time-period, or subject, we absolutely want it to be a part of our collection.

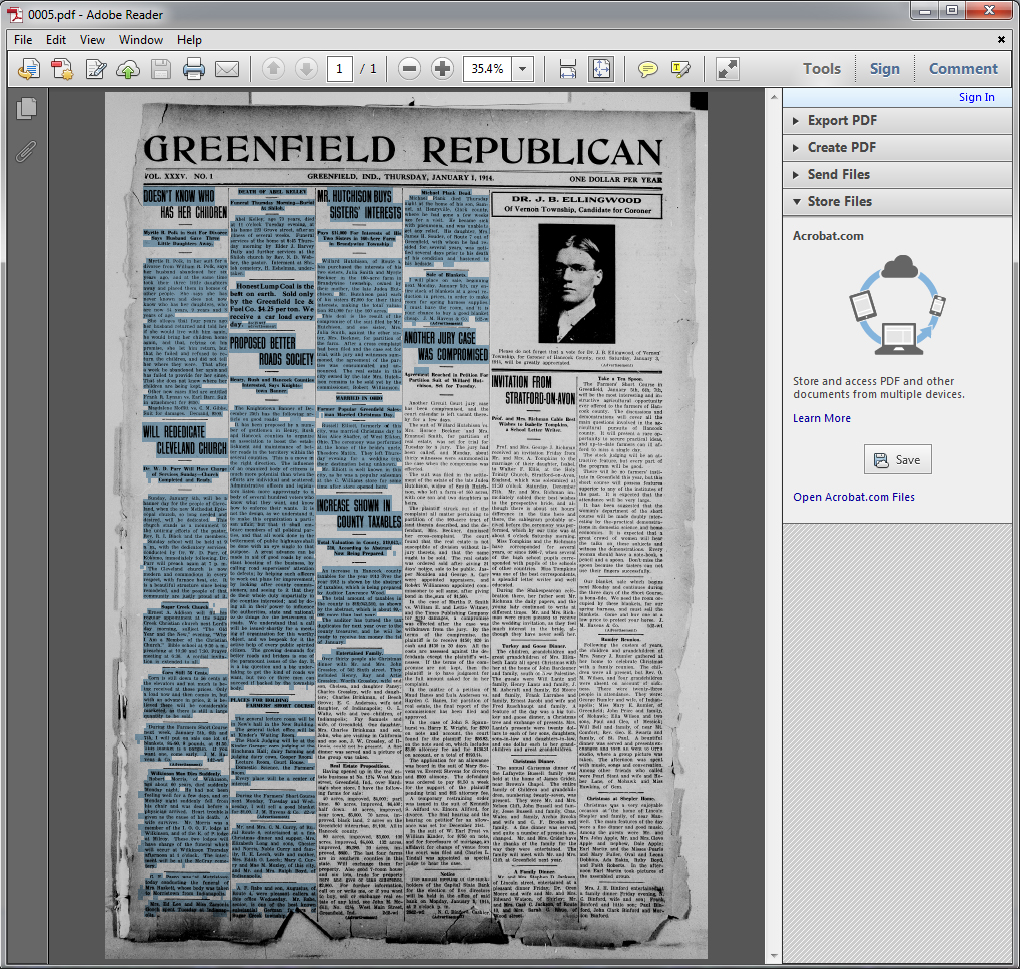

Our collection covers a broad range of eras in Indiana history. The oldest newspapers in our collection begin prior to statehood in 1804 with Vincennes’ Indiana Gazette, the earliest newspaper in the state, as well as its successor, the Western Sun. Two areas of strength for the collection are pre-Civil War and late 1800s newspapers, including early runs of the Indianapolis News, Indianapolis Journal, Indiana State Sentinel, Crawfordsville Daily Journal, and several in Terre Haute and Evansville. In the early 1900s, titles like the Richmond Palladium and Hammond Times provide terrific materials from eastern and northwest Indiana. Greencastle is also an area with multiple papers during these eras, particularly The Daily Banner and associated papers. The latest title in our collection is that of the Muncie Times in 2011, giving us 207 years of collections to share.

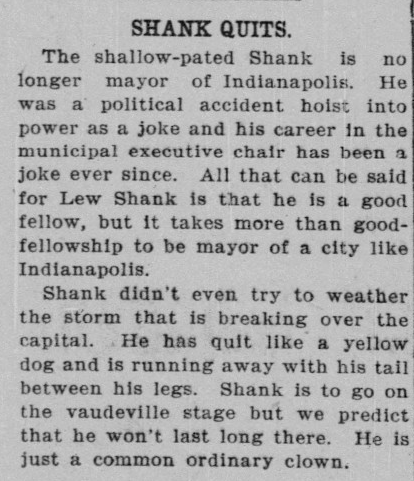

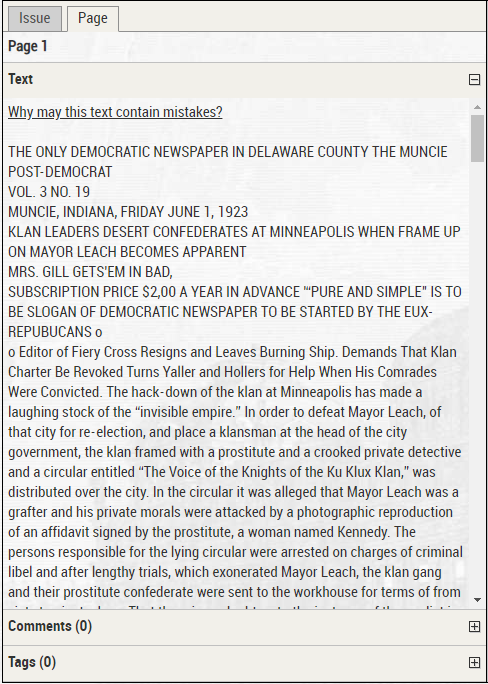

Another facet of our newspaper collection is the variety of materials in the collection. Politically, the collection displays contrasting perspectives, with newspapers supporting Republicans and Democrats, Whigs and Socialists. These feature both local and national news, often sharing the statewide perspectives of several parties. In regards to ethnic and racial diversity, we still have a long way to go. As mentioned previously, The Indianapolis Recorder, an African American newspaper, is the longest run in our collection. Additionally, the Evansville Argus and Muncie Times also share African American culture in Indiana throughout the late 30s-early 40s and the 1990s-early 2010s, respectively. Another long run of ethnic and cultural newspapers is the Jewish Post, later called The Indiana Jewish Post & Opinion, with issues from 1933 until 2005. Finally, the Indiana Tribüne has the distinction of being both the only predominantly-German newspaper and the only foreign language newspaper in Hoosier State Chronicles.

While every newspaper occasionally offers controversial news, Hoosier State Chronicles contains one newspaper that is especially difficult for modern readers. The Fiery Cross, a Ku Klux Klan newspaper out of Indianapolis, was published during the early 1920s. Despite its nature as an official newspaper of a hate group, it nevertheless provides insights to the rise of the organization during the 1920s, when they gained immense political power. It also highlights both the explicit and subtle racism and cultural biases of the Klan, particularly against African American, Jewish, Catholic, and immigrant individuals and groups.

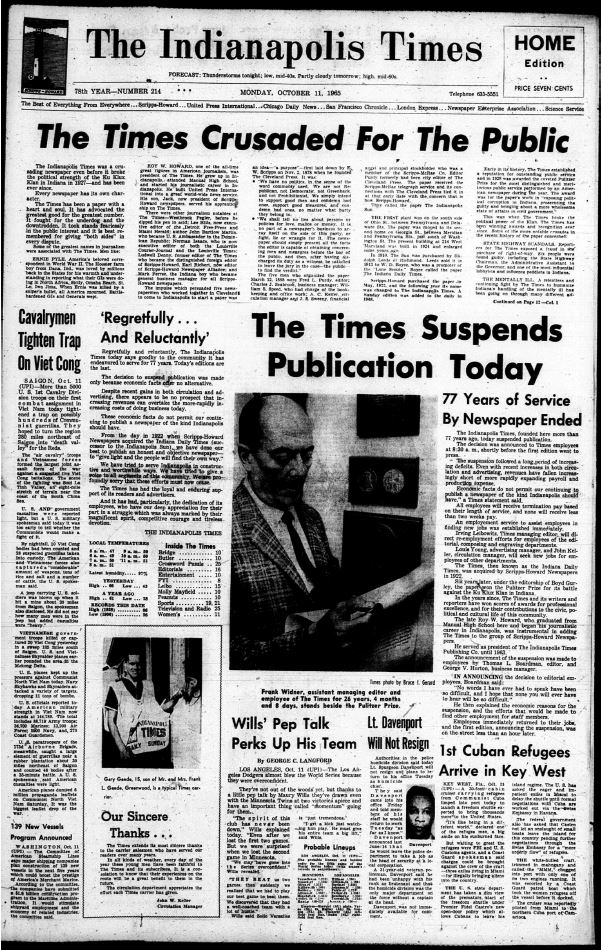

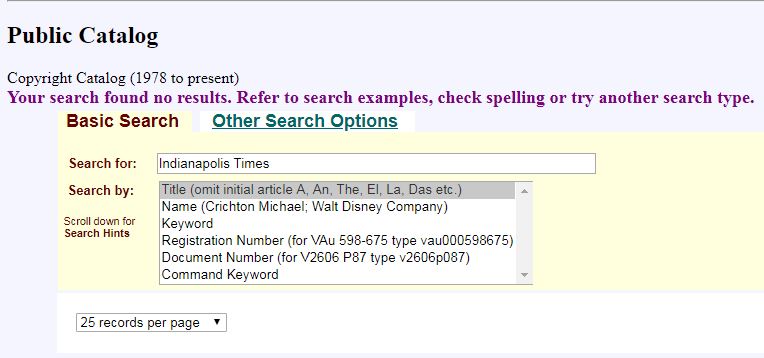

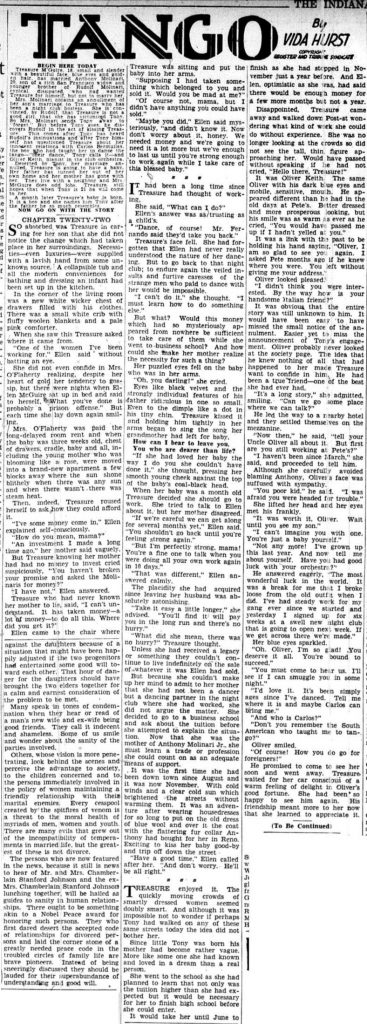

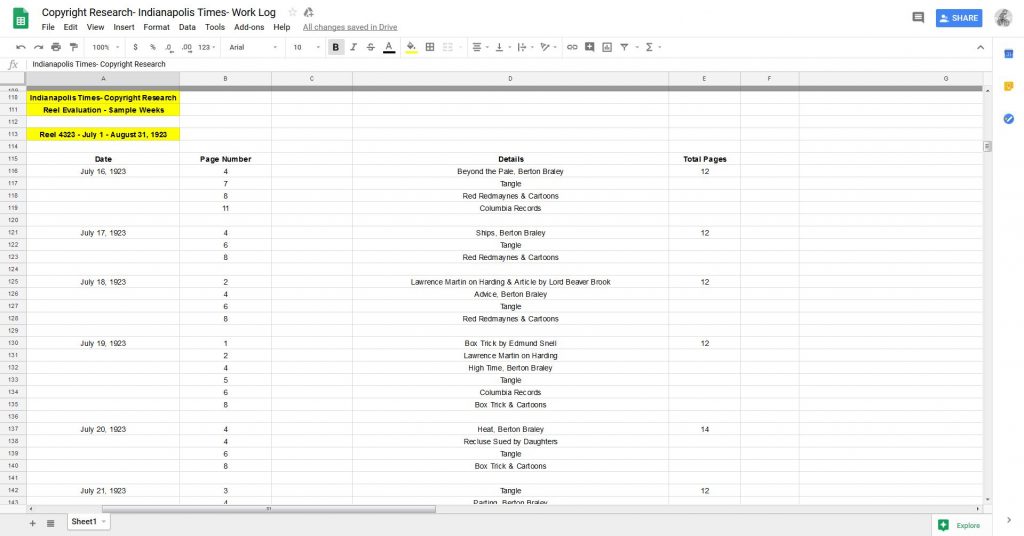

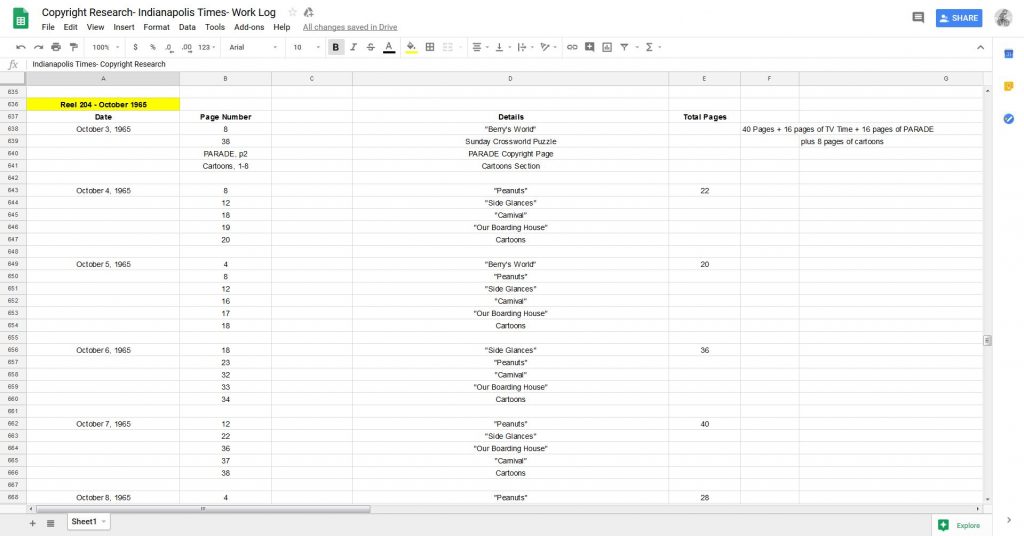

One newspaper not included in this list, but that is coming soon to Hoosier State Chronicles is the Indianapolis Times. The Times was an influential newspaper from the 1920s through the 1960s, whose exposure of the Ku Klux Klan’s influence on Indiana politics won them the Pulitzer Prize for journalism in 1928. They also covered other social issues like corruption in the prison system during the 1930s as well as inadequate care in the mental health-care system and corruption in state road projects in the 1950s.[iii] We are currently digitizing a large portion of the newspaper in two steps. First, 1922 through 1936 is being digitized through a NEH-funded partnership with the Library of Congress Chronicling America project, where these resources will be shared. Later issues between 1936 and the early 1950s are currently being digitized through a partnership with Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis and a grant from the Central Indiana Community Foundation. Once completed, close to thirty years of this daily newspaper will be available on Hoosier State Chronicles.

DIGITIZING PAPERS: SELECTION

Selecting newspapers can be challenging due to several factors. When assessing where our collection needs to grow, meeting community needs is first and foremost to the process. For the past eight years, Chronicling America and the Library of Congress assisted Hoosier State Chronicles through a NEH grant to digitize nearly fifty newspapers. Yet, sometimes the desire to digitize Indiana newspapers comes from communities. We assist them through the process of securing grants, selecting vendors, and creating appropriate digital resources that can be added to Hoosier State Chronicles. [iv]

Next comes determining what newspapers are readily available for scanning and processing. Oftentimes, this comes from the collection at the Indiana State Library, with over 3,000 newspapers from the state available on microfilm. Using microfilmed reels (1st/2nd generation negative master reels or 2nd generation positive service reels) makes processing faster and the materials easier to ship. However, some newspapers have limited availability due to scarcity of service copies or the lack of original master reels. Creating new-microfilm copies can be difficult due to few companies offering the service at a manageable cost.

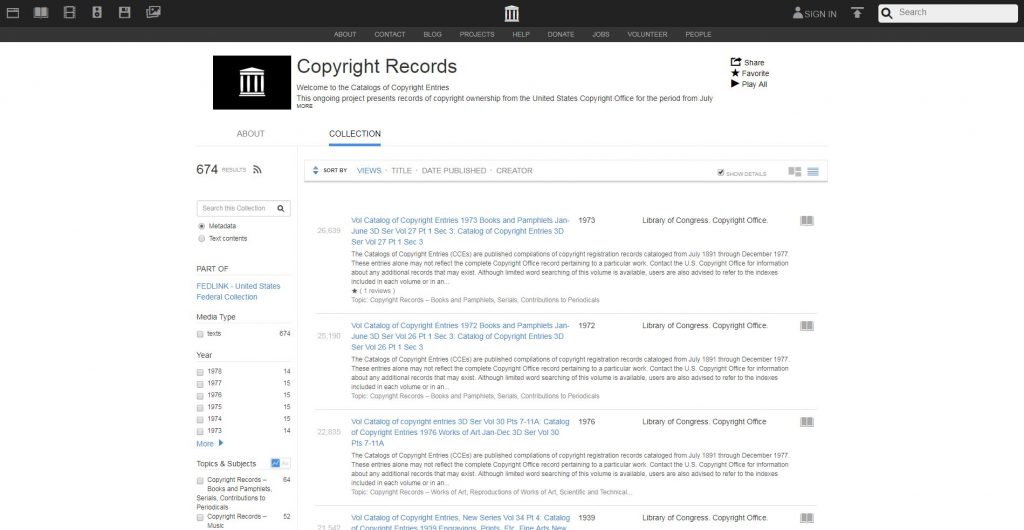

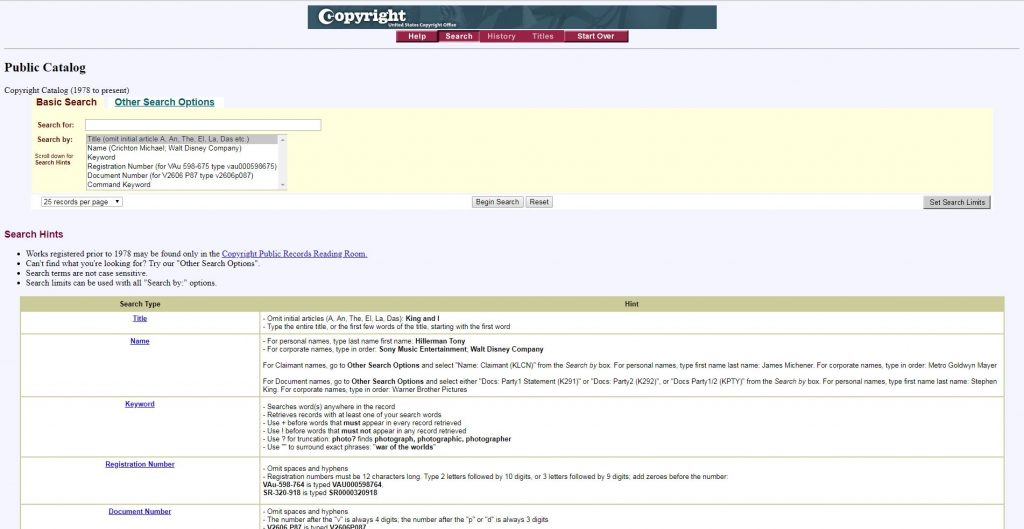

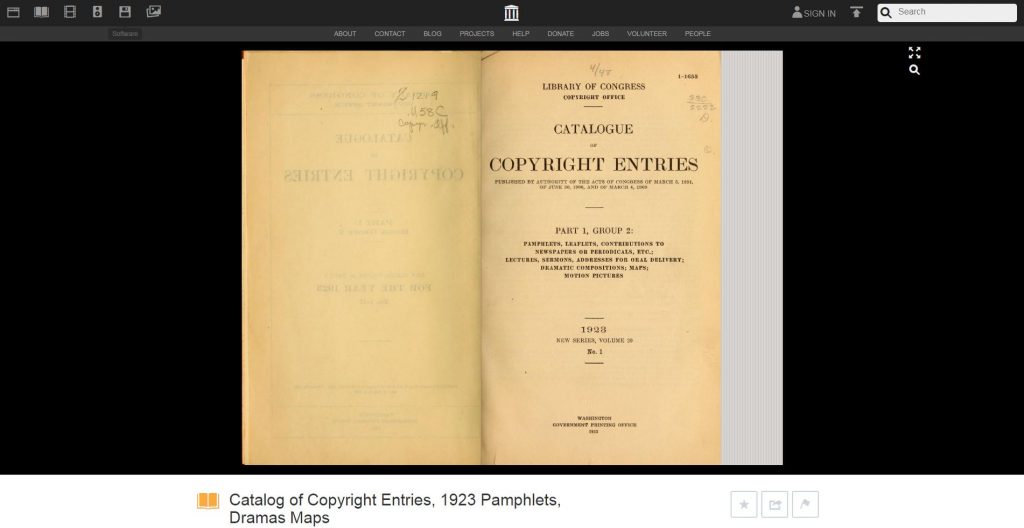

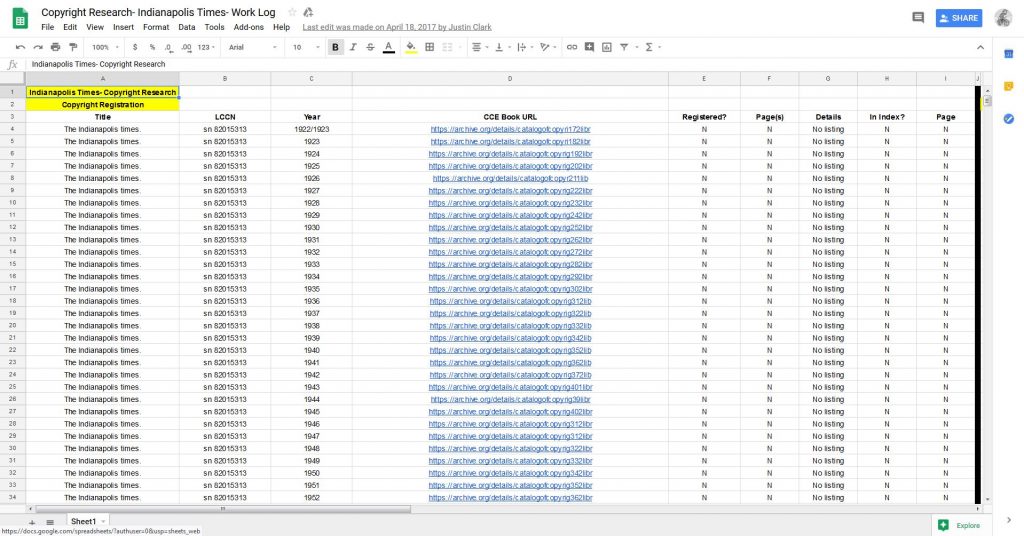

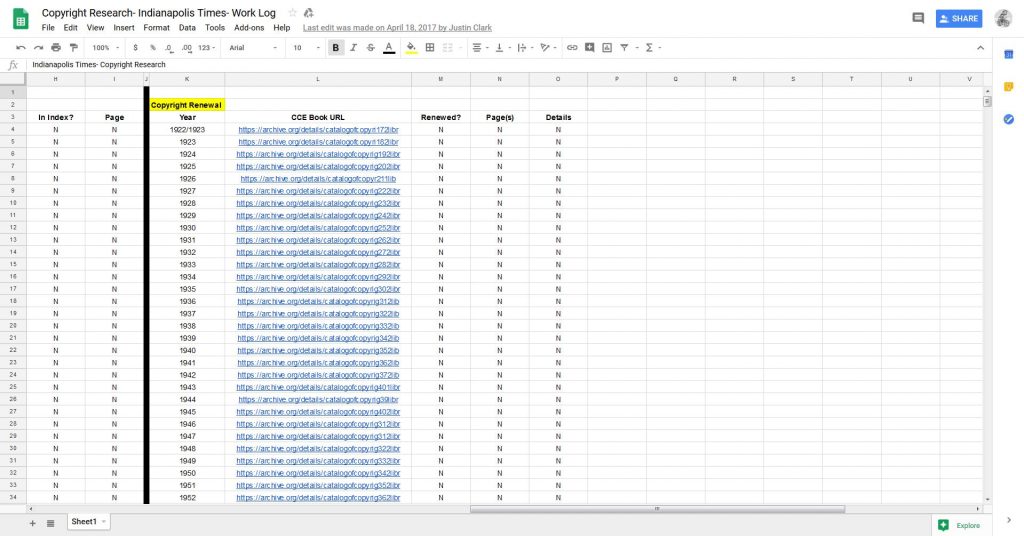

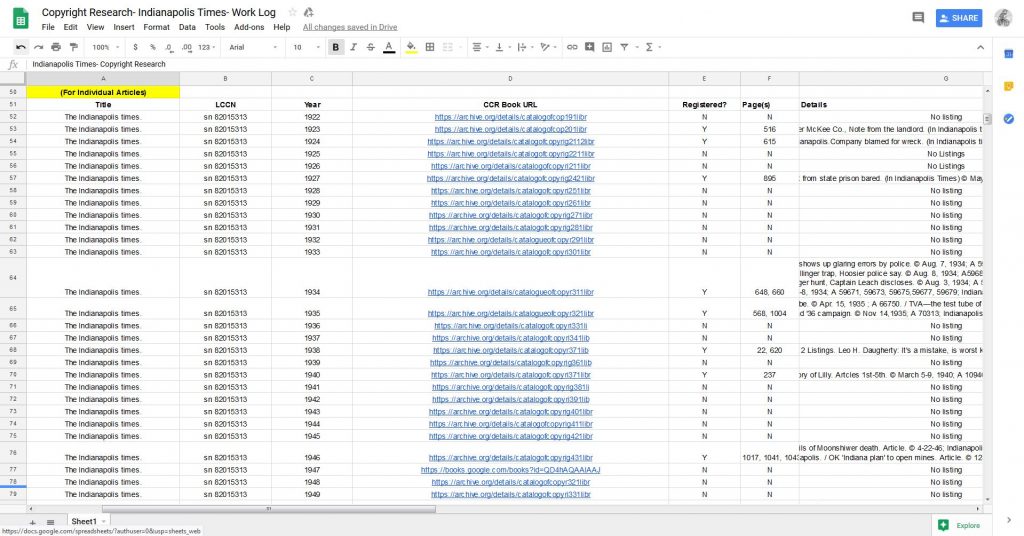

Though we may have microfilmed copies of newspapers in the State Library, it does not necessarily mean all are available for digitization. First and foremost, copyright restrictions limit which newspapers are candidates. Justin Clark, former Project Manager for Hoosier State Chronicles, wrote an extensive blog on the subject last year:

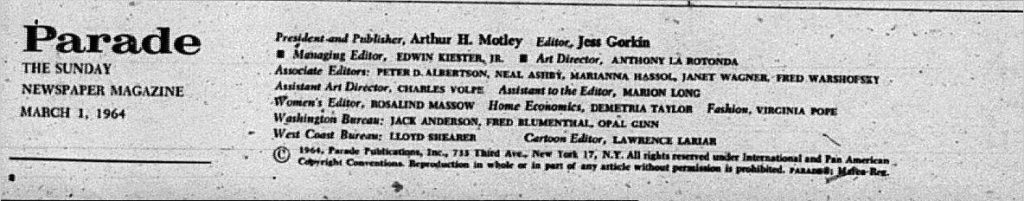

Have you ever wondered why the vast majority of NDNP’s content, and most digitized newspaper content, ends around 1923? It’s for a very simple reason: all works published in the United States before 1923 are in the public domain. No copyright research is necessary for this material; it’s free and clear for you to use. However, NDNP announced in 2016 that it has expanded its date range for newspaper titles, from 1836-1922 to 1690-1963. Thus, post-1923 works are in the public domain if a copyright claim was never filed from 1923 through 1977 or if the copyright was never renewed from 1923 through 1963.

This means that more recent newspapers may be wholly or partially unavailable due to copyright concerns, including advertisements or cartoons that could fall under intellectual property laws. That is why only three newspapers appear in our collection after 1971: the Indianapolis Recorder, the Jewish Post and Opinion, and the Muncie Times. These papers are available in Hoosier State Chronicles with the permission of the newspapers’ owners.

However, even newspapers that fall outside the copyright permissions may have other restrictions. Some newspapers have been sold or given to for-profit organizations for digitization or distribution, giving them exclusive access for digital distribution as long as the copyright is in place. Local communities who digitize through for-profit companies often gain access to the files in perpetuity, but at the detriment to those outside of the community who must pay for the digital version through a subscription. The cost of subscription, as well as restrictions on use, limits the average consumer from being able to view these for research or genealogy. Oftentimes, they are marketed as subscriptions to libraries or other organizations for popular use. Hoosier State Chronicles, Chronicling America, and other organizations involved with the NDNP offer newspapers in their collections for free to the public, giving alternatives to researchers, the public, and local communities.[v]

The last two concerns are intertwined: cost and time. Digitization can be a lengthy process, often taking months or years for larger collections. We will cover more in the next section, but the hours required to create a high-quality digital copy may be beyond the resources of smaller organizations. Additionally, the various costs involved with the acquisition, shipping, scanning, processing, and completing a run of newspapers may be daunting, but finding programs and grants to help relieve the burden is often a major part of starting such a program.

DIGITIZING NEWSPAPERS: PROCESSING

which makes the text clearer and more legible. Image Credit: Jill Black, ISL

Once a newspaper is selected and deemed eligible for digitization with no restrictions, the process of assessing the collection can begin. The initial process often involves cataloging each newspaper issue to verify its condition, making sure all pages are included and duplicates are noted, sorting to make sure all images are in order, notating any errors in the original print run, and marking flaws in the microfilm. This step can take months to complete in order to provide a thorough template for individuals digitizing the information and adding metadata (the data that organizes and makes the pages and newspapers searchable), as well as keeping meticulous records to assure everything leaving can be accounted for when it returns.

There are several potential options for the digitization process, and many of these depend on the size and number of reels for the newspaper. If the number of newspapers is small enough, or in a physical medium, it may be handled by a local or state agency like the Indiana State Library, who have on-site digital scanning capabilities. However, for larger runs of newspapers, outside companies will likely be required to handle both the digitization and metadata. While there are many options for vendors, the quality requirements, size of the order, and cost may dictate which vendor to go with.

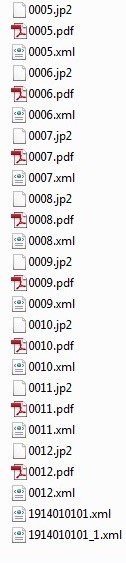

While the scale of work may vary, the system of digitizing large and small projects is very similar. The images are photographed by a high-quality digital scanner that scans the whole document, captures the fine details, and avoids capturing text bleeding through from the other side. From there, the images will be modified for readability, removing flaws and cropping out extraneous space. Files are usually saved in multiple formats for different uses: TIFF files are the highest quality and provide the archival copy, but are extremely large; JPG or JPG2 files provide usable quality copies at a lower resolution and size than TIFF files; and PDF files, which can vary in quality and size, can be downloaded by the public.

Metadata creation is distinctive from the digital scanning process, and while both systems need to work collaboratively, each could be performed by separate vendors. Metadata is the “data about your data” that gives images their descriptions, allows them to be easily sorted, and provides an order and structure to the files. If you are not familiar with metadata, think about how newspapers are numbered. Each issue of a newspaper has a volume number, an edition and a date that gives you a newspaper’s order of publication. Within each issue, page numbers also keep the newspaper in sequential order. All of these numbers are points of metadata that help us sort and organize the newspaper on a daily basis. They are also points that a computer system needs to know to organize the information when putting the files in order and allowing them to be searched and indexed. XML files act as the directory for metadata to be able to sort these files (see image on right.)

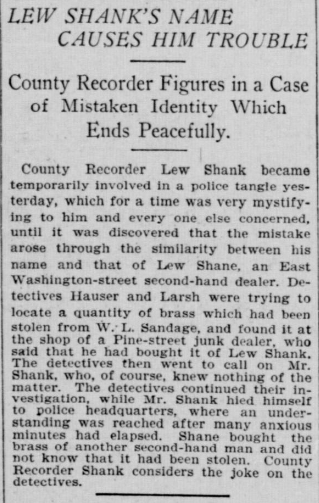

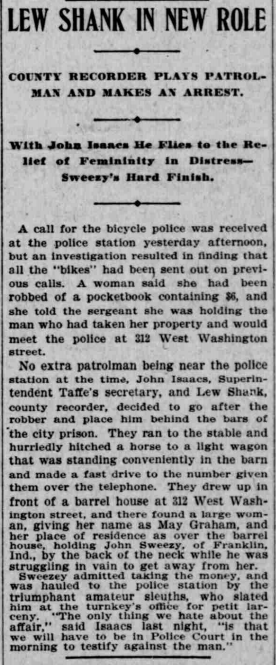

Another aspect of metadata for newspapers is making sure the text in the body of the newspaper is readable and searchable. Thankfully, one tool that makes this process easier is Optimal Character Recognition software, or OCR. OCR scans the printed pages in the images, translates them to text, and allows that text to be searched. Not only does this make the newspapers much easier to use, but it also adds a rough transcription of the pages (see image below).

Unfortunately, OCR is not perfect. The system works best when text is in standard fonts, in straight lines and columns, contains no illustrations, and is relatively the same size. As you may guess, this is rarely the case, particularly in modern or larger newspapers that contain advertisements, comics, or unusual text fonts. These can also be caused by the condition of the documents when they are scanned or the contrast of images. This occasionally results in gibberish translations or incorrect transcriptions from items the software recognizes as text (like an image). Still, like most technology, the systems improve as time goes on, and OCR is an essential part of making the information in newspapers more accessible.

recognized (blue highlighted areas) and displays distinctive paragraphs. Image credit: Jill Black, ISL

Without metadata, digital newspapers are nothing more than images. Metadata orders these images to replicate the experience of reading a newspaper while adding searchable information. The process of adding metadata requires a team with keen eyes to monitor the organization and placement of files during the digitization process, specialized technology that accurately recognizes text, and maintaining the image quality of every single newspaper.

DIGITIZING NEWSPAPERS: REVIEW AND UPLOADING

The process of creating a digital copy and adding layers of metadata can take the same amount of time as the initial review of the collection. Yet, after these are completed, the individual agencies who accept these digital copies must review as much as they can to assure that the highest standards are maintained. If this is done internally, the control process may be easily assured by spot checking the creation process. However, on a larger scale where vendors are utilized, checking to make sure each batch, or group, of digitized newspapers is correct as soon as they are available means you can request corrections before they return the microfilm.

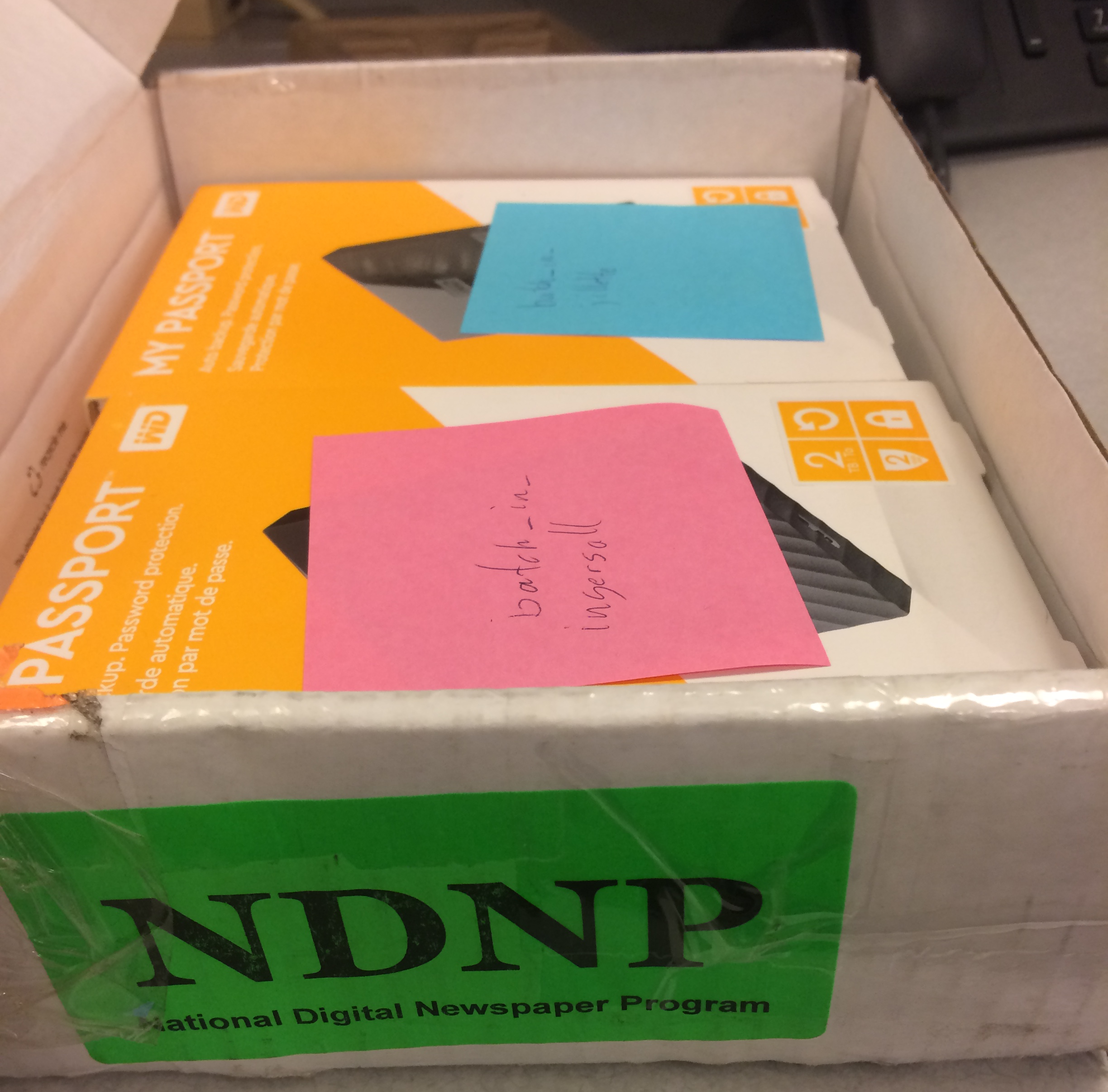

What kind of issues come up? Sometimes the scanning is not at the right quality or resolution, which necessitates a rescan. Maybe the dates, page numbers, or page orders are incorrect in the metadata and the information needs to be reorganized or edited. Occasionally, missing pages or issues that should be there need to be tracked down between the original film reels, the digitized files, and the metadata files. This is why it is important to review and revise everything in smaller groups, or batches, so the process of digitizing, adding metadata, and reviewing the completed material can take place simultaneously. Locally saved materials can be revised as you go, but larger-scale batches may require a remote digital transfer before you begin, or physically shipping off a hard drive.

Maintaining a digital collection of any kind, with thousands of individual newspapers saved in multiple formats, means investing in both external hard drives and backup drives. For example, our current digitization project with the Library of Congress contains portions of the Indianapolis Journal, The Daily Times, and the Indianapolis Times, which collectively require roughly eleven external hard drives and nearly seven terabytes of storage. To make sure everyone who needs these materials has them, we often have three copies: one on an external hard-drive that is shipped to the Library of Congress, one back-up copy on our local computer system for immediate access, and one copy maintained on our website. All three have associated costs, but it is good practice to maintain each for future use.

Finally, after all batches undergo quality review of their images and metadata, revisions are completed, and the batches are ready, they are sent to the appropriate locations. For the newspapers that are part of the Chronicling America project, they are sent to the Library of Congress in Washington D.C., where they undergo a second review to assure the files meet their specifications. Once everything is approved by all organizations, the files can finally be sent to either Chronicling America and/or Hoosier State Chronicles, where they are uploaded for public access.

CONCLUSION

Starting a new digital newspaper collection is often a large undertaking, but the established specifications, technologies, vendors, and programs throughout the United States show interested organizations that it can be done. If you are looking for how other organizations have handled this process, check out the list of organizations that have been awarded NDNP grants on the Library of Congress website: https://www.loc.gov/ndnp/awards/. Ultimately, the goal of digitization is making documents more accessible to the public, reducing damage to original sources, thus providing more contextual resources to our understanding of history.

A special thanks to Connie Rendfeld, Chandler Lighty, Justin Clark, Leigh Anne Johnson, and Jill Black in the creation of this document.

[i] Canepi, Ryder, Sitko, and Catherine Weng. “Microforms in Libraries and Archives” from Managing Microforms in the Digital Age, American Library Association, 2013. Accessed on July 16, 2018. http://www.ala.org/alcts/resources/collect/serials/microforms01

[ii] The program currently hosts newspapers from 46 states and Puerto Rico, and Indiana has 59 newspapers on the site as of today.

[iii] For more information on the Indianapolis Times, see notes from the Indiana Historical Bureau’s marker at: https://www.in.gov/history/markers/4115.htm

[iv] One source of funding is that of Library Services and Technology Act (LSTA) grants, which are funded by the Institute for Museum and Library Science (IMLS), of which the State of Indiana distributes funds. For more information on the availability of these grants, check out the State Library page at https://www.in.gov/library/lsta.htm, or contact Angela Fox at (317) 234-6550 or anfox@library.in.gov.

[v] The Indiana State Library and Hoosier State Chronicles have partnered with Newspapers.com in the past to digitize a large number of newspapers. In exchange for three years of exclusive access, over 1.5 million pages of Indiana newspapers are now digitized and accessible via the Indiana State Library’s Inspire website by following the links to Newspapers.com.